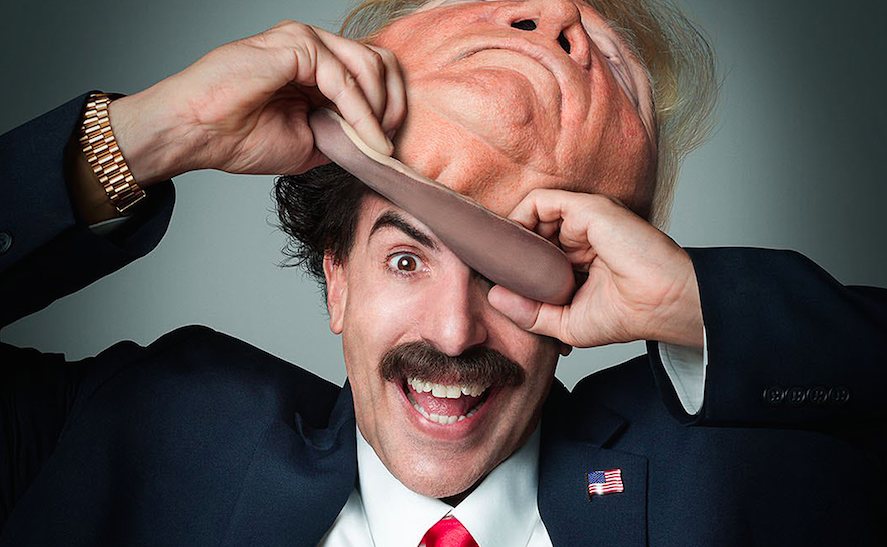

‘Borat Subsequent Moviefilm’ reveals the dark side of American conservatism, but will it change voters’ minds?

“Journalists! What we gonna’ do? Chop them up like the Saudis do!”

In the movie Borat Subsequent Moviefilm: Delivery of Prodigious Bribe to American Regime for Make Benefit Once Glorious Nation of Kazakhstan, Sacha Baron Cohen sings these words at an anti-lockdown rally in June 2020, while he’s disguised as Borat, who’s disguised as an American farmer. People in the crowd need no encouragement to sing the words back to him, cheering and shouting. The movie is full of jaw-dropping moments like this one, that reveal how casual racism and fake news have permeated the minds of many Americans.

The new Borat film, a sequel to Cohen’s 2006 movie, has dominated the news since it was released. Even in the days before its release, President Donald Trump’s personal attorney Rudy Giuliani tweeted to share his disdain. Trump himself referred to Cohen as “phony” and a “creep.”

The U.S. election is Nov. 3, but it’s been all over the news and the media for months, even years.

“The day after Trump took office in January 2017, he started campaigning for 2020. We have our six- to eight-week elections (in Canada), and theirs go on and on,” says Marion Coomey, a professor at Ryerson University. She’s a self-proclaimed news junkie with an extensive background as a TV reporter and producer with CBC News.

Voters have been all-consumed in the divisive, hectic politics of the American election. When movies like Borat are released, politicians do cameos on shows and other movies, and are played by comedians on Saturday Night Live. The lines between American politics and entertainment have been blurred and the 2020 U.S. election has been a bizarre journey of scandals and fake news, even featuring an insect guest star.

Canada’s elections are far less of a spectacle.

“We usually have higher voter turnout than the U.S., so there is less need for parties to stage spectacles to attract the attention of voters,” says Wendy Burton, a professor at Ryerson University. Before coming to Ryerson, Burton had experience as a journalist, a political campaign manager and as the first female president of the Canadian Association of Journalists.

“It’s certainly not the same in Canada,” says Coomey. “We’re a lot more waffly. The difference between New Democrats, Liberals and Conservatives is far less of a difference than between Democrats and Republicans.”

The two-party political system in the U.S. makes for a more contentious and competitive atmosphere during the election. The country is split between red and blue, and there’s very little room for any blending of the two. Politicians hurl insults at each other, unearth family secrets and make up lies. And with America’s obsession with fame, celebrity and reality television, it’s no wonder that watching a presidential debate is as entertaining as watching an episode of Dr. Phil or The Maury Povich Show.

“The entire country is one big reality show, and the presidency is at the centre of it,” says Coomey.

The other side of America’s fame obsession is the idea of “American exceptionalism,” or being taught that the U.S. is the best and most important country in the world. The world continues to turn, but Americans may not realize their election’s media coverage has a tendency to overcompensate.

Trump himself is a master of blurring politics and entertainment. Trampling over Ronald Reagan’s footsteps as the first “actor” president, Trump has carried out his campaigns and his presidency much like his presence on The Apprentice as a tough, merciless mogul. He’s successfully branded himself and branded his opponents to the point where the entire world has heard references to Hillary Clinton as “Crooked Hillary” or to Joe Biden as “Sleepy Joe.” He thrives on media attention and uses Twitter to effectively keep the focus on him and refresh the media’s repertoire of Trump headlines.

The focus is rarely on policy. Americans are more interested in politicians’ history, their family and their lifestyle.

“Most people in the U.S. know very little about their system of government,” says Burton. “A deeper dive into policies would be more productive but would probably not get very high ratings.”

But can politics as entertainment actually sway the minds of American voters?

Trump was accused of sexual assault by at least 26 women, he mocked a reporter with a physical disability, he bragged about groping women without consent and he said that Mexican immigrants are rapists bringing drugs into the U.S., all in the public sphere. It’s clear that Trump voters are not easily swayed by the media spectacles made out of Trump’s missteps.

“If none of those things are changing anybody’s mind, I don’t think Borat will,” says Coomey.

The many degrees of separation between red and blue mean that many Americans have long since known who they plan on voting for, and those who are watching the Borat sequel are likely not doing so for political inspiration.

But the entertainment industry can be effective for those who are new voters, or who weren’t planning to vote at all.

“They’re gambling on it kicking some people in the butts and getting them to the voting booths,” says Coomey. “Young people typically feel disenfranchised, they don’t feel they’re being spoken to. There can be some influence from younger celebrities convincing somebody to vote.”

The final scene of the Borat sequel closes with a demand to all who are watching: “Now vote or you will be execute.” And while no one will actually be executed for not voting in the 2020 U.S. election, lives are at stake.

Perhaps the most dangerous part about the U.S. election as it appears as an entertainment industry, is the notion that it is entertainment and nothing more. The importance of this election goes beyond knowing the contents of Hunter Biden’s laptop or Trump’s tax returns, and the Borat sequel, as ridiculous as it is, may be the only way to cut through these headlines.