How the intersection of race and mental illness stigmatizes Black Canadians

When I first spoke to my doctor about my depression in the summer of 2015, he asked me point blank if I ever attempted suicide. I lied. That was enough for him to ignore the symptoms I had told him about and declare I did not have clinical depression.

It would be another year before I opened up to my sister, giving her the full story. I saw through her awkward silence. Despite our six-year age gap, we were close — so close people always referred to us as “the girls.” So, how was it that I hid such a dark secret from her and for so long?

I knew her well enough to know — when I first told her — that she was holding back from truly taking in what I had confessed. She held her composure well, but I detected a few changes in her pitch when she inquired more about it.

“Why didn’t you tell the doctor?” was one of the first questions she asked me.

It was a question I didn’t know how to answer, at least not then. And in truth, I honestly can’t recall the answer I gave her. What I was certain of, though, was that I would not be looked at the same if I uttered the word “suicide” out loud.

It could result in me being treated differently when I entered the workforce, attended a class or even just socialized. Worse, people might see me differently not only because I struggle with mental health, but because I do so while being Black.

It was clear to me — even in that first conversation with my sister — that I would not only have to face stigmatization based solely on my race, but also based on my mental health.

Many Black Canadians, like myself, who suffer from poor mental health are faced with a dilemma known as a double stigma. In essence, people with an already stigmatized identity face even more complications and difficult life circumstances when dealing with another stigmatizing identity. Experiencing anti-Black racism and systemic injustice impacts the decisions Black Canadians make to seek help for mental health, which is already highly stigmatized in Canada.

Aside from community-based stigma, institutional stigma also has a role to play in this suspicion, according to Kelly K. Anderson, an epidemiologist who researches psychotic disorders at Western University.

“If you have a Black man who’s agitated, his clinical presentation is likely to be perceived differently from a white man who’s agitated,” Anderson told me.

What makes African and Caribbean communities in Canada vulnerable to mental illness, according to a report in the Toronto Star, are factors such as “poorer education and housing, unemployment, poverty and criminalization.”

“When we take a look at the Black community, you have people who are struggling with poverty and racism,” said Jennifer Cassimy, manager for mental health support services at Caribbean African Canadian Social Services (CAFCAN) in Toronto.

A 2019 report by the Mental Health Commission of Canada refers to these factors as social determinants of health. One of these determinants — education — directly interlinks with the stigmatization of mental health within these communities.

“A lot of people just think mental health is schizophrenia. Like, that’s it. But we don’t talk about anxiety, depression, personality disorders, bipolar disorder — we’re just not properly educated,” said mental health advocate and filmmaker Stacy-Ann Buchanan. She is known for producing The Blind Stigma, a first of its kind documentary to explore mental illness in the Black Canadian community.

The lack of education on mental illness makes it difficult for families to understand the underlying conditions, as was the case with Marie Remy, executive director of Fabiola’s Addiction and Mental Health Awareness & Support Foundation (FAMHAS Foundation) in Ottawa.

Her organization is named after her late sister who struggled with addiction and mental health problems, something she said her family “didn’t know much about.”

“I tried convincing her to get help and she tried multiple times… it didn’t help because that was not the true problem,” said Remy, noting this was because she and her family did not understand that Fabiola’s addiction was a byproduct of her battle with depression.

A study from 2015 found that cultural beliefs tend to dictate responses to dealing with mental disorders.

That finding is in keeping with a paper from Canadian social scientist Ingrid Waldon, who found, “Many African peoples on the continent and African Caribbean peoples in Canada perceive ‘mental illness’ as being caused by external sources (such as evil spirits or gods) as punishment for wrongful deeds.”

That matches mental health advocate Imadé Nibokun’s experience as an African-American growing up in a religious household.

“It was very much a ‘pray away’ atmosphere,” said Nibokun, the creator of Depressed While Black, a blog that serves as a community for African-Americans who need mental health support.

“You just got to use your willpower and your spirituality to get out.”

Going into 2010, I realized nothing in my life was as I expected or wanted for myself. At 16 years old, I had been living in Barcelona with my mother, sister and stepfather for two years.

Whenever my sister and I would leave our apartment to go for a walk around our area, we would be faced with microaggressions or cartoonish, 1960s-style racism. The kids our age would stare at us or make faces. Then there were those awkward bus rides where we would sit beside someone and they would shuffle in their seats to avoid having their body parts touch ours.

