Food is one of the factors that connects us all. But what if the way we eat is actually contributing to one of the greatest environmental crises of our time?

With an appetite for change, many Torontonians are trying to address this problem, starting with what is on their plates.

The concept of “eating for the planet” has become a common sentiment amongst younger generations and is one of the most popular reasons why so many have made the switch to plant-based alternatives and veganism.

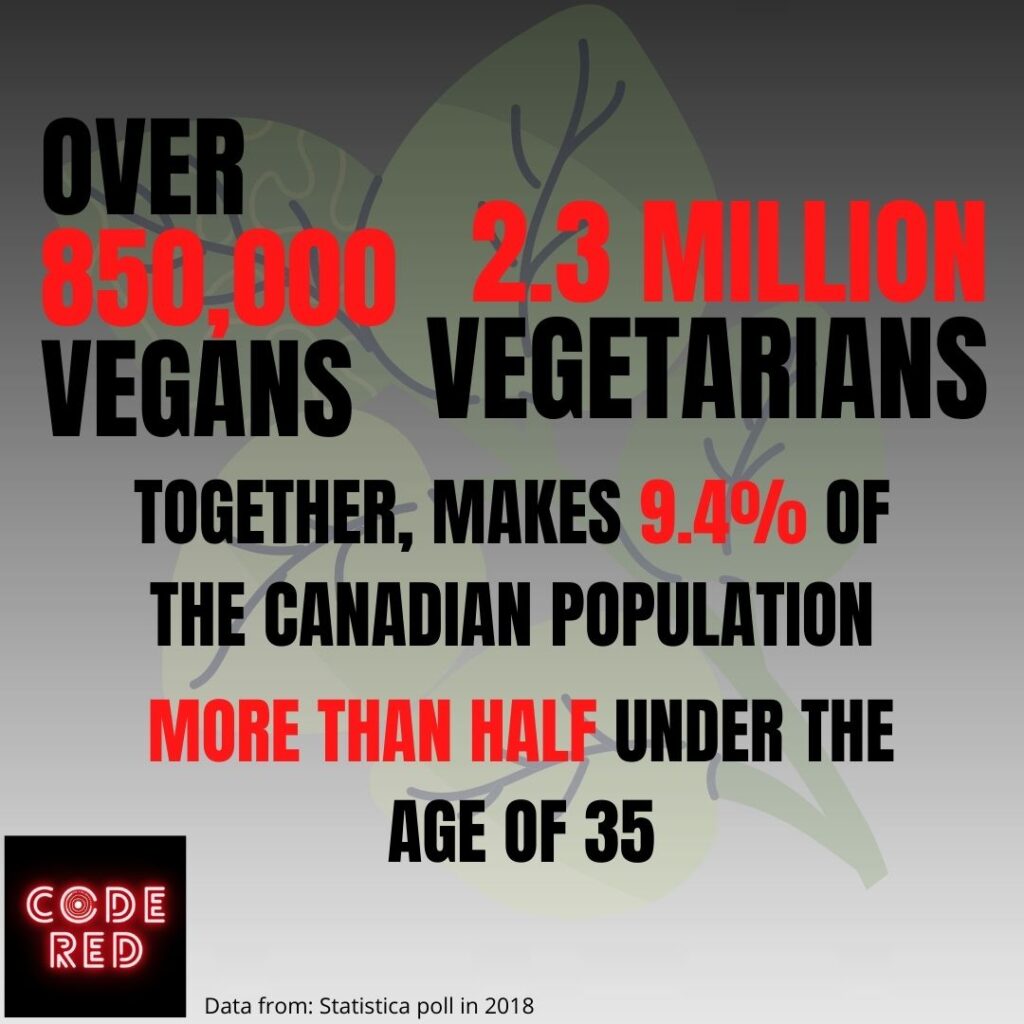

A 2018 Statista poll indicates that there are over 850,000 vegans and roughly 2.3 million vegetarians in Canada. Together, that is roughly nine per cent of the Canadian population and more than half of those are under the age of 35.

Unlike other diets, removing meat is only one part of the equation. Veganism is a complete exclusion of all animal-derived products, including dairy, eggs and even honey — staples in many households that aren’t generally given a second thought. So why go to such an extreme? And why is this movement growing so quickly amongst young people in Toronto?

