It was presentation day for a group of second-year undergraduate Ryerson students in Robert Osborne’s Age of Spin class. After clicking play, a set of videos appeared across 120 Zoom screens.

The first two videos seemed to capture Tom Cruise stumbling in a room, telling stories about meeting the former Russian president Mikhail Gorbachev and playing golf. In the third video, which was a close-up, Cruise says, “It’s the real thing.” He laughs, moves his right hand in front of his face as if pointing to it, and says again, “It’s all the real thing.” It’s not.

The class, which covers media manipulation, has just witnessed a popular deepfake video of Cruise’s face on another person’s body. This video was a testament that the world had moved from an age of spin to an age of fakes.

Information manipulation is a tale as old as time, evolving according to available resources. It started as people chiselling away at statues, metamorphosed into altering painted portraits, and, over time, digital alteration began.

As photoshop and spin news became more prevalent, the only remaining trustworthy avenue of information was video footage. That changed in 2017 when fake non-consensual pornographic videos were released by a Reddit account under the name “Deepfakes.”

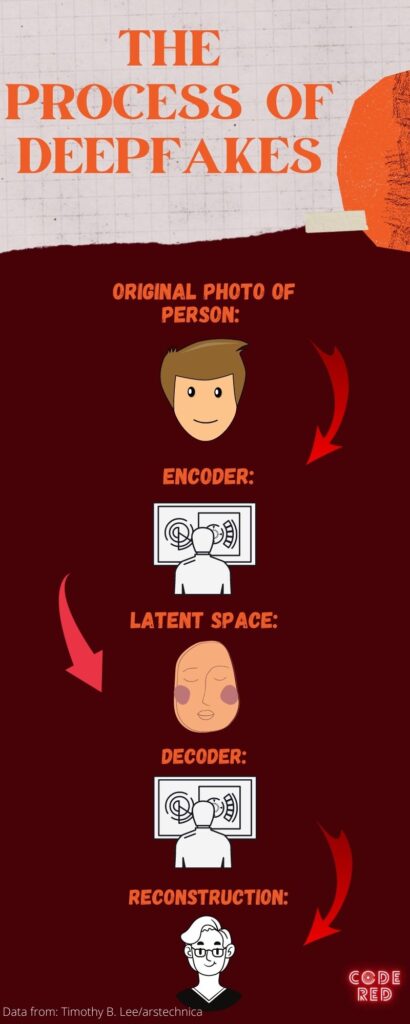

Artificial intelligence news platform, Unite, describes deepfakes as video and audio clips that transpose the face or voice of a person onto the body of another. The producer can visualize and create any fictional event in whatever setting they choose.

According to a study by Ryerson University’s Audience Lab, 71 per cent of Canadians go to YouTube as their first source when they want to learn anything. The Canadian Centre for Cyber Security’s website states that deepfake technology “used by cyber threat actors to create false or misleading online content has become cheaper and easier to access.” In other words, seeing is no longer believing.

The initial video manipulation technology was created in the 1990s by researchers. According to an Interval Research Corp. study, the earliest landmark project in the field was the Video Rewrite program in 1997, in which a video was dubbed with audio from a different track. The technology progressed over time, in parallel with computer systems growth. But it was controlled by researchers and high-end VFX labs.

Fast forward 20 years when, along with falsified pornographic videos on Reddit, came an open source code for face-swapping technology.

Jae Duk Seo, AI project lead at Ryerson University, said, “When we first played around with it, the results would clearly tell if the videos were deepfake or not.” Now, he says, “If an individual just knows the basics, a little bit of software knowledge, they can use (deepfake technology) and the results are phenomenal.”

The machine/deep-learning lead at a major VFX lab, Vinh Nguyen, says the technology is at a point where experts and software can detect 95 per cent of deepfakes, but the common audience can not.

Deepfake artist and researcher, Jan Fischer says, “Some of the really good tools are not publicly available. A limiting factor is the hardware and the cost of GPU usage in the cloud to create really realistic high-resolution fakes.”

In terms of video quality and cost, the market is very wide. Fischer explained how price usually depends on the length, required quality and the degree of complexity of a scene — like angles and lighting conditions — as well as other factors like data collection.

