In high school, Reta found the rigid class structure and strong sense of community to be grounding. It allowed them to do fairly well academically.

The 20-year-old — who On The Record is only identifying by their first name due to worries about family finding out about their diagnosis — started at Ryerson in September as a first-year arts student.

Suddenly, they were in charge of staying on top of their deadlines independently. They lost the ability to socialize in person, making the shift even more isolating. It got to the point where they felt like they were “dying academically” and starting to miss their high school environment.

“I always felt like a fire would get set and I would be putting it out, and then another fire would be set,” Reta said. “Basically, I couldn’t manage my time.”

Reta always had a strong suspicion that they had attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) but last year, during a brief stint at Seneca College, they chalked it up to the usual post-secondary experience. The jarring experience of shifting to a university workload in an online learning environment pushed them to book an appointment at the university’s medical centre. Reta received a diagnosis in October.

Education experts say it’s been a challenge for students with ADHD to make the jump to online learning in an education system that is already not designed for students with a learning disability.

RELATED: Why compassion is key to making January’s return to in-person learning smooth

RELATED: Students, profs find the ‘silver lining’ in remote classes

With a return to campus imminent, the issue is even more prevalent, as students with ADHD, who have managed to adapt, face the challenges of reintegrating to in-person learning. Since research into the impact that remote learning has had on students with ADHD is an evolving topic, researchers say it’s still too soon to tell what the long-term effects will be — but they expect it’s going to have a significant impact.

“We’re still in the process of learning exactly what happened to students during the pandemic, and actively thinking, ‘What are the lessons that we can learn and take moving forward,’” said Ken Chatoor, senior researcher at Higher Education Quality Council of Ontario (HEQCO).

It’s not uncommon for online learning to make someone realize they have ADHD, said Annie Desrochers. She’s often the first point of contact as the resource navigator at the Centre for ADHD Awareness Canada (CADDAC).

“Many of the phone calls that I got of the post-secondary education students were students who did not know prior to [the pandemic] that they had ADHD,” she said. “All of a sudden, because of the change of the way they had to learn, it was made evident that they struggled.”

ADHD affects about three to five per cent of adults, according to CADDAC. It’s estimated that 1.1 million Canadian adults have ADHD.

Brittany Burek, a psychology PhD candidate at the Ontario Institute for Studies in Education, describes the process of searching and learning online as non-linear. Burek is currently studying topics relating to online learning comprehension for post-secondary students with learning and attention disorders.

She says students can go in all sorts of directions and end up down rabbit holes if they get distracted, especially when looking at a screen that can both entertain and teach.

“For neurodiverse students, there’s a greater chance of that happening more often and/or it being more impairing,” Burek said.

Figuring out strategies for staying on task is all about knowing your individual strengths and weaknesses, especially for students who made the jump to an environment dependent on self-regulated learning, said Burek.

Being online gives students access to great tools like spellcheck and bookmarking to find information easily. She recommends setting short timers just to get going on an assignment, talking with peers to increase clarity, and even creating a different profile on your computer for work and for play — suggestions students can carry with them when they make the switch back to in-person.

Although online learning has been a difficult adjustment for neurodiverse and neurotypical students alike, the distractions are more extreme for students with ADHD. They may have executive functioning challenges that impact behaviours like time management and prioritizing tasks, according to an ADDitude article.

Reta said learning online has been a learning experience in itself — but also a journey of growth.

In-person classes, which Reta had in high school, held Reta accountable because they would know a professor would be looking for their face and would feel guilty if they didn’t go. With online recorded lectures, it was a different story.

“I would rather bite off my own fingers than watch it on my own time,” they said. “There doesn’t seem to be any sense of reason to do it, even though I know logically I should.”

Reta said they’re a little scared when it comes to getting back into an in-person routine. They wonder whether in-person delivery will be as beneficial as they think. After all, Reta knows that online learning has its upsides and downsides, and the pressure to perform will make a campus return a little more stressful.

“I’m an undeclared [major], so right now is a very pivotal time,” they said. “I have to keep my GPA up if I want to apply to specific majors.”