Though our mother decided to have us home-schooled through an online, private school, I sometimes believed it was a blessing that spared us from more potential racism. But home-schooling came with its dark sides, too. It was lonely at best and crushing at worst. I felt so burdened by the responsibility of managing my time alone while studying independently that I fell behind — the beginning of my first depressive episodes.

Complications also came from within the household. My stepfather was controlling and often quarreled with my mother over the smallest things. If she disagreed with him over something, he saw it as “disrespect.” While my sister often stood up to him, I tended to walk on eggshells because I hated conflict. But seeing my younger sister acting braver than me caused me to question my self-worth. Was I weak for not standing up for myself?

At the same time, my mother was trying so hard to hold everything together that it became harder for her to grasp the reality of our situation. We lived through harsh circumstances in Spain, but they were nothing compared to the rough life my mother had growing up — ones she swore to shield my sister and I from. But that made it difficult for her to understand where I was coming from or how I could be depressed.

I internalized this. I told myself that nobody else in the house was crying over their lives the way I was. I questioned my strength, without realizing how much of a toll being “the strong one” was taking on my own sister. Years later, she would reveal to me how many times her feelings were disregarded simply because she looked “strong enough” to handle it.

This association of strength with Blackness is a colossal hindrance to Black Canadians seeking help for mental health problems.

“Part of that is coming out of slavery mentality,” said Cassimy. “Because even with the Tuskegee project they had, and with the whole history with slavery, it was perceived that Black people don’t have the same feelings as white people.”

The Tuskegee project was an unethical, American experiment conducted on 600 Black men with syphilis in Tuskegee, Ala. The men were told they would be examined for health problems like stomach aches and would be offered treatment and care. But they were misled, as the study was actually part of a secret experiment examining the effects of syphilis. The promise to get treatment was false, which led to many of these men dying at the hands of researchers. Black men are taught to be strong and that often means keeping their feelings and experiences to themselves, according to The Blind Stigma. Black women, on the other hand, have to hold everything together and be strong for their families and their men.

Perfectionism is an important direct cause of my depression and anti-Black racism was a major contributing factor. But racism was hard to talk about among my peers, let alone a doctor.

Any time I returned to Canada during the summer and people asked my sister and I about Barcelona, we always had something negative to say about the racism we faced there. But our experiences were always met with some form of “but there are racist people everywhere” or silence among our white peers. From our Black peers, the reaction was not that much different. It was just racism and we were expected to just deal with it.

It wasn’t until 2017 when I came back to Toronto to live that I was finally able to seek counselling services. I quickly applied for university as soon as I learned of Ryerson’s counselling services for students. I was quick to book a consultation.

I talked about my experiences with racism, my perfectionism, my depressive state and the difficulties I faced dealing with all of that on top of being a mature, first-year student. I felt like it was the first time I poured my heart out to somebody who had the power to get me the help I needed.

The response to the consultation was to put me on a wait-list, which came as a surprise to me.

The worst part of that situation was how I responded to it. I told myself there were probably students dealing with much worse than me and that, maybe, my issues were not as grave as I believed them to be after all. I told myself that catastrophic events would have to occur before I could get the help I needed — and they did.

On Nov. 11, 2017, I had my first seizure. It took until my second seizure on Jan. 23, 2018 before doctors confirmed my diagnosis: an idiopathic seizure condition that could lead to seizures because of sleep deprivation or stress.

The student counselling services saw this as a turning point, a pivotal moment in my life where this new-found condition would cause me mental stress, so they took me off the wait-list. And in February 2018, I attended my first counselling sessions.

But by that point, my struggles with mental health were already long and trying. I had been crying for help for eight years.

