Listen to the full audio here:

A new tanned hide exhibit opened on Monday at TMU that explains the science behind the Cree tradition, and is open to the public all week. The man behind it is Caleb Wesley, a member of Moose Cree First Nation, some 900 kilometres north of Toronto.

Wesley said he wants, “to bring both science literacy and Indigenous education together,” in the exhibit showcasing tanned hides he created between 2019-2020 as part of a “revitalization of those practices in contemporary times.”

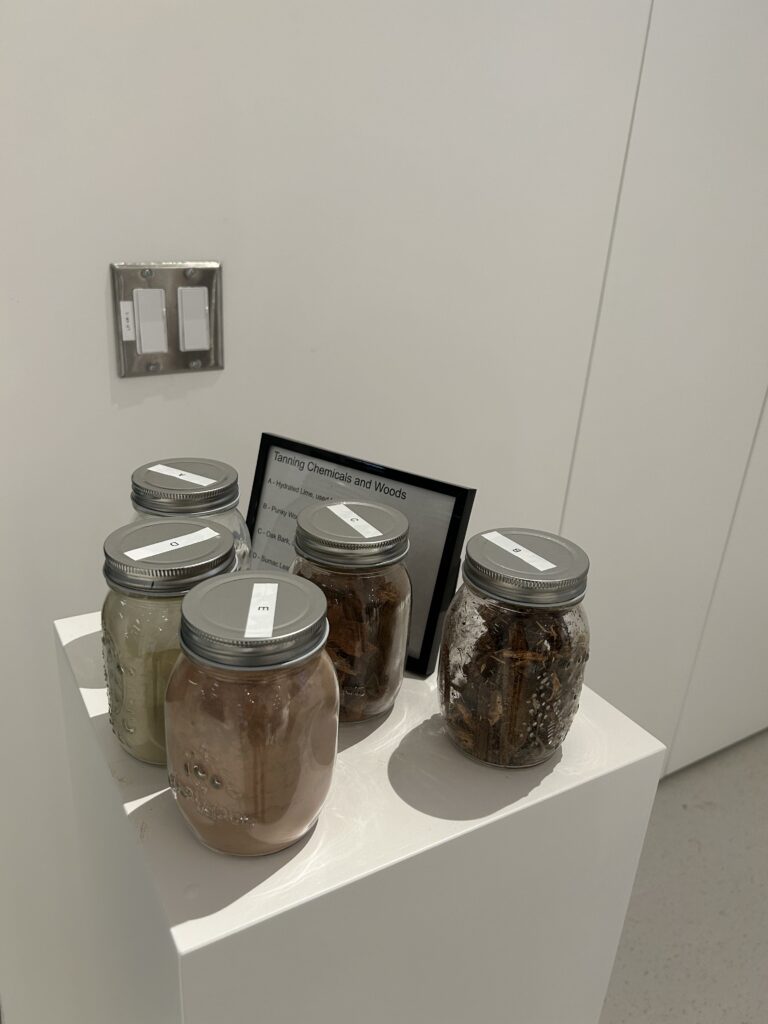

Between the pearl-white walls, a projected film is played in the background documenting the process, while tanned deer hides and frames hang nearby. An array of fragrant spices imported from North Africa used for the tanning process are on display.

Wesley said the practice was discontinued in his family after his great grandparents’ generation due to changing economic situations in his community, making hide tanning economically difficult.

“I think it’s really important for not only cultural continuity, but connecting us with our ancestors,” said Wesley.

The process, as Wesley explains it, begins by “removing the grain”: soaking the hide in a solution of wood, ash or lime scale and then scraping the hair off the upper layer of skin. The hide is then soaked overnight to remove the lime scale and wring dried of any residual moisture. It is then framed, softened, stretched, dried and smoked. While only deer hides are on display, other animals harvested for hides traditionally include fish, moose, elk, foxes, coyotes, and wolves.

“I don’t think that we get to see a lot of Indigenous science-based activities or educational opportunities,” said Kid Naary Branco, a biology student at TMU and the event coordinator.

“[I’m] hoping more people come to our gallery, learn about hide tanning and recognize the connection to Indigenous culture,” said Branco.

“I think it’s very interesting … how the [Cree] use science for their traditions… [and] to see how different solutions can help preserve things that have been here for hundreds of years,” says Parmida Sanaei, a fourth-year psychology and biomedical student visiting the exhibit.

While Wesley says concerns by animal rights activists regarding the practice are “very valid,” he reiterates that no part of the animal goes to waste.

“Pre-contact… we learned how to harvest what we needed to survive, but we were also dependent on the continuity of those animals,” he said.

“I don’t think it is cultural appropriation for a non-Indigenous person to engage in hide tanning,” Wesley said, as similar practices exist in Japan, China, Scandinavia, North Africa, and the Middle East. According to Wesley, it’s the intention that matters.

“I think what’s important is for folks to think about what’s their intention with hide tanning and if their intention is good,” Wesley said. He cautions against, “using it to pretend to be Indigenous, or try to intentionally appropriate that art and advertising themselves as an Indigenous knowledge holder.”

“That”, he says, is when it “becomes cultural appropriation.”

I am an up-and-coming journalist, with a particular interest in investigative journalism. I have published for various publications, including the UofT Varsity Newspaper and TalentEgg. This fall, I will be reporting for OTR.