“You can get a simple, low-resolution clip for less than 100 U.S. dollars. Professional footage or production for movies quickly cost more than 10,000 U.S. dollars,” he said.

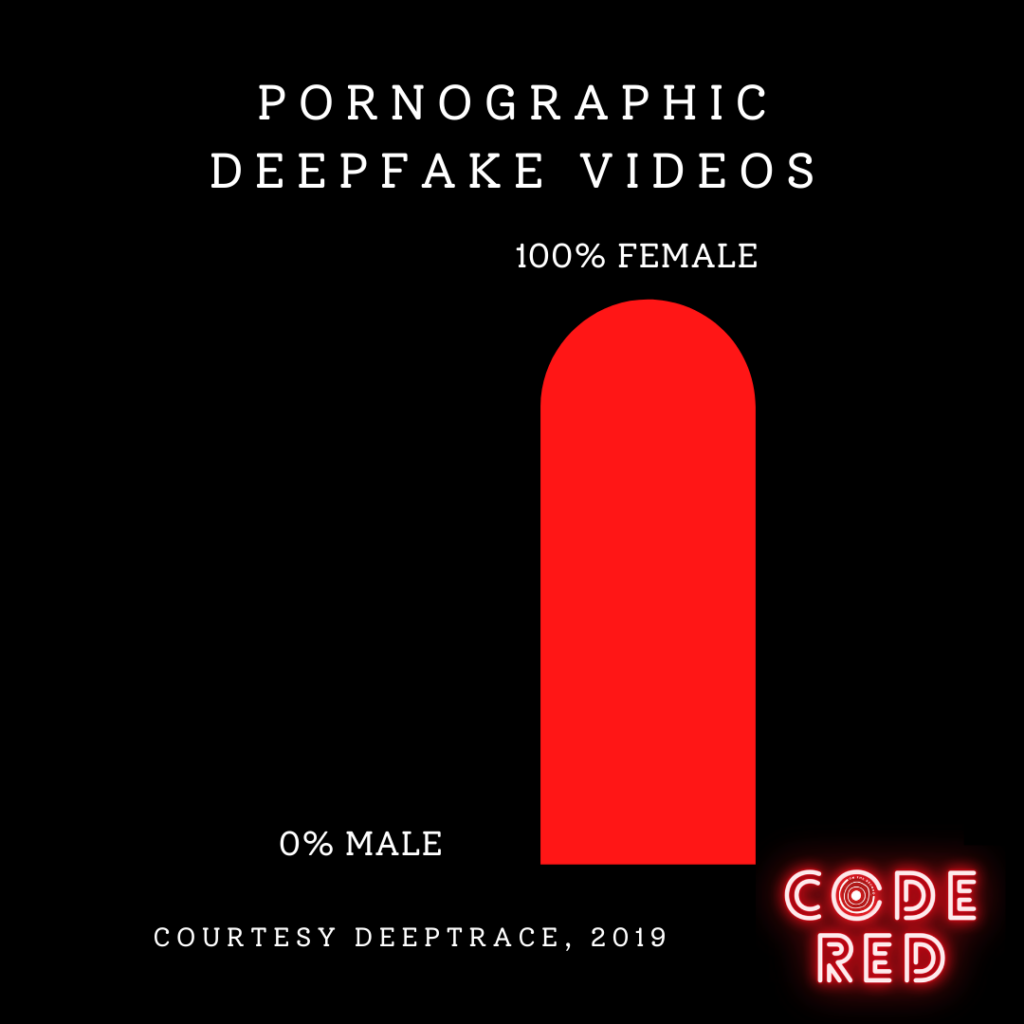

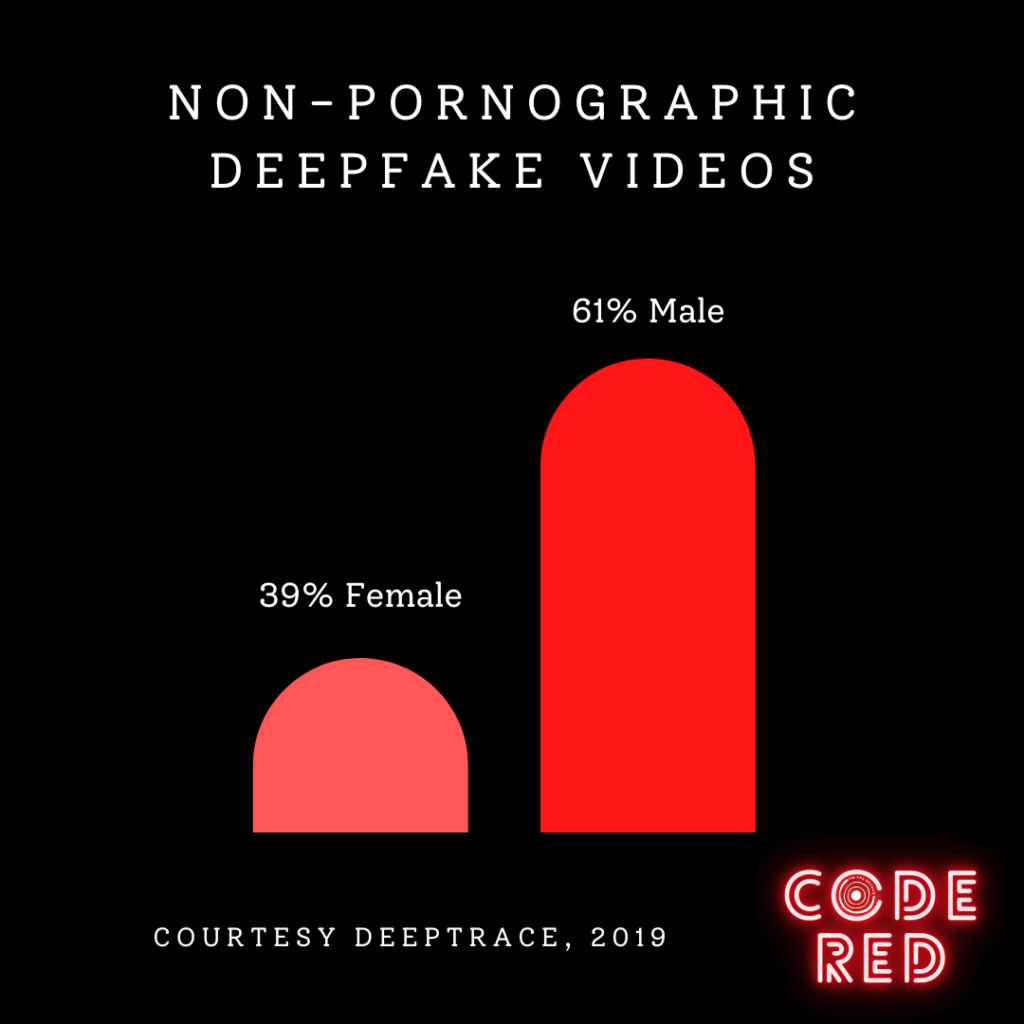

A study by the AI company, Sensity, revealed that 96 per cent of the deepfake videos circulating the sphere were pornographic and 100 per cent of these featured women only.

Britt Paris, AI and deepfake researcher said, “The use of this technology against common women like you and I is the area where these advancements are really problematic I think.”

According to a study by VAW, by the end of July, over 100,000 women had fake nudes — commonly called DeepNudes — posted on Telegram (a text messaging phone application). And this number is doubling every six months. By the summer of 2022, there are expected to be over 720,000 DeepNudes online.