Cher — a Ryerson student who is only being identified by her first name out of fear her diagnosis might impact her employability — had a terrible online learning experience. Once the pandemic hit, she had to set up her own at-home workspace, which came filled with distractions. Family intrusions, friend intrusions, and easy access to kitchen snacks made breaking focus all too easy. Once that happened, it was hard to get back on track.

Cher said she was able to find a good working rhythm following her ADHD diagnosis three years ago, thanks to studying in the Student Learning Centre. Seeing other people working helped motivate her.

“You miss everything,” Cher said of the virtual shift. “You miss going to campus, you miss interacting with your peers, you miss seeing your professor and looking at them, and taking notes as they speak to you.”

To combat getting distracted, Cher finds it useful to keep visual reference of her tasks by writing them down. She estimates how long each task would take, and checks them off her list as she completes them.

“I always felt like a fire would get set and I would be putting it out, and then another fire would be set.”

Reta, student with ADHD

Reta uses note-taking as a strategy to keep themselves on track. But they also stress the importance of staying engaged with other students — be it on Discord or a WhatsApp group chat. It’s a way not to feel so alone, they said.

Robyn Stephens, a clinical neuropsychologist and assistant professor in psychiatry at the University of Toronto, worries about the social and emotional development that students with ADHD have been missing out on for nearly two years.

People with ADHD typically have a disconnect between intellectual maturity and emotional and social maturity, Stephens explained. While their intellectual maturity and abilities are often well-developed, their emotional and social maturity has been clinically found to lag behind by a year or two. The lag eventually catches up, she said — sometime before a person’s mid-20s.

“Now they’re going back into the classroom…potentially three or four years emotionally and socially behind their peers,” Stephens said. “There’s a lot of work that’s going to need to be done on helping these students learn and develop their social and emotional coping skills and interactive skills.”

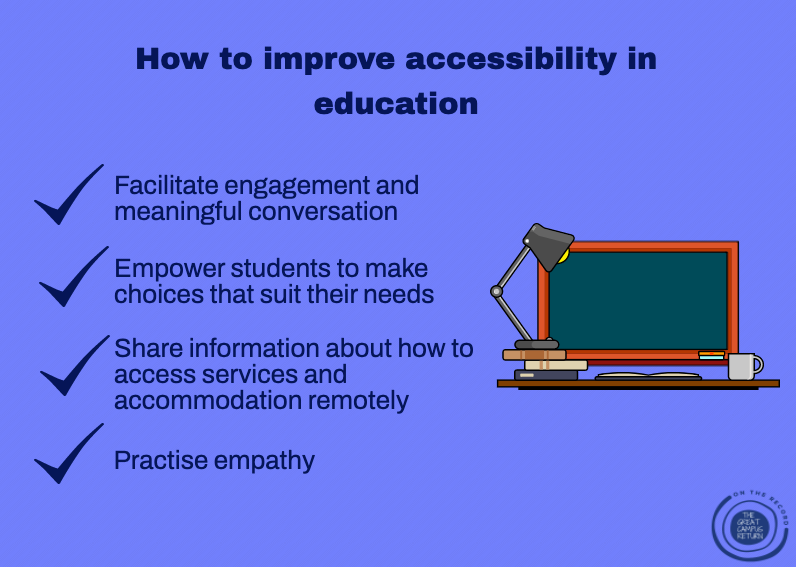

HEQCO’s 2020 study on lessons and recommendations for remote learning stresses that post-secondary schools should keep some tools in mind when moving into the winter semester.

“A big part of it will be giving people options and keeping those options that were there during the pandemic that worked for people. Make sure that they’re still available to people as you move forward,” said Chatoor, the HEQCO researcher.

Thanks to the Neurodiverse Students’ Association created earlier this year, Reta and Cher said they were able to connect with other neurodiverse students for a sense of community they’ve long been craving.

“There’s a little bit of increased compassion and understanding,” Reta said. “I love that because you don’t always get that sort of understanding from a group.”

RELATED: More online therapy key to dealing with growing demands for mental health counselling

RELATED: Amid worsening mental health, students are anxious to return to in-person classes

Simone Gavros was the Health Reporter for the Fall 2021 semester.