Even though Tara Mulcahy Konop considers herself one of the lucky ones, the pandemic still upended her life.

The 21-year-old Ryerson student started the pandemic at Concordia University in Montreal, paying their bills through a part-time job with Starbucks. When her location closed for two weeks, she lost thousands of dollars worth of work shifts. When the store reopened with limited hours, they couldn’t get enough work to pay her bills.

Konop was forced to leave Montreal, transfer universities and move back to her family. It all happened so fast.

“It got to a point where I could barely afford food and rent, let alone tuition,” they said, “I didn’t have a choice.”

RELATED: The great campus return?

Since moving back to Toronto and enrolling in Ryerson’s English honours program, some of Konop’s financial struggles have stabilized, but Zoom classes have taken a toll on their mental health.

“They didn’t even take a week-long break to teach professors how to use Zoom,” she said, which meant teachers, “just didn’t know how to help students.”

Konop’s experience is indicative of the broader student experience. The pandemic has exposed overlapping mental health and financial crises that have been bubbling under the surface for a while now. Students are becoming more vocal with their concerns, even going so far as to reconsider the value of their education as the high price of tuition forces some to delay their degrees or drop out altogether.

“My only wish is that when we consider student wellness, we don’t just consider their social and emotional wellness.”

Zamir Fakirani, president of the University Students’ Council at Western University

“Responsibility shouldn’t be on the students struggling in isolation,” said Niki Michas, an organizer with Socialist Fightback at Ryerson University.

Remote learning might have made organizing strikes trickier, but Michas said that shouldn’t be taken as a sign students are OK with the status quo.

“There were tons of students who were frustrated paying full tuition for online school,” Michas said.

Konop, who worked more than 25 hours a week pre-pandemic to afford tuition, rent and food, said she would have joined in a strike during the pandemic—and she’d still join in a strike today.

“I definitely would have,” she said.

Students today have to work more hours to pay for post-secondary tuition than previous generations, according to a 2018 RBC report. In 1990, it took an average of 293 hours of minimum-wage work to pay for one year of university for a domestic student. In 2018, it took an average of 505 hours.

While the University of Toronto and George Brown College lowered tuition for students during the pandemic, Ryerson opted not to, saying that virtual learning does not cost the university any less than in-person. It does, however, impact quality: a report compiled by the Canadian Alliance of Student Associations (CASA) found that 56 per cent of students surveyed say the lack of academic support has been worse online.

Even promised support from the Ryerson Students’ Union hasn’t materialized. The union cut funding to student grants and delayed the launch of important initiatives, including one that would have seen 100 new jobs created on campus.

READ MORE:

- Amid worsening mental health, students are anxious to return to in-person classes

- Pandemic learning left students with ADHD behind. Here’s how a campus return could fix that

- Ryerson’s student groups prioritize making religion more relatable on campus

- More online therapy key to dealing with growing demands for mental health counselling

One-quarter of Canadian university and college students aged 18 to 20 either dropped out or postponed their studies during the pandemic, according to a new research report soon-to-be released from the Future Skills Centre.

Fiona Deller, the centre’s chief operating officer, says Black, Indigenous and disabled students left university at a much higher rate than their peers, and that workers under the age of 25 were the most likely to lose their jobs during the pandemic.

The number of students reporting feeling stressed has remained high, at 77 per cent in 2020 and 2021, according to a survey conducted by the Canadian Association of College and University Student Services.

Overall, CASA found those who said the pandemic has made them feel most worried are the same folks who have been hit the hardest financially.

The high stress levels come in the midst of major changes to how mental health services are offered to students. The shift to online services was rapid — within three weeks, 90 per cent of post-secondary institutions made the switch from in-person counselling to online sessions, CASA found.

Zamir Fakirani, president of the University Students’ Council at Western University, is appreciative of the quick switch that universities made, but believes that post-secondary institutions may have forgotten to consider other challenges students have been facing.

“My only wish is that when we consider student wellness, we don’t just consider their social and emotional wellness,” he said.

“I have to work eight-hour shifts three times a week, and there’s almost no financial support coming from anywhere.”

Tara Mulcahy Konop, Ryerson student

David Robinson, executive director of the Canadian Association of University Teachers, says that many of these experiences are shared by faculty as well.

“It’s not just enough to say, ‘here’s the wellness centre of the university, if you’re feeling stressed, call this number and talk to someone,’” he said. “It’s also looking at the material conditions that are causing the stress, which was [often] overwork.”

