What the conversation about renaming Ryerson University reveals about struggles of BIPOC journalists to tell their story and bias among white journalists in Canadian media

Publisher’s note:

It is crucial that readers understand the enormous value placed on editorial independence at the Ryersonian, and how that has informed the process that led to Deepak Bidwai’s opinion piece. In October, when the instructors leading the Ryersonian received a draft of this essay, they saw some of it was critical of the Ryersonian and the School of Journalism itself.

To protect editorial integrity, I hired an external handling editor and appointed a delegate publisher to be the final eyes on the piece. More details below.

It is our responsibility to you, readers, and to the public, to assure you we have gone to unusual lengths to ensure there was no actual or perceived conflicts of interest in a story that may well make us uncomfortable.

— Janice Neil, chair, School of Journalism and Publisher, The Ryersonian.ca

Article

In early October, the Ryersonian published an opinion piece titled “What’s in a name change?” by my colleague Alex Cyr, listing reasons not to change Ryerson University’s name.

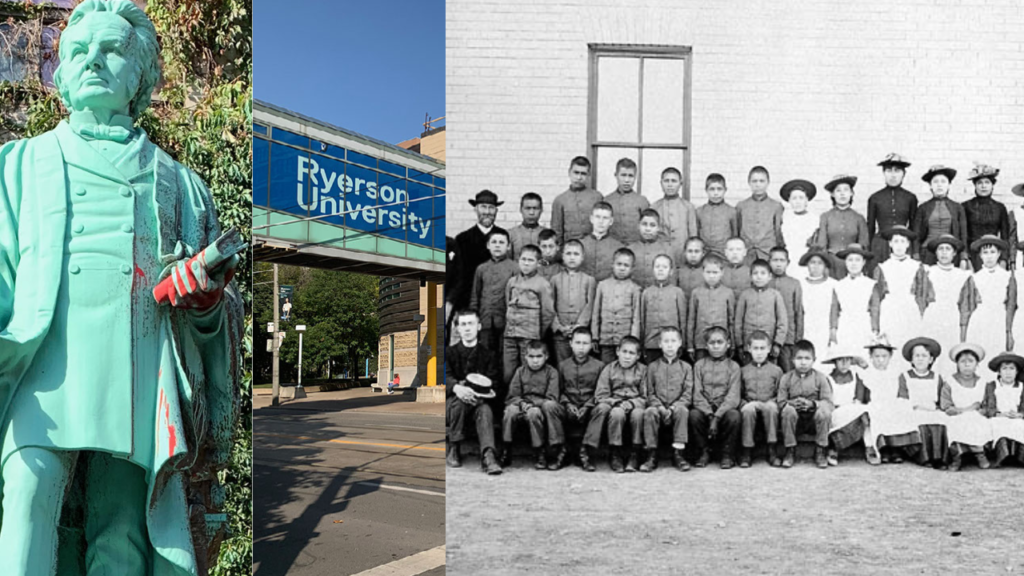

To change or not to change is not a new debate. The university faces growing calls to dissociate from its namesake Egerton Ryerson, a controversial 19th-century colonial educator whose statue stands on campus grounds.

I was furious and disappointed with Cyr’s article, which was published as a part of Monumental Challenges, a series examining Ryerson’s legacy, reconciliation and what to do with monuments and institutions that memorialize problematic historical figures.

In his piece, Cyr introduces Egerton Ryerson as a missionary, preacher, teacher and advocate for free education. That Ryerson played a role in developing residential schools and the resultant violence inflicted on Indigenous children is not addressed.

The fact that decades before the Canadian government began to use residential schools to systematically and inhumanely separate Indigenous children from their families, Ryerson wrote a report explicitly proposing such racist measures is not even mentioned in Cyr’s article.

I reached out to Cyr in late November to understand the thinking behind his approach. He told me that his focus was not Egerton Ryerson’s story, but the financial costs associated with changing the name of the university.

