The COVID-19 pandemic has robbed students of so much. How can grief literacy help students who are mourning a sense of normalcy and family members?

Blanche Clemente misses the light coming through the windows of the Ryerson Student Learning Centre on Yonge Street. She remembers the free ice cream, Thai tea and pizza she and her friends would get on campus as they passed by the tents erected by various student groups.

In 2019, the fourth-year marketing co-op student made the Ted Rogers School of Management dean’s list. Between a full course load, working a part-time job, mentoring first-year students and living downtown with three roommates, the 22-year-old says life on campus kept her involved and content.

“I used to have a completely different life prior to COVID-19 and a lot of things have changed for me,” Clemente says, adding that she’s now living in Mississauga, Ont. with her parents, two brothers and two dogs. “I’m still not used to it even a year later.”

The shift to virtual learning hasn’t been easy for her, so she’s opted to take fewer courses and focus instead on just getting by. “The student in me has died … (online learning) is just not a substitute. I don’t think it’ll make up for the experiences I had on campus.”

Like many other students, Clemente is dealing with the loss of in-person classes, job opportunities, community, and daily interactions, among other things. Grief is typically associated with the loss of a loved one, but the COVID-19 pandemic has also robbed students of their university experience — a particularly formative time in someone’s life. And though students are grieving, experts worry the absence of grief literacy or grief-specific support may leave them without the necessary resources or language to identify these emotions.

“Grief literacy is really just helping people understand what grief is and also how to navigate grief in healthy ways,” says Andrea Warnick, a registered psychotherapist and a member of the Canadian Grief Alliance.

She says grief is something people need to talk about more often, especially given the amount of loss experienced during the pandemic. “Grief is so much more complex and so much more consuming, often, than just being sad,” Warnick says, adding that grief, though painful, is a natural and healthy process.

Last summer, Clemente was able to access Ryerson’s student counselling services and her counsellor was able to help her identify her feelings as a sense of loss, allowing her to feel like her experiences were valid.

“I realized that I could be sad over what I missed, but also, accept that things (are) different now,” she says.

To better address the challenges caused by the pandemic, Ryerson’s Workplace Wellbeing Services partnered with the Centre of Student Development and Counselling to redevelop the Notice, Engage, Refer and Debrief training.

“The skills introduced in this training mirror those required for grief literacy,” Ryerson counsellor Jean Tsai said via email, “beginning with understanding contextual, systemic and individual factors that contribute to distress and responding with kindness, understanding and compassion.”

Though grief is a natural part of life, Tsai says it’s rare for an entire world to be experiencing significant loss at the same time. “The generational impact of this cannot be overstated.”

Feelings of grief extend far beyond the classroom and are not isolated to students. During the COVID-19 pandemic, people across the world have lost their jobs, financial stability, or have been unable to be at the bedside of a dying relative — sometimes all three at once.

The Canadian Grief Alliance has been pushing for the federal government to implement a national strategy to help people cope with loss. A portion of the $100 million the alliance is calling for in government funding would help spread public awareness and education on grief. Though the government is spending $240.5 million to expand virtual care resources and mental health supports, Warnick says grief is not a mental health condition, although it can develop into one if left unsupported.

“Most mental health organizations do not run grief programming,” she says. “You can have many people who work in mental health who are also grief illiterate.”

When coping with grief, the mechanisms people might have relied on prior to the pandemic — like travelling or gathering with loved ones to mourn a loss — have been less accessible, sometimes entirely unavailable.

Laura Farberman, a Toronto-based social worker and psychotherapist, says when emotions are not expressed in healthy ways, people can develop maladaptive coping mechanisms such as overworking, withdrawing, emotional eating or drug and alcohol dependence.

“Our old ways of coping might not be available to us. We’re forced to look inside,” she says. “But after a year everyone is sort of not wanting to pay attention to their faults anymore.”

Studies have linked grief and the stress caused by bereavement to physical health detriments. More than half of people who lost a friend or relationship experienced a loss of appetite, according to a 2019 WebMD survey. For those who experienced the death of a loved one, 63 per cent said they felt fatigued.

Farberman says feelings of sadness, anger, anxiety and loneliness are “thought of in the head, but felt in the body.” Additionally, when approaching someone who is grieving, the study found that saying “it could be worse,” did more harm than good.

The “it could be worse” mentality has been prevalent during the pandemic and Warnick says this is a characteristic of comparative suffering or comparative grief. “We are quick to put our own suffering on the back burner and be like ‘Well, at least I’m not the person dying in the bed right now’ (or) ‘Well, we’re not the person who went bankrupt,’” she says.

But people end up minimizing their difficult experiences and can experience disenfranchised grief, Warnick says, where an individual doesn’t acknowledge their experience as something worthy of mourning.

Being able to recognize one’s feelings of loss and put a name to it can be an important first step in the coping process. Author and psychiatrist Daniel Siegel coined the phrase “name it to tame it,” suggesting that by labelling our emotional experiences, we are somewhat able to manage them better and choose how to respond more adequately. By making space for these feelings when they arise, Warnick says, people might experience post-traumatic growth.