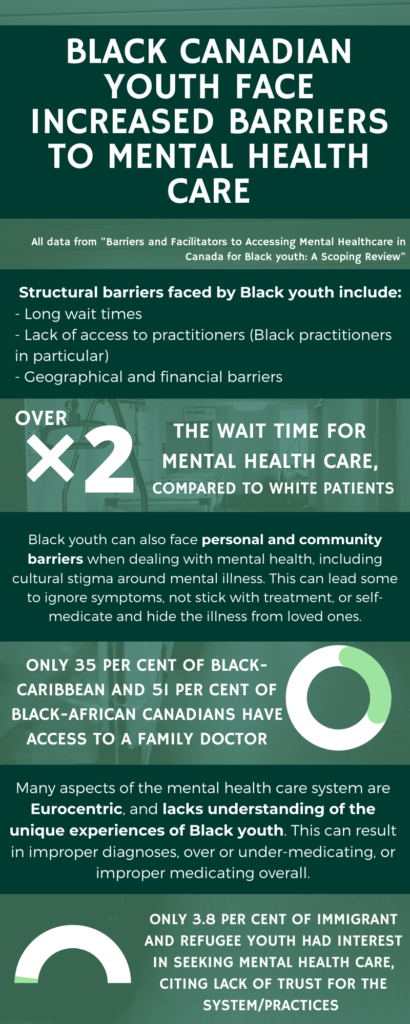

Research has shown that systemic barriers Black people face when it comes to getting help for mental health issues include longer wait times, geographical challenges, financial barriers, and a lack of access to practitioners. Organizational barriers include discrimination during care, a lack of cultural understanding and inadequate support for Black patients. Personal and community-related barriers refer to stigma.

“You have to think about broader issues such as microaggressions, racism and employment,” said Durel Allen, a social worker and therapist who owns her own practice in Toronto, Heartspring Therapy.

In many cases, Allen said, people who have access to public and mental health care receive it through employer benefits. “But if you don’t have secure employment, how’s that going to go? How are you going to pay for it?”

Federal minister of families, children and social development Ahmed Hussen told me mental health advocacy is turning the government’s attention to populations needing funding for mental health support.

“We did provide $11.5 million in mental health funding for organizations across the country supporting vulnerable populations, including Black Canadians,” he said.

All Canadians deserve equal opportunities, said Hussen. “But we also recognize that some Canadians face (systemic) challenges and barriers, especially Black Canadians, and we’re taking real steps to support their mental health and well-being through culturally appropriate programs.”

Even when access to care is addressed, the issue of culturally appropriate care persists.

“Some health-care workers do not take our pain seriously,” said Remy. “They often assume that we’re either exaggerating or we can handle it because, apparently, the Black body can take pain more than anybody else — which is false.”

She remembers once trying to convince her sister to go to the hospital.

“I thought, ‘let’s just walk into the emergency room and try to explain what’s going on with you and perhaps they can help us,’” Remy recounted.

She said her sister agreed at first, before changing her mind and requesting to be dropped off downtown instead. It wasn’t until after her sister’s death that Remy realized why her sister refused to get help that day.

“In her autopsy report, we saw that she tried to go to the hospital for anxiety and depression on multiple occasions,” Remy said. But she didn’t get any help.

“Because my sister was also dealing with addiction, they probably made some assumption that she was just looking for drugs instead of trying to provide her with help,” said Remy.

To try to prevent similar cases, Richards and Allen emphasized the importance of tailoring therapeutic approaches to meet the needs of Black clients.

“I have to use what’s called a trauma racialized informed therapy,” said Toronto-based therapist and researcher, Donna Richards. “I borrow a bit from (an) emotions focus, I borrow a bit from cognitive behavioural therapy, narrative therapy, and I put it together.”*

Culture is not the sole contributor to mental health crises in marginalized populations, wrote researchers Dalon Taylor and Donna Richards in 2019.

“Focusing on culture as the root cause of issues that racialized and marginalized populations face heightens the risk of deflecting attention from other more insidious systemic and intersectional injustices such as race and racism,” they wrote.

Nibokun agreed, noting, “If you only talk about stigma and what these Black people are doing wrong, then you don’t have to help Black people.”

Systemic racism in health care is what inspired Asante Haughton’s mental health advocacy. He said he’s taken family members to the hospital and laid out their symptoms for doctors only for them to not take him seriously, to be dismissed or told to come back a week later.

“And they came back with the same thing I’m trying to tell them the week before or the month before,” said Haughton. “It’s frustrating.”

Those experiences breed skepticism, as does the fear of aversive pathways to care. An aversive pathway to care usually means the involvement of hospital or police in a mental health intervention.

“We already have a healthy suspicion of systems and health-care systems are not exempt from that,” said Tiyondah Fante-Coleman, a researcher at Black Health Alliance.

Nibokun knows all too well what that experience is like, having been a victim of involuntary hospitalization herself.

At an extremely low point of her life in 2015, Nibokun attempted suicide. The traumatic experience caused her to seek counselling at the University of Southern California (USC) but that only made things worse.

“Two counsellors basically told me that I need(ed) to drop out of school and get a police escort to the hospital,” she said.“I did not feel safe at all.”

