Ryerson University’s proof of vaccination system is expected to be put to the test in full force come January when tens of thousands of people are expected to return to campus.

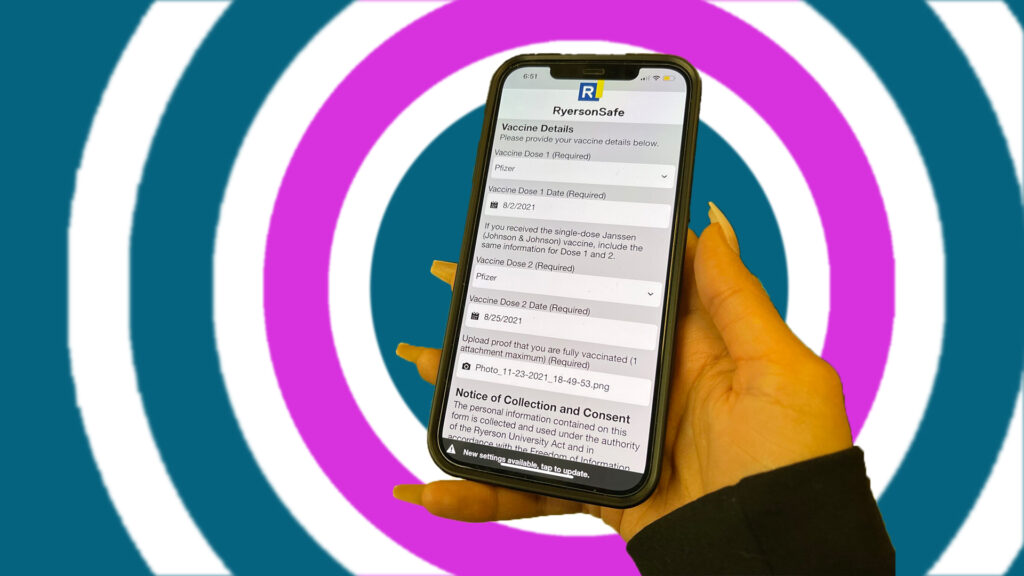

The system came into effect in September to comply with provincial mandates, and allows students, staff and faculty to submit their vaccination status through the RyersonSafe app.

Users can log into the app, select the type of vaccine they received, and the date of each dose.

They are then prompted to upload a photo of their government-issued receipt which specifies the person has received two valid doses.

Once a person submits proof, a green QR code with the word “approved” pops up, and a confirmation email is sent to their inbox.

LISTEN: What Ryerson isn’t telling us about the return to campus

The idea is that the QR code is used to quickly ascertain a person’s vaccination status on campus.

Want to go to a game? Show your code. Want to visit the library? Show your code. Want to go to the gym? Show your code.

However, a lengthy On The Record investigation has found the RyersonSafe app is programmed to greenlight every single submission — regardless of whether or not the person uploads actual proof of vaccination.

According to Ryerson president Mohamed Lachemi, there is an internal auditing process to check the validity of each submission.

But a request for an interview with internal audit services was denied by university spokesperson Jessica Leach. She said she couldn’t say more, citing confidentiality.

The RyersonSafe app creator, AppArmor, did not respond to a request for comment.

On The Record conducted an experiment with three people: two students and one staff member.

Each person was asked to upload false vaccine information along with a random photo to see if the RyersonSafe app’s software would recognize the difference.

In lieu of real proof, the three people uploaded a meme, a selfie, a view from a window, and a copy of one of the participant’s first-dose receipt.

Each time, Ryerson’s vaccine approval system instantly accepted the submissions and provided green QR codes allowing each participant to get on campus.

However, even once internal audit services became aware of the false information submitted by the three volunteers, it did not appear to take steps beyond emailing the staff member to implore them to give the correct information.

The staff member kept getting that greenlight each time they uploaded a false photo and fake vaccine dates.

Liam Ruddy, a fourth-year political science student who participated in the experiment, said he now feels that Ryerson’s system is operating in a way that is designed to “make it look as safe as possible, when in actual fact, it’s not.”

“I got that little green approved mark for literally uploading a meme,” he said. “That does not convince me in the slightest.”

Sydney Brasil, a graduating journalism student who also participated in the experiment, said it’s difficult to trust what now looks like a system that accepts submissions assumed to be made in good faith when providing vaccination records.

“If it is an honour system,” she wondered, “then how safe are we?”

If the information uploaded is never verified, it could potentially make people less inclined to follow the university’s pandemic policies, said Vass Bednar, executive director of the master of public policy program at McMaster University.

“The institution is doing as much as it can to ensure a safe environment,” she said, “But at the end of the day, if people are putting others at risk, they should be held accountable, not Ryerson.”