Warnick says the effects of grief may very well outlast society’s return to normalcy. “There’s no vaccine for grief,” she says, adding she hopes academic institutions don’t just assume it’s “business as usual” when in-person classes resume.

She hopes they “are conscious about creating recovery curriculums of sorts, which take into account all the loss that’s been experienced.” After all, Warnick says, for some students, their lives may never look the same as they did pre-pandemic because of the insurmountable losses they’ve experienced.

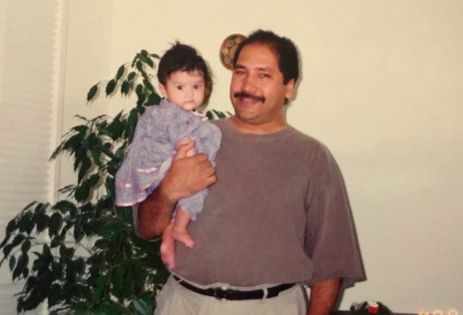

Last April, Helai Alikouzeh, a fourth-year bachelor of social work student at Ryerson University, sat on a chair beside her father in a Mississauga hospital. At that point it was her first time seeing her father in 20 days. He was admitted with COVID-19 around the same time the World Health Organization declared the coronavirus a pandemic — causing immediate closures and restrictions across Canada.

Her dad had already had open-heart surgery barely six months ago and Alikouzeh and her family had nursed him back to health. But when he was diagnosed with COVID-19, things took a turn for the worst.

“I had such high hopes,” she says.

It was painful to see her dad start slipping away again, but it wasn’t until her dad’s lungs and kidneys began to fail that she was able to convince the doctor to let her come see him.

And then, she says, “I watched my dad die.”

Alikouzeh says she was restless prior to her father’s death and she experienced a lot of anticipatory grief — a grief that happens when the death of a loved one is to be expected.

“I didn’t eat, sleep or drink properly,” she says. “I was running myself into the ground trying to research, find solutions and answer phone calls.”

The death of her father, Mohammad Hashem Alikouzeh, reverberated throughout the Afghan community. He had escaped the war in Afghanistan and come to Canada as a refugee. Along the way, Mohammad Hashem assisted many others, making friends across the globe and becoming a community leader in Toronto. During his admittance period in the hospital, Alikouzeh was updating concerned Afghans in the community, acting as a spokesperson, translator and daughter.

“I think somewhere along the lines, people forget that when somebody loses a parent, they all need to grieve,” she says, “and they also need time for themselves.”

Because gatherings of over 10 people were — and still are — prohibited, Mohammad Hashem’s funeral was live-streamed. Religiously, Afghan women aren’t permitted on the burial site and so Alikouzeh, her mom and her four sisters watched the service on their phones from outside the gates. Sometimes Alikouzeh will rewatch the recording of the service.

Reflecting on our relationships and experiences of loss can help with the grieving process, says Farberman, noting “our memories can help us move forward.”

Funeral homes have been doing their best to mitigate the impact of pandemic restrictions on mourners. Live-streaming ceremonies, drive-in services — where attendants sit in their vehicles and the service is broadcast on a transmitter — and pre-recorded eulogies are all examples of the creative ways funeral homes are trying to aid the grieving process.

Despite that, the inability to have a Fateya — or gathering of condolences — which typically happens a week after the burial, has hindered Alikouzeh’s grieving process and ability to find closure.

As she approaches the one-year mark of her father’s death, Alikouzeh self-soothes by reading about grief, sometimes even taking notes. Books she’s read like I can’t stop crying by John D. Martin and Frank D. Ferris or It’s OK that you’re not OK by Megan Devine have helped her better understand the sense of loss she’s experiencing.

One particular thing she’s read that has stuck out to her is the notion of people recounting their stories to others. “It’s not that they’re stuck in grief. They’re trying to process something that they went through and are in shock and in pain.”

Now in her final year of university, Alikouzeh is currently enrolled in six courses and says the leniency of teachers can assist in her healing process.

“I have to lean into … the support of my professor and lean into the support of other classmates,” she says.

Most of her professors have been understanding, but Alikouzeh says not all have extended the same grace.

“I need a safe space … without fully ripping (myself) apart.”

The pandemic might cause people to hold more reverence for ordinary moments, Warnick says, allowing for more gratitude in our lives. One thing to keep in mind, she says, is that our feelings are not static.

“There’s no absolute. You can be deeply grieving and have a lot of sorrow … and you can have joy and gratitude for things resuming,” she says. “They don’t cancel each other out. We can hold both of those realities.”

If you or someone you know is grieving and needs support you can contact the following:

Ryerson Centre for Student Development and Counselling

Facing Loss: Ryerson support group

Good2Talk: 24/7 confidential helpline for post-secondary students in Ontario which aids students with mental health, addiction and well-being.

BounceBack: free skill-building program managed by the Canadian Mental Health Association (CMHA). It is designed to help adults and youth 15+ manage low mood, mild to moderate depression and anxiety, stress or worry.