For some, working and studying from home led to a greater inability to disconnect from work, subsequently increasing the amount of time spent on school and work-related tasks. Students have coped with unique stressors, including grades and post-graduate employment, according to CASA. Despite these increased challenges, 53 per cent of students surveyed by CASA said that they had difficulty accessing campus-provided mental health services.

The report noted that international students, in particular, were more likely to report challenges accessing mental health services than domestic students.

“Changes which under normal circumstances take years or decades took place in a few weeks,” the report noted, causing an “enormous amount of distress.” International students had to contend with the pandemic, fears for family far away, as well as time-zone changes that impacted their learning and career opportunities.

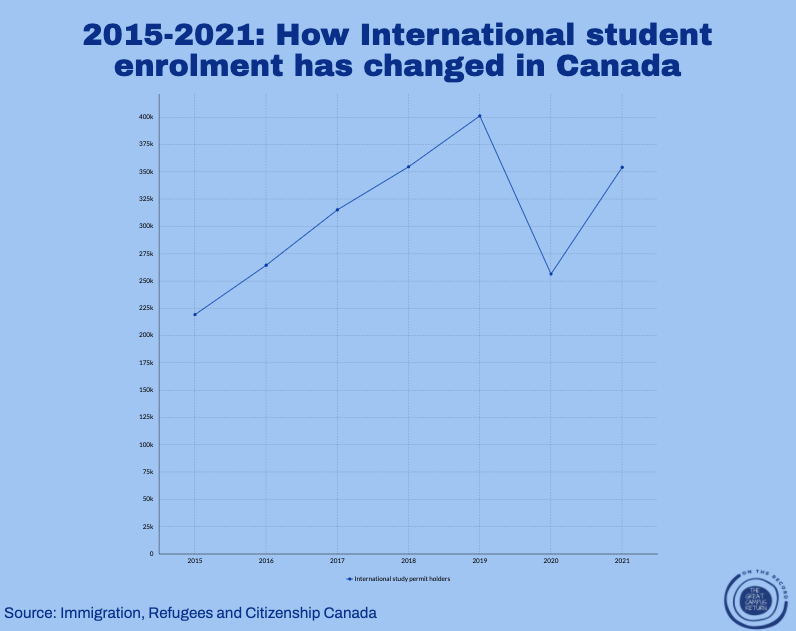

International student enrolment in Canada dropped in 2020 for the first time in years because of COVID-19 related travel restrictions.

Tuition fees from international students contribute over half of Ryerson’s total revenue. During the pandemic, the international student population shrunk by 65 per cent, costing the university at least $49 million in expected tuition funds.

“There’s no question [international students] are a really valuable asset for the universities in terms of their revenue stream, as universities have become strained and stressed by provincial governments,” said John Shields, a politics and public administration professor at Ryerson.

READ MORE:

- Ryerson’s proof of vaccine system leaves room for errors, experts say

- Ryerson 1 of only 7 Ontario universities choosing not to publicly report COVID-19 cases — even as a new variant sweeps the globe

- What Ryerson isn’t telling us about the return to campus

Shields says international education is necessary in a globalized world. He says sending Canadian students abroad and hosting international students here also makes Ryerson’s campus and society more “cosmopolitan.”

“We live in a global world where we are involved in a lot of trade with many different places, and that’s the future of the economy,” he said. “The more we are cosmopolitan and attuned to that, the better off we are, economically, but also socially and culturally.”

International students returning to campus directly impacts Canadian students, says Usha George, director of Ryerson’s Centre for Immigration and Settlement. She says students become more culturally sensitive and aware when they are interacting with students from other parts of the world, rather than reading what may be outdated information in a textbook.

“Not only do they enrich our understanding of ourselves but the students get to understand each other better, the stereotypes can be broken down,” said George.

But the path back for international students is paved with obstacles, as journalist Monique Vigneault explains. With the university’s plans to limit remote learning options, those students must now repeat — in reverse — the major educational changes CASA found caused extreme distress.

Not having to make such a transition is part of why Konop still counts themselves among the more fortunate. “Luckily, I was still in Canada. [Other] people were being sent all the way home to different countries,” they said.

RELATED: Why compassion is key to making January’s return to in-person learning smooth

Still, Konop’s first year of university, and first year away from home was anything but easy. She says that she often dreams of what life would be like if tuition was less of a financial burden.

CASA’s report emphasized that students are still facing challenges relating to the pandemic, noting that despite an end seemingly in sight, “these struggles should not be minimized or downplayed.”

Although Konop looks forward to the end of the pandemic and the return to in-person classes, the reality of her financial position still persists.

“I wish I would be able to focus fully on my studies,” they said. “I have to work eight-hour shifts three times a week, and there’s almost no financial support coming from anywhere.”