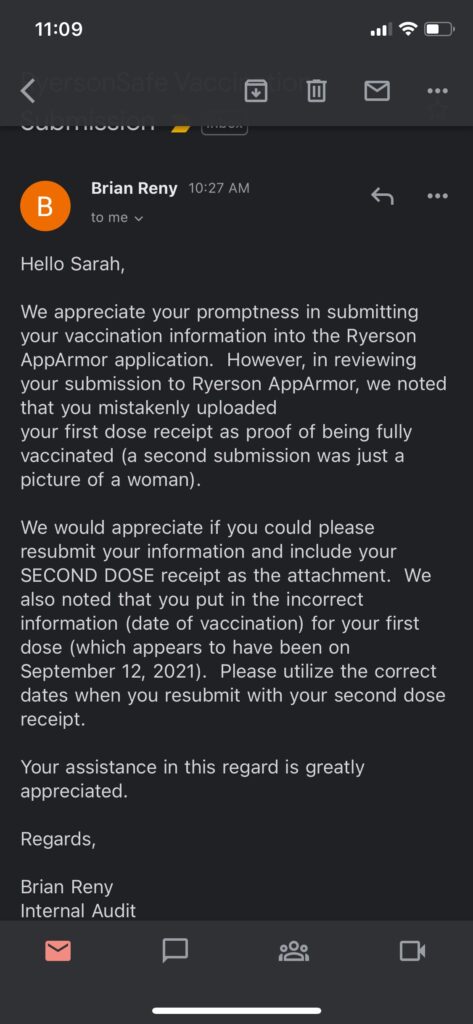

Twice, teaching assistant Sarah Samuel put the app to the test.

During both experiments, the app accepted her false submissions — a first-dose receipt with botched dates, then a selfie with fake dates and different vaccines — immediately, giving her a green QR code.

Four or five days after Samuel made her second false submission, Brian Reny, an employee in the university’s internal audit services office, followed up, asking her to resubmit actual proof of vaccination.

She did.

“I don’t know whether to trust this app or not,” Samuel told On The Record. “In a world where [everyone] is so misinformed right now, in terms of COVID, having more robust security, or internal audit tracking would alleviate stress.”

Submitting false proof of vaccination could lead to criminal charges and jail time.

Under the Reopening Ontario Act, forging false documents comes with a $750 fine, which is subject to change.

“These are the real consequences for this kind of behaviour,” said Constantine Karbaliotis, a privacy lawyer at nNovation LLP in Ottawa.

Karbaliotis said the repercussions students, staff or faculty could face if Ryerson caught them submitting false vaccine information depend on how serious the institution views the behaviour.

(Lachemi previously told On The Record that he doesn’t see “a need for us to police our community members.”)

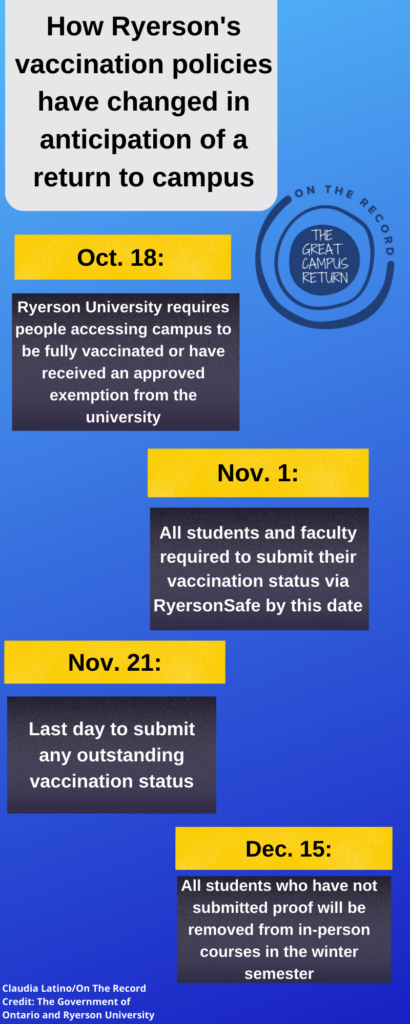

However, Ryerson has been tightening vaccine restrictions over the course of the semester.

In November it imposed limits on receiving winter term schedules for those who hadn’t shared their vaccination status.

The next step, according to the school, is to remove students who do not comply with the vaccine mandate from in-person classes.

Students risk losing access to key systems like RAMSS.

Students could also be disenrolled or suspended under Policy 61, the student code of non-academic conduct.

Faculty and staff have until Jan. 7, 2022 to be fully vaccinated or risk facing non-compliance measures.

