Politicians and advocates across the province are decrying the Ontario government’s attempt to block municipalities from pursuing ranked ballot elections, calling it the latest example of provincial meddling in municipal affairs.

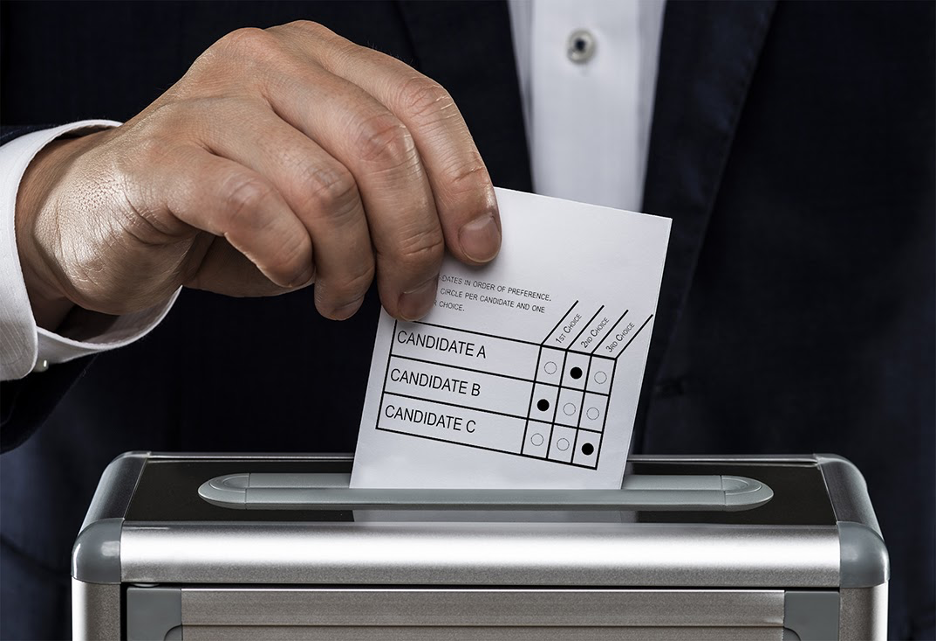

The Ranked Ballot Initiative of Toronto (RaBIT) has been gaining traction in Toronto, with the city looking to implement ranked ballots in the 2026 municipal election. Mayor John Tory and several city councillors voiced support for the proposed reform.

But last week, Doug Ford’s government introduced a COVID-19 bill with a measure that would stop municipalities from using ranked ballots. That legislation would undo a 2016 Wynne government amendment to the Municipal Elections Act which allowed municipalities to institute the practice. Ranked ballots were used for the first time in Canada in London, Ont.’s 2018 municipal elections.

Myer Siemiatycki,a professor emeritus in urban politics at Ryerson University, said lumping pandemic control with city elections doesn’t add up.

“Outlawing ranked ballots in municipal elections in a bill presumably about COVID kind of tells you something smells here,” Siemiatycki said. “These two things don’t fit together.”

A press release from the office of the Municipal Affairs and Housing Minister stated the government is “maintaining predictability, and consistency for municipal elections, while better respecting taxpayers’ dollars.”

Siemiatycki said Ford’s repeated interference in Toronto elections might be personal. Ford previously made the abrupt decision of slashing Toronto city council nearly in half three weeks ahead of the 2018 municipal election.

“In the sphere of municipal politics, (Ford) appears to have kind of a particular vendetta, settling scores, that he feels the need to inflict on the City of Toronto in particular,” Siemiatycki said. “It’s almost like he begrudges the city that he was not elected mayor.”

Ford is not the first premier to interfere in Toronto’s affairs. In 2017, former premier Kathleen Wynne vetoed newly introduced tolls on the Don Valley Parkway and Gardiner Expressway. At the time, Tory responded by telling reporters it was “time that we stop being treated, and I stop being treated, as a little boy going up to Queen’s Park in short pants to say, ‘Please, could you help me out with something that I thought was in the City of Toronto Act that I could do?’ ”

Right now, provinces have complete constitutional authority over municipalities. The Ontario Court of Appeal affirmed as much in 2018, when it upheld the cuts to city council. Toronto recently received leave to appeal that decision to the Supreme Court of Canada.

Without strengthening the autonomy of municipalities, local democracies could be completely trampled over, Siemiatycki warned. “Unless some limits are put on provinces’ abilities to intervene in municipal governance processes, things could really start getting out of hand,” he said. “What would be next? The province overturning the result of a mayoralty race where they don’t like the mayor who got elected somewhere?”

Whether motivated by personal vendettas or political expediency, the question of how municipalities can stop provinces from interfering in locally-made decisions remains. For Toronto advocacy group Charter City Toronto, the answer lies in creating a city charter that is constitutionally recognized.

Beth Levy, a former candidate for Toronto city council and member of Charter City Toronto, said a charter would strengthen Toronto’s autonomy and allow the city to better fund its priorities.

“We’re the biggest city, we’re the most diverse city, and yet everything is a top-down approach and a one size-fits-all,” she said. “We’re shown time and again, that doesn’t work.”

To make Toronto a charter city, a constitutional amendment backed by the governments of both Ontario and Canada would need to be passed. The charter would protect the city from provincial interference on issues of municipal jurisdiction.

Levy recognized that this is unlikely to happen soon and said the process would first require extensive consultations with the public before a charter could be drafted.

Not everybody supports the charter city approach. Kristin Good, a political science professor at Dalhousie University, said passing a city charter would complicate decision-making on issues that affect more than one municipality.

“I’m against (it) because, in some cases, there could be a broader provincial interest or metropolitan interest in having a province impose a solution for a city,” she said.

Good favours mechanisms which would limit the province’s ability to interfere in issues of municipal jurisdiction. “You can introduce provisions that, if you’re going to change, say the Municipal Elections Act, the Ontario parliament would have to get a two-thirds majority vote to make those changes in the future, which would protect municipal autonomy in that area,” she said.

While such reform is unlikely with the current Ontario government, Good believes a future government may be interested in granting municipalities more autonomy on issues that are solely of municipal interest.

“You just need a government that has some respect for local democracy and [wants] to be part of democratic reform,” Good said.