Peter Bakogeorge, one of my instructors and editor of Cyr’s article, did not dispute Ryerson’s controversial past but, in meetings, an interview and via email, justified the exclusion of Ryerson’s problematic past from Cyr’s article.

“I don’t think that has to be hammered home in every story of the package, because it’s the reason that the package exists,” Bakogeorge said.

Cyr’s and Bakogeorge’s arguments that Ryerson’s racist ideology and policies can be excluded demonstrates the fundamental and alarming problem with Canadian media, which has been firmly in the grasp of white people.

The troubling worldview perpetuated in Cyr’s piece dominates Canadian journalism. This white version of history ignores centuries of Indigenous bloodshed.

As my Métis colleague Emily Peotto wrote in her own contribution to Monumental Challenges, Cyr’s article “reflects another, more sinister sentiment that has been building on campus for years. One of anti-Black and anti-Indigenous racism, failed reconciliation and years of stagnancy.”

***

Before proceeding further let me explain what my article is not about. It is not a commentary on the character of Cyr, Bakogeorge or anybody else featured in this piece. Personally, I have a great respect for Bakogeorge. I was educated in India and the U.S. and have met very few instructors who have such dedication and passion for their work. I have known Cyr for more than a year and we have become good friends. He is someone you can talk openly with and count on to have respectful conversations.

My article is about what I find troubling in the whitewashing of colonial atrocities and their consequences. Cyr told me that his argument was not that the university’s name should stay, and that he did not have a good opinion about Ryerson. To reflect his view, the subheadline was changed from recommending that the name should stay to listing the costs of the name change. Unfortunately, the article does not do enough to address the problematic past of Ryerson.

In in his article, Cyr calls the impact of the residential schools intergenerational trauma for Indigenous people, and not cultural genocide. When I asked why, Cyr told me he felt Ryerson’s role in the creation of residential schools was “ambiguous.” But when I asked how he came to this conclusion, Cyr told me he relied on an article in the Globe and Mail by Marcus Gee that failed to interview even one Indigenous person, downplayed Ryerson’s official report advocating residential schools, praised him for educational achievements that helped white people, justified his views by saying that he was a product of colonial era and concluded that “blotting out the past is a mistake. Old Ryerson should be allowed to stay.”

But Karly Cywink, an Ojibwe woman from Whitefish River First Nation and a media production student at Ryerson, disagrees.

“We need to take the statue down… It’s doing more harm than is helping anybody,” Cywink said. “For me, a statue is a physical representation glorifying a person. And so we are actively glorifying Egerton Ryerson in the heart of our campus.”

Ryerson, a militant Methodist, held Christian supremacist beliefs. He wrote in his formal report on residential schools to the Assistant Superintendent General of Indian Affairs that the “North American Indian can not be civilized” without Christian religious teaching. He said it was necessary that Indigenous children stay together and be taught to become agricultural labourers. He warned against large expenditures on these schools.

Ryerson’s beliefs were not innocuous, but have been at the core of white settler actions against Indigenous people colonized in Australia, Asia, Africa and the Americas. The intended purpose of the Canadian residential school system was the eradication of Indigenous cultures by spreading Christianity and western philosophies. The result was cultural genocide, as clearly demonstrated in the Truth and Reconciliation Report. Yet in his piece, Cyr sets that history aside.

White people honour Ryerson for the good he’s done but whitewash the negative consequences of his actions, said Karyn Pugliese, an assistant professor in the journalism school and a member of the Pikwàkanagàn First Nation in Ontario.

“If (residential schools) had happened to non-Indigenous families, white Canadians, then they would not be honouring (Ryerson) right now,” she said.

***

The reason the article glided through white editors so smoothly is, to me, because of a lack of empathy towards the pain and suffering of Indigenous people — a lack of empathy I see reflected throughout the journalism school.

The people who should be listening aren’t. Instead, they’re acting as gatekeepers in the name of publishing so-called balanced reporting. Having mostly white professors and students make editorial decisions, especially on issues affecting Black, Indigenous and people of colour (BIPOC) communities —as was the case at the Ryersonian this past semester — makes the matter worse. (Bakogeorge told me the masthead is typically more reflective of a diverse student population and changes every semester.)

