Anybody can access Civic Tech Toronto’s weekly Hacknight through the organization’s Facebook.

Every Tuesday the diverse community of Torontonians meets virtually to share stories and find solutions to civic challenges through technology and design.

One particular Tuesday, a guest lecturer was invited to discuss universal basic income. At the meeting start time, community members rolled in and joined a sea of dark screens waiting for the presentation to commence.

A voice unmutes and the guest speaker is introduced.

Before the presentation could get underway, an unknown, unwanted guest enters the Zoom meeting. No one anticipated what was about to happen next.

Profanity and a combination of speech and laughter echo through headphones and across computer screens. The mystery person gained full control of the meeting.

What was supposed to be a socially impactful discussion turned into a threatening intrusion.

“That was a really pivotal moment for us… It really forced us to reexamine our code of conduct and how we invite people into our conversations,” said Skaidra Puodžiūnas, the co-organizer of Civic Tech Toronto.

Isn’t it ironic? A social media platform that is utilized to spread information, share ideas and build community is the same vehicle that invited hate, sparked fear and made people feel unsafe.

This is the contradiction that is social media.

Social media was originally created with a simple purpose: to help users connect digitally while physically apart. Somewhere along the way the purpose evolved and, instead of using social platforms as a means of gaining exposure, the virtual universe has seemingly left people feeling exposed.

In the recent instance with James Herbert Brock, social media saved the life of the 16-year-old girl he was holding captive.

After being reported missing by her parents, distress hand signals made popular by TikTok alerted another driver and aided sheriff’s deputies in Kentucky to stop the car and arrest the abductor.

But, it was also social media that resulted in her abductor obtaining photos he wasn’t meant to see.

The man who abducted her had possession of pictures that portrayed her in a sexual manner. Technology, specifically social media, has propelled the non-consensual distribution of intimate images. According to the FBI, over a quarter of all reported exploitation incidents involve an online predator asking a child for sexually explicit photos. This reality, coupled with sexual predators’ ability to find and locate targets via social platforms with ease, has driven a frightening increase in the sheer number of these types of incidents.

Once again, the social media platforms that seem to be “saving us” – in this case, TikTok – are the same channels putting us in harm’s way. “While [social media] is an incredible place to build community, you just don’t really know who you are engaging with,” says Puodžiūnas.

She explains the reality of digital identities: “The platforms just accept anyone and everyone. It takes you five seconds to create a Reddit profile, or an online dating profile, or a Facebook profile. There’s no accountability,” says the senior digital advisor with Ontario Digital Service.

With the expansion of the internet and social networking sites, there are an estimated 3.8 billion social media users worldwide, and roughly half of the 3.7 hours spent on our mobile devices each day is consumed by social and communications apps.

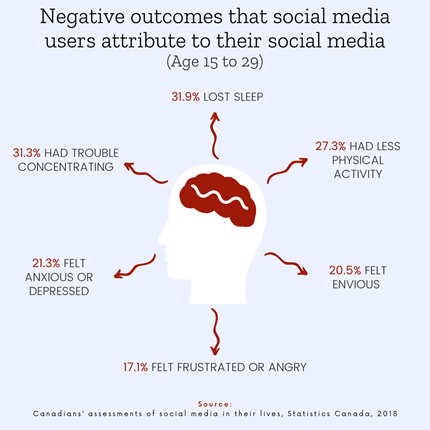

According to Statistics Canada, social media is regularly used by approximately 90 per cent of Canadians aged 15 to 34. In 2018, the Canadian Internet Use Survey examined the reports of negative effects individuals aged 15 to 64 experience as a result of social networking; some of the most concerning outcomes existed among those in their teens and twenties.

But the negative effects go beyond the increased number of sexual predators or the effects these platforms have on the mental health of users. Social media has created “an echo chamber effect,” says Robert Clapperton, Ryerson’s digital enterprise and communication research method professor.