Nibokun said that at that time she was able to negotiate with USC counsellors to avoid hospitalization. However, she went on her own in 2015, saying she felt so vulnerable, she just wanted to get help.

The experience, she said, was far from pleasant. She described how her feelings were often invalidated by nurses.

“When I realized how awful it was, I tried to leave,” said Nibokun. “But I couldn’t.”

She fought to be out of the hospital. But eventually, she ended up in a situation where she was on the verge of hospitalization for several years. In 2018, following another suicide attempt, she was hospitalized involuntarily for the first time.

“I was threatened that if I don’t enter a psychiatric hospital voluntarily, I would be admitted against my will with less privileges,” said Nibokun.

Taylor and Richards wrote about how, “Forcible pathways to treatment are believed to be a major contributing factor to Black people’s suspicion of the medical and psychiatric systems.”

Unlike voluntary pathways, Fante-Coleman said involuntary pathways to care take away the choice an individual makes to receive mental health care. They are also problematic as the individual no longer deals just with the mental health-care system, but the judicial one.

The Community of Interest (COI) for Racialized Populations and Mental Health and Addictions released a report in May 2019 after looking at how racialized Canadians are treated in the criminal justice system.

According to the COI report, police and the criminal justice system cannot adequately meet the unique challenges necessary in assisting those with mental health issues.

“Community advocates in the space have asked for the government to work with law enforcement to make sure that when law enforcement engages Black, Indigenous, people of colour who are facing mental health challenges, they do so in a way that improves on the current record,” Hussen said.

The current record is concerning. In Canada, police wellness checks over the course of three months in 2020 resulted in four, tragic deaths. Two of them, including Regis Korchinski-Paquet in Toronto, were Black.

Currently, Haughton is working on the Reach Out response network, which aims to improve mental health crisis responses. He said the hope is to avoid “having police show up at your door or on the street where someone is in distress, in crisis.”

This could prevent the first responder from hurting or killing the person in distress, Haughton said, meaning, “You are far more likely to get an outcome that is helpful and supportive, which I think can help everybody.”

On March 2, 2020, Ontario passed Bill 178, leading to the creation of an annual Black Mental Health Day. According to the Legislative Assembly of Ontario, the day is meant to acknowledge Black Canadians with mental health problems. A year after its creation, I spent Black Mental Health day tending to my own mental health needs. As the academic year was coming to an end and graduation approached, I knew I would have to increase my efforts in finding someone new to talk to since I would no longer be able to see my university counsellor.

One of my first steps was to better understand how I process things, which prompted me to book an appointment with a psychiatrist at the Centre for Addiction and Mental Health. From them, I learned that the source of my struggles with perfectionism are the result of Obsessive-Compulsive Personality Disorder (OCPD).

The more my condition was explained to me, the more sense it made in relation to the deep-rooted issues I had been working to uncover in counselling sessions. The disorder is tied hand-to-hand with an unrealistic desire for perfectionism that cannot be met. Failure to attain perfection is what often leads to depression in people with OCPD.

Perfectionism has always been a struggle for me as a person who constantly questioned my self-worth. This is something I was able to explore at length through sessions with my counsellor. What I learned was that I had an inner, self-critic that demanded too much of me. The critic appeared in every aspect of my life, constantly pointing the finger at me whenever I failed to meet its exacting standards.

After learning about OCPD, I was convinced that the critic was tied to my personality disorder. I believed I had a huge character flaw that I couldn’t change. However, I started to change my mind after discussing the diagnosis in my counselling sessions. Like mental illness, I can’t treat my condition like an overworked battery causing a device to malfunction. I needed to accept it for what it is, something that will always be a part of me.

My counsellor encouraged me to look at the positive things about my diagnosis, like the way I can use my obsession with organization to my advantage. And while I still struggle to see past the negative, I know I will get to a point of acceptance.

In time, I will learn to accept all of me. My scars, my darkest moments, my bright “aha” moments — all of it. Because living with all these complexities is as human as we can get. We were never meant to be perfect, without flaws or cuts and bruises.

With the encouragement and help of much needed counselling, I am able to see things in a grey that is so much clearer than black and white. And what I have come to recognize is that it took immense strength for me to make the decision to seek help.

Not all people who look like me are fortunate enough to receive support, let alone quality support that can meet their needs. It’s why it’s critical we keep the fight going.