During the first project planning meeting for Monumental Challenges in mid-September, I brought up a book by Susan Neiman, called Learning from the Germans: Race and the Memory of Evil. It’s a thought-provoking book about the multi-decade process of Vergangenheitsaufarbeitung —“coming to terms with the past” — by which Germany has reckoned with its Nazi history and the Holocaust. I recommended that the Ryersonian approach Canada’s colonial past through this project the way Germany has its darkest period.

As I remember it, H.G. Watson, Bakogeorge’s co-instructor, dismissed the comparison as not relevant to Canada. However, when I spoke with her later, she did not recall rejecting the comparison. “I’m sorry that we didn’t talk about it (the book) more,” she told me. “I don’t feel that way now. I think that it (the book) is very much relevant.”Still, I mentioned my recollection of our initial exchange when I spoke with Neiman herself late last month.

“They should read the first chapter of my book, because I knew people were going to make that objection,” said Neiman, who is Jewish.

“I acknowledge all the ways in which those events (slavery, colonization) were not alike. Very few historical events are exactly alike.”

In her book, Neiman, the director of the Einstein Forum in Berlin, explains why people today might be reluctant to compare their history with the horrors of the Holocaust.

“Evil is what others do. We want our ancestors to be honorable, and honored,” she wrote.

My discussion with Neiman left me with the impression that many white people can’t accept the reality that their ancestors’ actions and policies made their lives better at the expense of non-white people. Or, that as good and benevolent as these historical figures were to their own people, they were often equally brutal to non-whites.

***

As I said, I was furious and disappointed with Cyr’s article—but I was not surprised to see white journalists and instructors at the Ryersonian downplay Ryerson’s racist views. After all, the same has been done by prominent Canadian historians, including Donald Smith in a 2017 article in The Globe and Mail.

Smith, professor emeritus of history at the University of Calgary, cherry-picked convenient facts from Ryerson’s autobiography, The Story of My Life, to prove that Ryerson was not anti-Indigenous and rather fought for Indigenous rights.

By excluding Ryerson’s racist views, Smith might well have succeeded in convincing uninformed readers that Ryerson was not anti-Indigenous. But he also shows the inherent insensitivity and biases that can be found among many white historians and journalists toward colonial atrocities.

Prominent Canadian voices continue to embrace historic leaders like Ryerson by ignoring their racist policies and actions. In late August, protesters in Montreal toppled a statue of John A. Macdonald, Canada’s first prime minister, for his racist policies and views. Conservative Party Leader Erin O’Toole tweeted in response to the incident that “Canada wouldn’t exist without Sir John A. Macdonald.” Alberta Premier Jason Kenney went one step further and called Macdonald a hero. Both neglected to talk about the brutal price their “hero” made Indigenous people pay for Canada’s very existence.

A recent article in the Toronto Star details how the Government of Canada, through information shared on official websites, whitewashes many atrocities. In particular, it highlights how a web page about John A. Macdonald calls him a nation builder and “amplifies his dreams of building transcontinental railways but makes no mention of countless deaths of Chinese workers toiling to build that infrastructure.”

There is also no mention of Macdonald’s anti-Indigenous policies, including promoting residential schools. Such writing deprives readers of a comprehensive view of their own history. That doesn’t surprise Pugliese, who said mainstream Canadian history often ignores Indigenous perspectives.

“We are left out,” she said. “Indigenous people… we’re often not even included in Canadian history courses.”

This ignorance percolates the education system and the media. Even the Ryersonian’s current editor-in-chief Patrick Swadden said he was shocked to learn in our September newsroom meeting that Egerton Ryerson wrote a report promoting a system similar to residential schools.

“I didn’t know a whole awful lot about the situation,” Swadden told me later, adding that he was disappointed not to have learned more about Indigenous history in Canadian schools.

I am confident that if Canadian school curriculums taught Indigenous history in the way German schools address their Nazi past, the idea of changing Ryerson University’s name would not be considered a cost to bear, but a value-add.