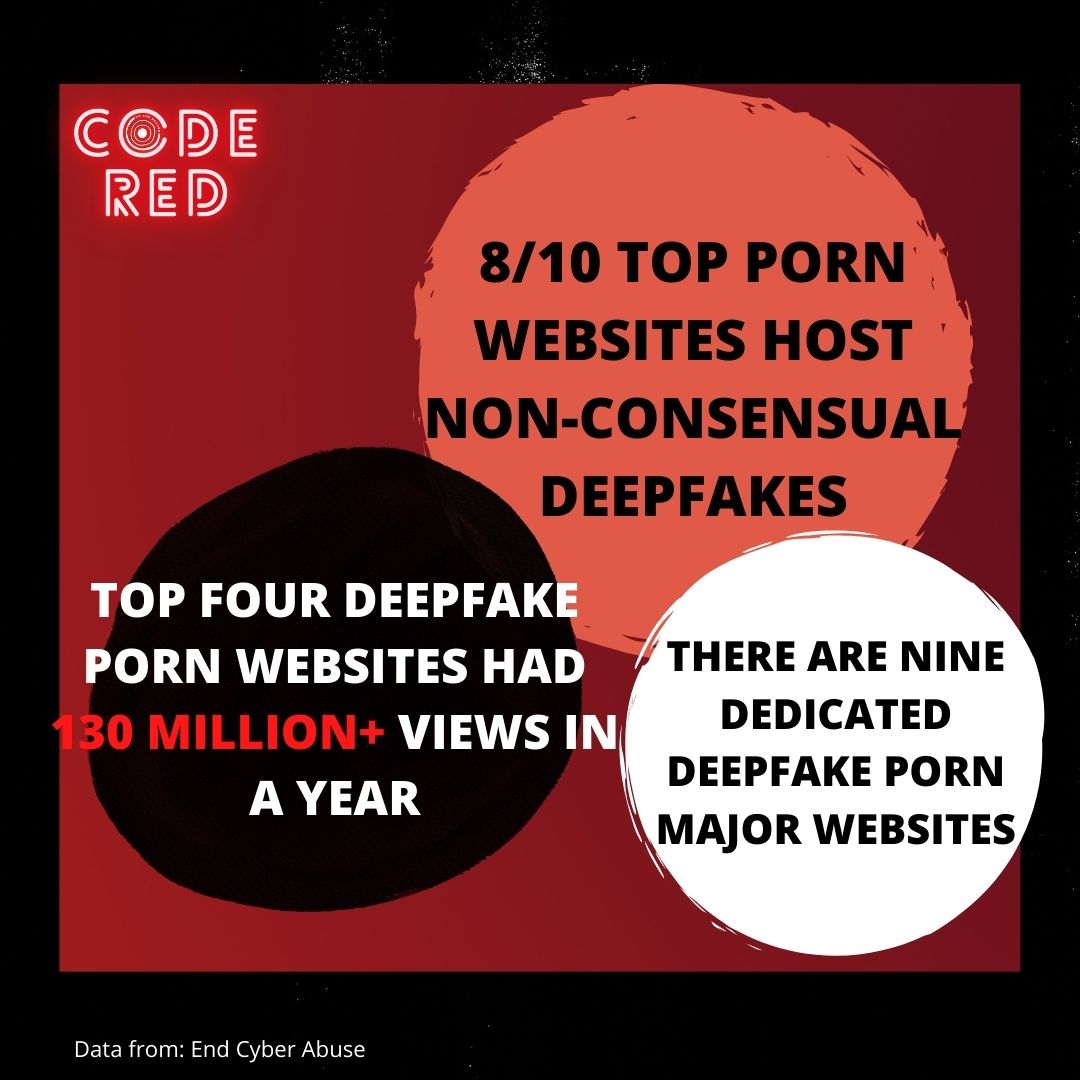

Technology-based sexual violence researcher, Vasileia Karasavva said that within a span of two years, from 2017 to 2019, the top four deepfake pornography websites had garnered more than 130 million views in one year.” With its increasing sophistication and ease of access, we “have to consider their weaponization for the perpetration of technology-facilitated sexual violence.”

This refers to the creation, distribution, or threat of distribution of sexual images or videos, she explained. The most widely known form of its circulation is revenge porn. “You can easily see how following the breakdown of a relationship, a disgruntled ex-partner could create a deepfaked pornographic video of their ex,” said Karasavva.

When it comes to the effects deepfake pornography has on women, the negative impacts on mental health do not come alone. It comes with the potential loss of job, university or college admissions, social relations and other opportunities.

Anita Sarkeesian is a Canadian-American critic of the objectification of women in video games. She was targeted with sexual deepfakes and people who did not like her criticisms cheered it on online platforms.

“Deepfakes are used as a weapon to silence women, degrade women, show power over women, reducing us to sex objects. This isn’t just a fun-and-games thing. This can destroy lives,” said Sarkeesian in an interview with the Washington Post.

Actor Scarlett Johansson, who has been subjected to DeepNudes said, according to the Washington Post, that celebrities like herself are “protected by their fame,” while women of lesser prominence get their reputations damaged.

