With increasing income inequality, students have had to make difficult decisions regarding their careers

“Follow your dreams.”

You may have heard that powerful three word phrase many times in your life before. The promises of success and of cultivating a world where you can achieve whatever you set your mind to is enticing. If you work hard enough, you can do anything. But if you read between the lines, you will find one stipulation that comes attached to it: the need for money.

Shiva Kaami*, who would like to remain anonymous, knows exactly what happens to these dreams when the reality of one’s financial situation and personal responsibilities hits. As a young teenager engaged in his learning, he was eager to start university right after high school. That is, until his parents got divorced.

“Before I went to university, my parents divorced and my father stole my education savings plan,” he said.

Kaami’s plans to study business and social enterprises in university were ruined. The young adolescent was forced to go straight into the workforce to make up for the funds he was robbed of, first working at an electronic recycling company and then an office job.

“I was struggling with PTSD, depression and anxiety at the time,” he said. Now living in a single-parent household with his mother, Kaami said some of his income went toward the house expenses.

The median employment income of lone-parent families with one child was $36,400 in 2018, according to Statistics Canada. For lone-parent families with two children, the median income was $38,520. This number then dropped to $29,980 for families with three or more children. In a metropolitan city like Toronto, the cost of living is extremely high, forcing individuals at the lower end of the income bracket to be more realistic in their job prospects to make ends meet.

“One of the gateways to having a comfortable life is to have a post-secondary education,” said John Isbister, an economics professor at Ryerson University. Isbister said that the burden on students and their families is higher today compared to when he was in university back in the 1960s.

“You can’t even focus on your higher education completely because you have to work in order to make ends meet,” said Isbister. “Hardly anybody worked when I went to school in the ‘60s, because it (tuition) was so cheap.”

After a few years of being frugal with his earnings, Kaami had finally saved up enough money to pursue an environmental sciences degree, despite being interested in pursuing business.

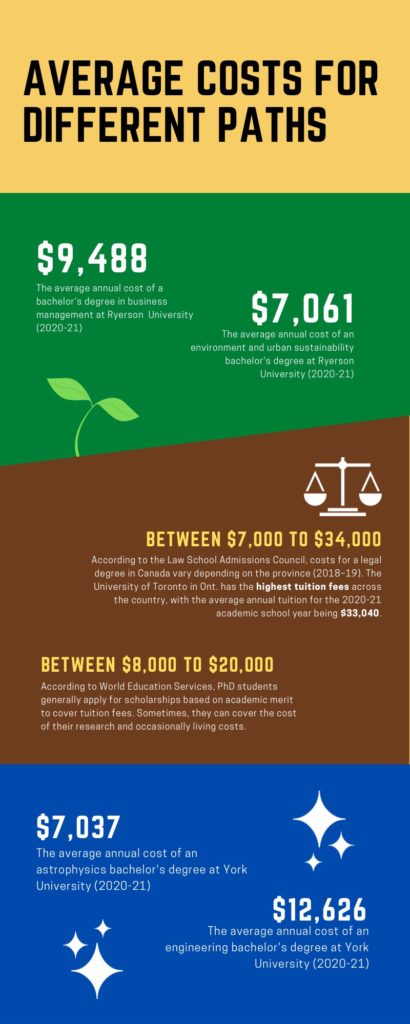

“The tuition was affordable and I loved education,” he said. “Business was way too expensive and having been a first generation student to attend university, I had no clue what to expect.”

At university, Kaami thrived. The academic environment was his chance to shine and engage in a place where he felt comfortable. He was a straight-A student, graduating summa cum laude, with the highest of honours. Throughout his four-year bachelor’s degree, Kaami worked hard — commuting for an hour and a half to get to class, working a part-time job, getting good grades and establishing relationships with his professors.

Through the obstacles he faced, Kaami managed to get to his fourth and final year. Confident in his abilities and skills, he mustered the courage to apply to Harvard University Law School — and he was accepted. But despite receiving such a prestigious acceptance to a top tier school, Kaami was forced to turn it down.

“At that time, I had to start taking care of my nephew,” he said. After his cousin’s wife lost custody of his nephew due to drug issues, Kaami’s cousin worked late nights, struggling to pay for his bills. To avoid having his nephew taken away by the Children’s Aid Society, Kaami and his mother had to step in to care for him.

With the decision to take in his nephew, Kaami was now responsible for another person in his life and his chances of going to Harvard were over — the tuition was just too high to afford. The 2020-2021 estimated budget for JD students at Harvard is roughly US$101,750 for just one year of study, according to the law school’s website. Converted to Canadian dollars, this would be over $125,000 a year.

Zahir Kolia is an assistant professor in the criminology department at Ryerson. Part of his work involves looking at how Indigenous and racialized communities are organized under settler colonial forms, a type of colonialism that displaces a territory’s original population with new settlers.

“There’s a global division, a racialized and gendered division of labor,” he said. “Racialized people in the so-called ‘Third World’ where many of our parents are from end up in careers like manufacturing goods for the West, where they’re basically cheap labour pools.”

Speaking from his family’s experience of being forced to flee from South Africa due to apartheid, Kolia’s inspiration to become a lawyer was partly due to finishing the degree his father never had a chance to complete, due to his difficult financial background.

Throughout his political science degree at the University of Toronto, Kolia often envisioned himself dressed in a suave suit and tie driving a nice car, walking into a wood-panelled room with a leather button couch, looking at papers.