During an editorial meeting on Oct. 8, immediately after Monumental Challenges was published, I expressed my displeasure about Cyr’s piece and indicated I wanted to write a rebuttal to its flawed arguments and omission of the pain and suffering that Indigenous people experienced because of Ryerson’s policies.

But that meeting felt like a conversation I have been forced to have over and over since arriving at Ryerson a year ago. In it, I had to explain to four white people — two instructors and two students in senior newsroom roles — what was wrong with Cyr’s article.

I was frustrated that my points about what was inherently wrong with a piece that ignores Ryerson’s racist views did not seem to penetrate the hearts and minds of my white colleagues and instructors.

When I realized that my history, experience and worldview were so different from theirs that we were living different realities, I decided to drop my idea — a decision made under the weight of far too many similar experiences.

***

Living in a white person’s world where their distorted version of history prevails, I have learned to manage my expectations, disappointment and anger. Not only because any criticism almost always gets dismissed, but because there is a high price to pay for speaking out.

I grew up in India, in a society that favours lighter-skinned people. I had an inferiority complex for many years as a result. It wasn’t until I moved to Boston in 2012, where many of my friends were Black, that I started to overcome that feeling. The way they accepted me and the way they spoke openly about racism in the U.S. encouraged me to speak out, too. I brought that attitude with me when I moved to Canada in 2018.

But even here, I paid a price for speaking up.

In 2019, I heard work colleagues at an Ontario pension fund call rape India’s favourite sport, refer to outsourced IT centres in India as an “empire,” demean employees for speaking out against problematic policies, make fun of transgender people and harass me based on my caste.

I did not receive support when I brought these complaints to the manager and when I finally took many complaints to HR and the managing director, I was told not to speak to anyone while my complaints were looked into. The next day, I was humiliated and ejected from the office in the middle of the day. I have since filed a complaint with the Human Rights Tribunal of Ontario (HRTO) and the company has refused to comment while my case is active. The company’s lawyer has asked the HRTO to dismiss my complaint.

I had a choice, then. I could ignore the terrible treatment to keep my six figure salary or stand against it so that my son might have a better world to live in. I chose to switch careers, in part because I strongly felt that journalism was the last hope in society’s fight against discrimination, racism and bigotry.

But I was naive to expect that all people at a school named for Egerton Ryerson, of all people, would be more open and tolerant than the workplace I filed a human rights complaint against. My attempts to start a new chapter fell flat within the first few months in this journalism program because I forgot — for a moment — that you cannot outrun racism.

There is a price to pay not just for speaking out but also for simply being who I am. There is a price for being born into a certain caste from a formerly colonized country and with immutable attributes like dark skin and non-European facial features.

For me, and many people like me, the effects of colonialism — even in a place like Canada where white media bombard us with the narcissistic narrative of how nice Canadians are — do not exist only in the past.

One day in January 2020, I was told to leave a Ryerson research facility because it was supposedly closed. Yet, I went there after it was opened and I saw some of my white classmates sitting inside. Only after I pointed that out did the campus official ask the other students to leave, rather than let me in.

A few weeks later, when I was inside that facility, the same campus official reminded all the students present about safety protocols, such as making sure not to let in anyone who wasn’t authorized to enter. Then, the official came up to me and asked if I understood. Being singled out was humiliating. I stopped using the facility after that.

I filed a complaint with the University’s Human Rights Office in March, but after months of delay and dealing with multiple people, the final fact-finding report in late August did not have all the details I provided. The University hired an external investigator in October to look into my complaint and the investigator contacted me to ask for details again. To me, telling others about these experiences over and over is equivalent to reliving them. These repeated humiliations make me wonder if it was worth reporting the incidents in the first place.

In the end, my concerns appear to have gotten lost in the university’s unsympathetic bureaucracy. The way the university handled my concerns diminished my confidence and robbed me of any hope for justice. (A Ryerson Public Affairs spokesperson told me by email that the university cannot publicly comment on specific investigations or complaints and that it takes matters like this seriously.)