Paris agrees. She said that public figures often have more resources to challenge this material in courts and to file injunctions and takedowns. “Who ends up being sort of harmed the most are these common people, classmates, ex-girlfriends, ex-wives,” she said.

What makes this scenario more destructive is the lack of legal and institutional protection. The paper, The Real Threat of Deepfake Pornography: A Review of Canadian Policy, by Karasavva and her peer Aalia Noorbhai, explores the recourse that Canadian legislation currently offers to victims of deepfaked pornography. “We find it very lacking,” Karasavva said.

Addressing the use of deepfakes in the political landscape, the Canadian Cyber Security Centre website states it has procedures in place to counter fraudulent attempts to imitate the Government of Canada online. Since March 2020, it has been working to take down more than 8,600 websites, social media accounts, and email servers impersonating the Government of Canada.” A legal amendment has also been passed which gives politicians protection from deepfakes. However, no such measure is in place to counter the 96 per cent of total deepfake content which is pornographic and non-political in nature.

“I think it shows the priorities of our legal systems that are based off the common law systems that are primarily in place to protect those who are already protected by the law and to ensure a status quo that works better for some people than it does for others,” Paris said.

Rida Khan/On The Record

Karasavva agrees that attention has been focused on laws for political protection. “I think these concerns are extremely valid. At the same time, I can’t overlook how deepfakes can revitalize technology-facilitated sexual violence,” she said, adding that includes delegitimizing female politicians.

Paris, while talking of the North American landscape, says that going to court is an option. Considering the current quality of technology being used against common people, forensics specialists can tell if a video is a deepfake. “But going to court takes a lot of money and takes a lot of time.”

Also, direct legislative protection still does not exist. The U.S. law has legal provision for revenge porn and that can be used for a portion of the cases.

Paris says right now, the best hope is to fight legal cases on clauses like defamation, violation of privacy, appropriation of personality, intentional infliction of mental suffering, harassment or human rights complaints.

“Even if you do go to court, there’s no guarantee that whatever piece of content you’re suing somebody over hasn’t migrated all across the internet.” With the ease and speed with which digital footage can spread, “it makes it very difficult to stop anything,” she said.

The spread can only be stopped at the source. Digital media platforms, for example, need to keep updating their counter technologies to stay on par with the quickly evolving deepfake software.

Nguyen said within a few years the technology will be advanced enough to produce undetectable fake content. He doesn’t think deepfakes can be fully regulated. He said that a possible solution his coworker came up with is to use blockchain or NFT technology. It is, he said, “a digital fingerprint, similar to diamonds with their GIA number inscribed deep in the diamond.”

Film producer Doug Daulton says from a creative point of view, the benefits of deepfakes are tremendous but so are the risks. “Deepfakes are simply too dangerous, particularly given how susceptible we are to lies,” he said. Those lies often spread through social media.

However, he says, “it is a legitimate art form as well,” and that it can benefit the film industry a lot. The quality, for the most part, is currently good enough for social media videos, but would not hold up on IMAX, 4K or 3D screens. So the use in the film industry is limited for now.

Fischer agrees, but adds that since the quality is improving at record speed, it will soon be good enough for extensive use in films as well.

Daulton advocates licensing. “There should be an FCC licence for VFX artists and houses producing deepfakes,” he said. Along with that, he notes the creator’s licence and production ID should be embedded in the end product.

According to Daulton, Microsoft, Google and Nvidia have made a working group to address deepfakes on their platforms.

Paris says Twitter and Facebook flag what they are able to catch as deepfakes. “They give a rundown and why they think it might be fake based on their algorithmic detection.”

Paris says that videos are now like any other information and need to be verified. “You can do a reverse image search, and you can see if other people are talking about this video that may be questionable… Check the source. It’s also important to check its proliferation through networks to see where it has been,” she said.

The source code is out there and the more people use it, the more bugs will be found and cleaned out, improving deepfake quality.

Deepfake hobbyist Miloslaw Olejnik says that times have changed and “there is no way back to being naive and [believing] all that you read and see.”

In Nguyen’s words: “Whether you participate in it or not, it’s coming and it’s coming faster than you think.”