But he soon came to realize that this fantasy was not as perfect as he envisioned it to be.

“Wanting to fulfil the lawyer fantasy was to speak back to the forms of dehumanization that I encountered (growing up),” he said. “As a young racialized person … I was fantasizing of exceeding all the expectations and the stereotypes that had been placed upon me.”

When faced with the decision of whether or not to go to law school, a professor who inspired him gave Kolia the outlook on one of two options: pursue law school, which would be a better move for his career, or pursue his master’s and a PhD program. The average salary of a lawyer in Toronto is roughly $89,000, according to PayScale Canada.

Wanting to work on the ground to reduce racialized forms of inequality, Kolia chose the latter, which led him to deal with financial hardships.

It took him seven years to get his PhD and his income during that time was roughly $10,000 a year. “I was going into an incredible amount of debt because I had to help out at home as well.”

After graduating, Kolia had to work as a part-time salesman, selling CAA memberships to people on the road. He recalls defending his dissertation while working odd jobs with first-year undergraduate students while he was trying to make ends meet. He found it challenging, as he was only able to get contract positions until finally gaining a full-time position at Ryerson in 2018.

“That was really difficult because I didn’t have benefits over the summer. It was really challenging working, just as hard as everyone in the department. But I was getting paid a fraction or a third of what they were getting,” he said.

Kolia did not move out of his mother’s home because he had to take care of her. Like Kaami, he wanted to leave Canada to attend school in the U.S. or England, but as a child of immigrant parents, he recognized there was a need to stay home and help provide for his mother.

The western norm of “moving out” is not common in ethnic households where there is an ingrained sense of responsibility toward taking care of the bills and their parents as they age. Similar to Kolia’s case, parents are typically not placed in long-term care homes and instead live with their children, in multigenerational homes. It builds a sense of belonging, community and family. According to Statistics Canada, there is a higher proportion of grandparents living in multigenerational homes among South Asians.

“I couldn’t leave home. There’s a difference in responsibility for children of immigrant parents,” Kolia says. “(Their parents) have really had to struggle and sacrifice, and there is a sense of responsibility that they feel towards (caring for) them,” Kolia said.

In an ideal world, Rebecka Mulders would have been an astrophysicist. She loved to learn and loved all things science. The present-day mortgage administrator was at the top of all her AP classes in high school.

But when she reached her senior year in 2008, she felt hopeless and depressed. “You want a future for yourself, especially as a teenager. They’re very hopeful for the future, they have great imaginations and big dreams,” she said. “But it wasn’t accessible for me, so it was like shutting myself down.”

After Mulder’s parents divorced when she was just a teen, she and her father, an engineer who did independent contract work, lived in their home along with multiple other renters just to make ends meet. Already aware of her precarious financial situation, Mulder stayed with her father for a year and then moved out soon after. “There was encouragement to go (to university) but there wasn’t any financial support to go,” she said.

Mulder never ended up getting a degree. Instead, she went into the trades, working job to job to support herself. She worked in retail first, before becoming a life insurance agent. Then came bookkeeping jobs until she finally landed her current job at a trust company.

“It was purely about who was hiring, getting some work experience here and there,” she said. “Opportunities presented themselves in a way as though the world had room for me to fit in there and that’s where I ended up.”

According to a 2017 census by Statistics Canada, women with a bachelor’s degree earned more money than those with college, high school or trades education. Their median annual earnings average to about $68,000, while women with a high school diploma, apprenticeship certification and/or college diploma earned a maximum of around $48,000.

Mulder finds it difficult to think about what she could have become, had her financial situation not prevented her from accessing further education.

“I would become a lifetime academic. I would just never stop learning,” she said. “It is such a big fantasy for me that I don’t let myself go there, I don’t even picture what I would have done.”

Kaami now works at a Canadian non-profit organization in Toronto. He is able to engage in his environmental advocacy through his job. “I’m quite happy. Content,” Kaami said.

The one thing he wished he didn’t miss out on, though, was his chance to have a social and love life after constantly being forced to work all the time. He struggles to find like-minded people of his age group and finds that it continues to get harder with age. “My advice is, no matter how busy you are, take at least a little bit of time each week to go do social stuff,” he said.

Nonetheless, Kaami still has big plans for his future. Although he lives at home with his mom and nephew, he plans on looking into pursuing an MBA. “An MBA is super useful for all fields,” he said.

Pursuing a Master of Business Administration (MBA) comes with advantages and disadvantages. The Harvard Business Review reports that an MBA degree focuses on teaching students about building leadership skills and learning business principles. These degrees can be useful to expand one’s professional networks into new industries and increase opportunities for obtaining jobs with higher salaries. In fact, the average total salary of an MBA graduate from the University of Toronto’s Rotman School of Management in 2017 to 2018 was $120,874.

But to get to this stage is still a costly endeavour, with tuition fees ranging from $3,600 at the Université du Québec à Montréal to $103,008 a year at the University of Toronto’s Rotman School of Management, according to Maclean’s Magazine’s study of MBA tuition rates in 2016.

Regardless of the educational degree one chooses to pursue, students are undoubtedly left to deal with significant financial burdens in order to achieve their dreams.

This story was updated on Mar.15, 2021, at 5:15 p.m. EST. In an earlier version, it was incorrectly reported that Zahir Kolia took nine years to complete his PhD. That should have read seven years.

This article may have been created with the use of AI tools such as