In class, too, I have faced micro-aggressions from my white professors and peers simply for trying to express my views. In fall 2019, during a group meeting about a class project, a white student undermined my research findings about inherent bias in 19th-century Canadian media by dismissively suggesting “the world was a shit-show back then.” The student then took over my part of the research and the final presentation lacked the information I thought was relevant. The student, who has since become a good friend, has apologized.

In another class, a professor repeatedly told me to “stick to the reading” whenever my written response was critical of white-centred perspectives. Later, he told me that he has become more open to hearing such critiques from students.

Once, in conversation with a professor I admire, I expressed my desire to write about the way the university handled my harassment complaint. The professor warned me to avoid criticising the university and the journalism industry in Canada until I make it in journalism. I recently reached out to that professor to ask about our interaction. She denied saying this to me, writing that she had been offering advice on how to avoid defamation suits.

I know her warning not to criticise the university was well-intentioned because we live in a world that tends to punish the victims by denying horrible actions happened and discrediting anyone who says otherwise — sometimes ruining their careers and livelihoods in the process. But my reality is professors who tend to dismiss my perspectives.

Until recent newsroom discussions where students at the Ryersonian spoke up collectively about the challenges BIPOC journalists face, I have often felt alone whenever I’ve objected to what we were being taught.

***

After the initial disappointment of the Oct. 8 editorial discussion about the shortcomings of Monumental Challenges, I got strength from some words of encouragement from Paula Tran, one of my colleagues at the Ryersonian.

I was further emboldened to keep speaking up after Tyler Griffin tweeted his criticism of the article. His tweet is an excellent example of how BIPOC students empower one another. I forwarded the tweet to Bakogeorge to convey the message that I was not alone. As more people started retweeting and liking Griffin’s message, I got the strength to talk more openly with my instructor and our subsequent conversation made me feel like he was listening.

During the next editorial meeting, on Oct. 9, many students — BIPOC, as well as white — spoke out to express their displeasure with the special project. Dania Ali, one of my fellow reporters, questioned the idea of objectivity in journalism. I reached out to her to better understand her arguments.

“We’re all a product of our experiences and therefore it is virtually impossible to remain objective,” she wrote. “Alex(Cyr) and other white individuals on the masthead who vetted this project could have confronted their implicit biases.”

It has been illuminating, too, to listen to my colleague Emily Peotto insist that the Ryersonian needs to make sure a piece doesn’t get past the editing stage without any BIPOC sources in it.

In a direct message underscoring her comments from our editorial meeting, Peotto told me, “a piece around Indigenous issues isn’t just missing a part of it if there’s no Indigenous voices, it’s not a piece at all. And it shouldn’t be considered one.”

Peotto made it clear during the Ryersonian meeting that the name of the publication is a major barrier to inclusivity, noting she would never tell her family or any other Indigenous person that a publication named after a colonizer will treat their story well. Nor would she advise them to speak to its reporters.

Cyr’s wasn’t the only story lacking Indigenous perspectives and voices. As Peotto told me, it is the Ryersonian’s responsibility “to understand why we’re not getting those (Indigenous) voices and that it’s our fault.”

She believes that more inclusiveness at the Ryersonian will help earn that trust. After all, she wrote, “The Eyeopener has no problem getting BIPOC voices because they’re an inclusive publication.”

My instructors seemed more receptive to criticism during the Oct. 9 meeting than before. Bakogeorge said Cyr’s opinion piece had slipped through because the editors and instructors were rushing to meet the deadline, although he later said he misspoke and the article was not rushed.

Still, it’s worth noting the discrepancy between the lack of editing on Cyr’s piece and the extensive editing of a video I co-produced, about Egerton Ryerson’s life and policies. The video was delayed in the interest of getting the facts correct.

Watson, who edited it, held my partner and me accountable to every single word we included in the video, especially those that put Ryerson in a bad light. I was grateful for that. I wanted to have the facts straight. Yet Cyr’s piece didn’t seem to receive the same level of scrutiny.