“The worst parts of social media are what actually make it work,” he says. He explains how the algorithmic basis of how things are accomplished over social media continue to silo people into their own bubbles: “It doesn’t allow for a diversity in opinions.”

While social media platforms have been praised for providing direct access to an unprecedented amount of content, the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS) conducted research on how these platforms influence information spreading and the echo chamber effect on social media.

According to PNAS, an echo chamber is an online environment in which users’ opinions get reinforced by interacting with like-minded sources. The environment tends to widen ideological divisions and limit exposure to diverse perspectives.

The academy’s research found that different platforms foster different levels of segregation in online communities depending on the platform’s feed algorithms and their social networking features.

“Technology is supposed to give us immediate access to whatever we want to know, but that has now made us more blind to what is actually going on,” says e-commerce business owner, Genevieve Vendittelli. She explains how we simply will not hear about it “if it doesn’t fit in our ‘belief system algorithm’ encoded onto our phones.”

While these sorts of algorithms increase polarization, the research concluded that when polarization is high, misinformation quickly proliferates.

Yet again, one of social media’s greatest assets — the power of spreading information — is also its greatest weakness.

So, the question becomes: with all these contradictions, do the benefits of social media outweigh the drawbacks?

For Vendittelli, the answer is simple: “While it varies from user to user, the benefits I get out of social media outweigh the drawbacks because of my awareness. Social media, for me, is whatever you make it to be.”

Vendittelli explains how she uses social media to get inspired, reach new audiences and create relationships with other brands. “On a business level, it provides great metrics about our target market, what content they want to see, and when they want to see it.”

While she has fallen victim to triggering posts before, she says the key to breaking free was to “have enough self-awareness to not be so consumed by what you’re consuming. You have the power to mute content on your feed, unfollow people you don’t gain value from [and] set limits to reduce your daily usage.”

She emphasizes that “it’s the end-receiver of the content’s responsibility to choose what they consume… If you’re going to let those triggering posts get the best of you, then yes, the drawbacks definitely outweigh the positives.”

Although the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders has not officially identified social media addiction as diagnosable, it does not change the reality that unhealthy usage can cause distress and negatively affect people’s lives.

Ryerson biomedical science student, Marisa Chiaravalloti, used the example of Snapchat streaks – the number of consecutive days two people have been sending Snapchats to each other – to highlight how social media can become unhealthy.

She explained how, in high school, she would keep ‘streaks’ with people but eventually realized that she was sending snaps to people she hardly spoke with anymore. “I was just doing it for the sake of having a number on my phone,” said Chiaravalloti. “It gives everyone this false narrative of being connected.”

Though Chiaravalloti sees the benefits that exist on social media for businesses, she ultimately says the negative emotional effects these platforms have on people are not offset by the rewards: “It’s close, but I think it does more bad than good.”

For Ryerson alumna and registered dietitian, Cristina Cappucci, the answer isn’t as clear-cut. “Perhaps it’s quite equal – the drawbacks of social media could be very, very severe, but the benefits could be very, very amazing and life changing.”

As an anti-diet dietitian that started her business amidst a pandemic, Cappucci says social media has allowed her to achieve “reach” without boundaries.

“It’s amazing to be able to change so many people’s lives without meeting them,” she said. “I have had people who are clients and people who aren’t clients message me and tell me how my social media presence has helped them feel better about food and their body image.”

But she points out that when somebody is new to social media, the experience can “start off negative if the algorithm starts putting [people] down that rabbit hole.”

In the health and nutrition industry in particular, social media can be very contradictory: “I have clients who are following me and my account where I talk about making peace with food, but [at the same time] are also following influencers who are body-shaming.”

While the answer is clearly subjective as to whether the benefits outweigh the drawbacks, Puodžiūnas believes that we have an opportunity to rethink the role social media plays in our day-to-day lives. “It’s hard to imagine a life without social media. I don’t even know if we are at a point where we could not have [it] part of our lives.”

Correction: This article has been updated to remove the phrase “Nazi symbols.” The source said she used it in error when intending to refer to something else.