In a statement, a university spokesperson said employees could be subject to “confidential” disciplinary action if they were found to have submitted false proof of vaccination.

On Oct. 17, Rebecca Thompson, a fourth-year urban sustainability student who previously uploaded real proof of vaccination, uploaded a photo of the street outside her window as new proof to the app.

She plugged in botched dates and vaccines and pressed “submit.”

Not even 30 seconds later, a green QR code popped up on her phone, and a confirmation email landed in her inbox. Thompson waited for an internal audit employee to follow up, but they did not.

“As an employer, or as an educational institution, or as a business establishment, you want to make sure that it’s a safe environment,” said Karbaliotis. “If you’re not actually enforcing a policy, or [holding] people’s feet to the fire about it, it’s very hard to discipline an employee for breaching it.”

According to Ryerson’s office of administration and operations, submissions to the RyersonSafe app are initially auto-approved to “ensure speed of approval and access for our large population of community members.”

In the app, everyone is required to legally attest to the accuracy of their submission, and there is an expectation and requirement of compliance, it said in a statement.

“If, during a review of documentation uploaded to RyersonSafe, there is concern about the validity of a submission, the affected community member is followed up with and non-compliance or false submissions are addressed accordingly,” the office said in a written statement.

“Health and safety during the COVID-19 pandemic is the individual and collective responsibility of all members of the university community.”

The university said its internal audit services can forcibly change a green QR code to red if a person it identifies as having submitted false information fails to provide real proof.

It also says the app provides a red QR code for people who indicate they are not fully vaccinated.

Throughout this fall semester, several students told On The Record that the university is rarely checking to see if they’ve submitted their proof of vaccination, or if they’ve completed the COVID-19 screening questionnaire each time they attend campus.

(The university said QR codes are checked at “certain campus locations before entry,” like the Mattamy Athletic Centre, the library, and others.)

Lachemi previously defended the university’s COVID-19 vaccination policy, saying there are no plans to have campus security check people’s proof of vaccination as they walk through the door.