During the Oct. 9 meeting, Bakogeorge expressed regrets that students had not felt safe enough to express their displeasure earlier. He called BIPOC students’ criticism “a master class” for him. It was empowering to me that students created the opportunity to speak and be heard. I left the meeting with the hope that with strong BIPOC voices we can force our white colleagues, teaching assistants and instructors to change for the better.

Nevertheless, as Peotto made clear, the Ryersonian’s name is one of the biggest barriers to having Indigenous students trust the publication. At the Oct. 9 meeting, several students — myself included —proposed that the journalism school should lead the way for the rest of the university by changing the name of the Ryersonian.

We weren’t the first to raise the name change issue. Duncan McCue, the journalism school’s current Rogers Journalist in Residence, said students have brought up the need for a name change with him in the past. But our Ryersonian meeting prompted further conversations as Bakogeorge and Watson discussed the potential of a name change with Janice Neil, the Ryerson School of Journalism (RSJ) chair and publisher of the Ryersonian. From there, it was discussed at a faculty meeting on Dec. 7.

At that meeting, journalism faculty and instructors unanimously passed a motion to examine changing the names of Ryerson masthead publications, the Ryersonian and the Ryerson Review of Journalism. There was also a motion passed to form a committee to draft a summary of current initiatives at the journalism school to uproot anti-Indigenous and systemic racism, to identify key areas for improvement, and to recommend further action.

During that meeting, McCue, who has been working with the instructors to ensure that Indigenous issues and content are covered through the whole curriculum, acknowledged the work done by the RSJ is an “ongoing process” and said “there is more work to be done.”

“We don’t want this to be simply a knee-jerk reactive discussion about changing the name for the sake of changing a name,” said McCue, who is a member of the Chippewas of Georgina Island First Nation. “There is deeper work that needs to be done.”

The faculty will meet at a later date to decide next steps. But already, I feel both overwhelmed and assured by the commitment from the journalism school to address the systemic issues facing our newsroom, the university, and Canadian media as a whole.

***

A lot has happened in the two months since: heated discussions, training sessions and intimate conversations. In the two months since Cyr’s article was published, there have been other meetings organized to discuss the piece and, in general, how reporters can do better. But I did not attend.

I don’t want to participate in another meeting where the burden falls on BIPOC students to prove their points over and over again. I am ready to see a plan of action from RSJ that addresses systemic racism, including a commitment to a name change.

My experiences at my pension-fund job and, now, at Ryerson have taught me that the lived reality of BIPOC professionals and students stands in stark contrast to the images of inclusivity and tolerance these institutions try to project.

“We get there by listening when inequity and racism are occuring in our classrooms and in our school, and the professional journalism community. We get there by making changes when our practices and procedures fall short,” Neil wrote to me about what the school can do to bridge the gap between the image and reality.

These experiences made me reflect on my place not only in journalism but Canadian society at large.

Will I always be seen as someone who should be happy with the inequality in Canada because life back home can be worse? Am I a token representative who is welcomed so long as I don’t practise journalism that goes against dominant white narratives?

The events leading up to this semester have left me wondering what it would take to stop Canadian journalism from whitewashing history.

I still don’t have all the answers, but BIPOC students have started conversations to actively engage with the school moving forward to make sure our voices are heard. We will pass the torch of leadership and engagement, which we inherited from those who came before us, to the students who come after us.

Many white people say don’t change the name because that would erase the history. I disagree. If anything, we would be replacing an incorrect version of history that has been allowed to dominate Canadian media for too long.

I say change the name, remove the statue and acknowledge the historical lie we have been living. I agree with those who say that we can’t erase history by removing names. That’s why, in my view, the top of the publications’ websites should acknowledge the name change and include an introduction to Egerton Ryerson and his racist views and policies.

We should continue pushing to have Ryerson’s name and statue removed. The final, exclusive authority on what should replace them should lie with the university’s Indigenous community.