The food footprint

With climate change becoming more concerning around the world, the carbon and other environmental impacts of meat consumption have become too great for some to ignore.

These concerns are not without reason. According to a study by the University of Manitoba, it takes approximately 1,590 gallons of water to produce one pound of beef (or about 7,228 litres of water to produce .454 kilos of beef). And it doesn’t end there. Pollution, antibiotic runoff, water use and contamination — and notably, carbon emissions — are all side effects of the current industrial factory farming complex.

A report from the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations says, “The livestock sector is a major player, responsible for 18 per cent of greenhouse gas emissions measured in CO2 [carbon dioxide] equivalent. This is a higher share than transport.”

The livestock sector has greater greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions than all planes, trains, cars and ships combined.

So how much does farming contribute to Canada’s net carbon emissions? The Government of Canada says that farming livestock and crops contributes to at least 10 per cent of Canada’s GHG emissions and this figure doesn’t include emissions from fossil fuels or fertilizer used in production. This could put the carbon number significantly higher.

A study by New York University and Johns Hopkins University points to the inefficiency of modelling used by the Canadian government to predict carbon outputs from farming. The report showed that the actual carbon output of farming could be anywhere from 30 per cent to 90 per cent higher than what is reported.

Aliénor Rougeot, the lead organizer of the youth climate group, Fridays for Future Toronto, and a vegan herself, says young people are taking up veganism because they worry that their futures are at risk if carbon emissions aren’t drastically cut down.

“It’s not an interest — it’s a growing fear of devastation of the environment,” said Rougeot. “There is a growing understanding that we can’t live the life that we live right now and do well and sustainably in the future.”

Environmentally, many feel they simply have no choice when it comes to going plant-based.

“I thought that it’s about me, but also about people in the Global South and people in other nations — nations that will be really facing a lot of natural disasters because of our choices here,” said David Mejia Monico, a vegan and recent Ryerson University graduate. “I thought that the fact that I knew about the choice and that it would make a difference, it was kind of like a moral imperative for me to make it.”

As some find out about the impacts of agriculture, guilt over animal rights and the climate are motivating forces to change diets and lower carbon footprints. Asha Swann, a third-year Ryerson journalism student, says it isn’t just about guilt, it’s knowing the power of consumer choices.

“I did feel guilty because I think as consumers, we have a lot of power to say, ‘I’m going to put my dollars towards this industry that can be exploitative and abusive or I can just not,’” Swann said. “So I found that for me, when I was feeling guilty about doing something like that, it’s easiest to just not make those kinds of purchases.”

Swann also elaborated on what she believes is leading the diet change in Toronto. “I think consumers are more caring. They want to know where their dollars are going. They don’t want to be blindly supporting things that don’t have the ethics to match.”

Plant-based: a solution or a false promise?

Many studies point to plant-based eating habits having positive impacts on environmental health and carbon emissions.

An analysis by the research journal Science pointed to the fact that meat and dairy only provide 18 per cent of calories and 37 per cent of protein consumed, while using 83 per cent of farmland and creating 60 per cent of agricultural GHG emissions. The report also says that a switch from the typical Americanized diet to a vegan diet could help the average person reduce their food carbon footprint by up to 73 per cent. Global farmland use could also be significantly reduced with the potential to feed more people. Even a small reduction in meat consumption could reduce overall GHG and methane release.

But is this the solution to solve the climate crisis?

Rougeot says veganism on its own ultimately will not fix climate change, but it does help reduce carbon emissions overall. She’s excited that it’s becoming more mainstream and available to more people, but also warns that not all food in a vegan diet is necessarily environmentally friendly.

“I think the choices are becoming more mainstream,” Rougeot said. “Although with that, sometimes it’s taking away from some of the benefits that I see in a vegan diet. So sometimes it’s mainstream, but it’s so processed and full of GMOs [genetically modified organisms], pesticides and things like that, that it’s not much better.”

Rougeot says that while a vegan diet may not solve climate change on its own, it is a feasible option to reduce our carbon footprints, something we should all be trying to do.

“I couldn’t ever say veganism will solve climate change, but I can say a change in diet and a change in our agriculture industry can definitely be a part of the solution.”

Rachel Parent

This article may have been created with the use of AI tools such as