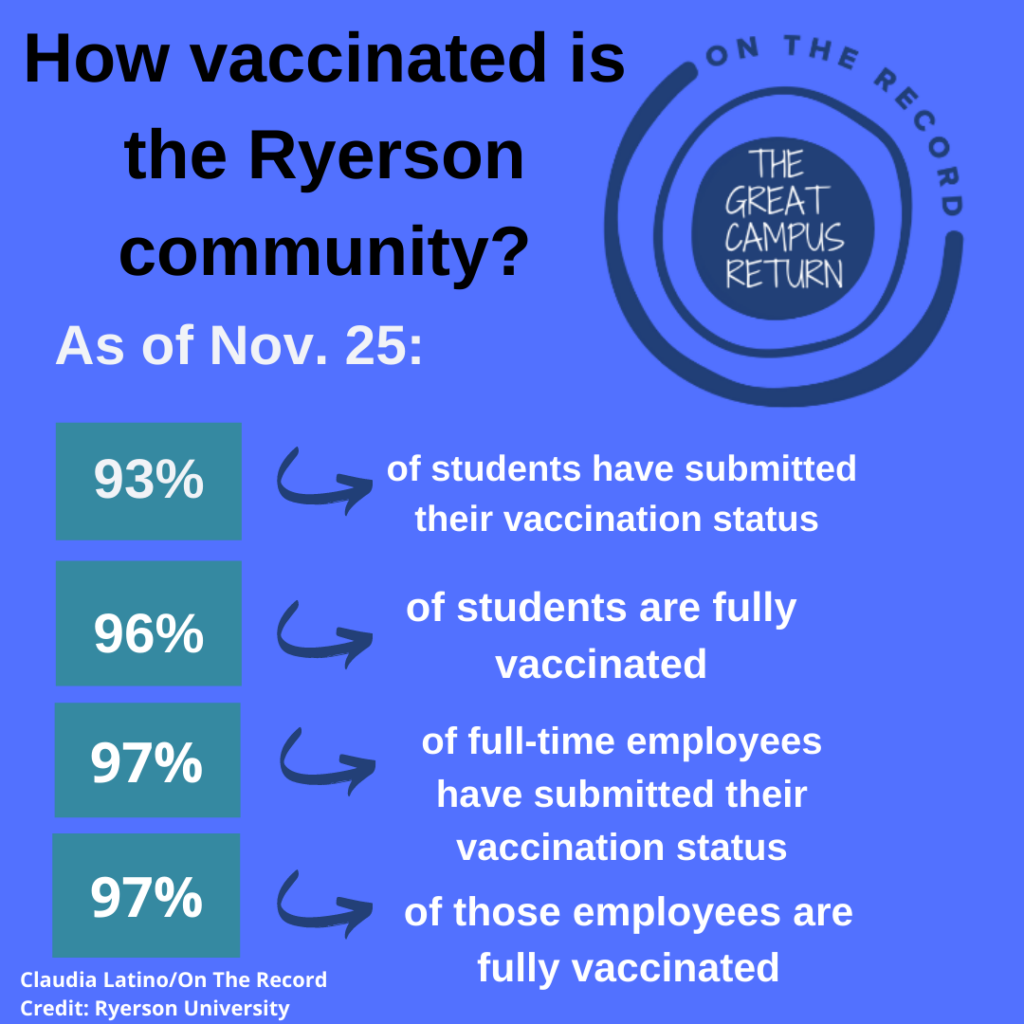

As of Nov. 25, 97 per cent of full-time employees have submitted their vaccination status. Of those, 97 per cent indicated they are fully vaccinated.

For part-time employees, 84 per cent have confirmed their vaccination status, and 99 per cent say they are fully vaccinated.

The university said the majority of employees who have not yet provided their vaccination status have contracts that expire on or before the end of 2021.

The rest are either pursuing full vaccination or are not working on campus as a condition of their employment.

As for the full-time student population, 93 per cent have submitted their proof of vaccination, with 96 per cent of them indicating they are fully vaccinated.

The university has repeatedly declined requests to share the number of medical exemption requests that have been made and approved, citing privacy and confidentiality reasons.

Lachemi previously said it is “a small number.”

Lachemi said the university is aware of who is fully vaccinated or not based on a list of students attending in-person classes.

However, he wouldn’t say whether the university solely relies on the RyersonSafe app data to curate that list.

If it does, that could mean that not everyone the university thinks is vaccinated, actually is.

“I got that little green approved mark for literally uploading a meme. That does not convince me in the slightest.”

Liam Ruddy, Ryerson student

Ryerson told On The Record it uses the RyersonSafe app to track the status of everyone’s COVID-19 vaccination record so it can follow up with those who are not in compliance.

Thompson, who uploaded the view from her home as “proof,” now counts herself among those feeling unsafe.

After participating in the experiment, she’s skeptical of whether the university’s COVID-19 policies are actually working.

“It definitely makes me question everyone else’s vaccination status … Literally anyone can say they’ve been vaccinated [even] if they haven’t with this system, which is a little nerve-racking because people could just be lying, going on campus without their vaccines,” she said. “The whole reason we have this system is to prevent that. So if the system is broken, or not doing its job, then what’s the point of even having it?”

Ruddy said he was “insulted and disappointed” when he saw the system accepted his false information.

It makes him feel like the university’s policies give its community members a false sense of hope ahead of January’s in-person return, he said.

It’s possible that the RyersonSafe app’s automatic greenlight in cases where a person falsely submits proof of vaccination is the result of a failure to thoroughly test parts of the app during product development, said Lakshmi Baskaran, vice-president of engineering for SEDNA Systems.

“When you build the software, you [must] ensure that the software is thoroughly tested, especially in a product or an app like this where the product or an app deals with a user’s personal identification information,” Baskaran said. “The software should be tested to ensure that there are no loopholes.”

She suggested the university subject the RyersonSafe app to more negative test cases to close the loopholes and make sure the app does not approve fake vaccine information and photos.

For example, Baskaran explained, a pending process could be put in place to give the university time to review each submission.

Then the school could ensure it is only approving vaccine certificates once they are verified.

“We as software developers have to ensure that the products we build are safe, secure and reliable,” she said, calling it an “ethical obligation.”

The university did not respond to a question about whether it would consider implementing a pending process that does not automatically greenlight people who submit proof of vaccination even if the “proof” isn’t real.

The easy fix, Karbaliotis said, is to use the province’s certificate.

That certificate also operates a QR code system. Businesses can use it, but they aren’t mandated to. Karbaliotis wonders if that might change.

“It’s tied to your name,” he said, so it will “prevent the editing of PDFs approach, which is allowing this kind of craziness to go on.”

READ THE FULL SERIES: The great campus return?

Elena is an award-winning investigative journalist for the Investigative Journalism Foundation. She is the former editor-in-chief for On The Record and has done multimedia reporting for several news organizations, including the Canadian Press, Globe and Mail, Timmins Daily Press, North Bay Nugget, 680 NEWS, and Pressed News. Elena has also written freelance pieces for Maclean’s, the Welland Tribune, Niagara Independent and The Eyeopener. She holds a Master of Journalism degree from Toronto Metropolitan University and an Honours Bachelor of Journalism degree from Humber College Lakeshore. Elena is also a bilingual, self-published author who is passionate about public interest journalism and press freedom.