Pugliese said she’s heard a number of views from Indigenous professors at Ryerson on what to do with the statue, including replacing it with monuments for children affected by residential schools. While there’s no consensus yet, she said the discussions are encouraging.

Regardless, she said removing the statue or renaming institutions and publications is not the end of the conversation. “Just removing things is not always the answer,” Pugliese said. “It has to be a recognition that at one time, these things were considered acceptable.”

Clarification: This post was updated on Jan. 8th to more accurately reflect H.G. Watson’s response to Deepak Bidwai recommending the Ryersonian approach its Monumental Challenges project the same way Germany has reckoned with its Nazi history, as outlined in Susan Neiman’s book Learning from the Germans: Race and the Memory of Evil.

Publisher’s note continued

The first edition of the Ryersonian rolled off the presses 72 years ago last month. Just a year later, the beginning of what became a long-running battle over editorial independence was fought: in 1949 the newspaper staff went on strike to protest what they saw as heavy-handed control by Ryerson University administration.

It took a mass resignation a decade later to establish the freedom the Ryersonian writers, reporters, editors and producers enjoy from interference by the publisher (the school of journalism) or its owners, the university. It’s crucial that readers understand the enormous value placed on editorial independence, and how that has informed the process that led to Deepak Bidwai’s opinion piece.

While most university and college campus newspapers in Canada are produced by student volunteers, the Ryersonian is unusual: the students doing the reporting, writing and editing are part of a final year course for credit. It’s a model sometimes called a “teaching hospital” — students producing real stories for real audiences to gain near-professional experience that helps them “achieve the final stage of readiness” for their careers.

While two instructors (and two teaching assistants) coach and guide the final-year undergraduate and graduate journalists in editorial decision-making and production teamwork, the students staff ‘the desk’ (editor positions) and are engaged in decisions about what runs and what doesn’t. These discussions are critical to the ‘classroom learning’ experience. Occasionally, a thorny legal or ethical question prompts the teaching team to consult the publisher. The Ryersonian is published by the School of Journalism, which means the chair is the publisher. That’s me.

However, I usually see Ryersonian stories like every other reader — when they are uploaded. I don’t know what stories are pitched or being chased and I don’t get a preview, even if they involve Ryerson University’s administrative leaders. It’s critical that editorial decisions made in the newsroom are separate from decisions made in the business office in order to ensure the public is served journalism untainted by the possible interests of the publisher.

In October, when the instructors received an opinion piece written by a Ryersonian reporter they saw some of it was critical of the Ryersonian and the school of journalism itself, based on the robust and sometimes painful discussions in the newsroom last fall. So, they made a rare visit to me.

This was an ethical issue; a potential conflict of interest. Putting the piece through the regular ‘Sonian editorial process could mean students and the teaching team would be handling and editing a piece about themselves. At the same time, the Ryersonian believes fiercely in freedom of expression as long as writers’ opinions are acceptable, legally and ethically.

had to erect a firewall between the publisher, the instructors and the editorial process to protect editorial integrity. So, for the first time in memory, I hired an external handling editor for the Ryersonian, a journalist outside of the university who worked with the writer from draft to draft in shaping the editorial direction and writing. This approach does not lend itself to a quick turnaround, and it is more common in magazine publishing. For instance, it is the same process we employ for every feature story in the school’s other student-run publication, the Ryerson Review of Journalism.

The next step is copy editing: although I had an inkling about the focus of the story, since Deepak had conducted an interview with me in my role as chair of the RSJ, I have remained on my side of the wall, as have the instructors. So, we hired an experienced journalist to do copy editing (she had also worked as a Teaching Assistant in the Ryersonian) and I appointed a delegate publisher — my predecessor, Ivor Shapiro — to be the final eyes on the piece.

It is our responsibility to you, readers, and to the public, to assure you we have gone to unusual lengths to ensure there was no actual or perceived conflicts of interest in a story that may well make us uncomfortable.

— Janice Neil, chair, School of Journalism and Publisher, The Ryersonian.ca

(an earlier version contained an error about the age of The Ryersonian.)

This article may have been created with the use of AI tools such as