Post-secondary students and young adults come across more misinformation than the general population in Canada, according to a report by the Cybersecure Policy Exchange (CPE).

The report found that Canadians aged 18 to 29 reported seeing about 25 per cent more deliberately false information than the rest of the population.

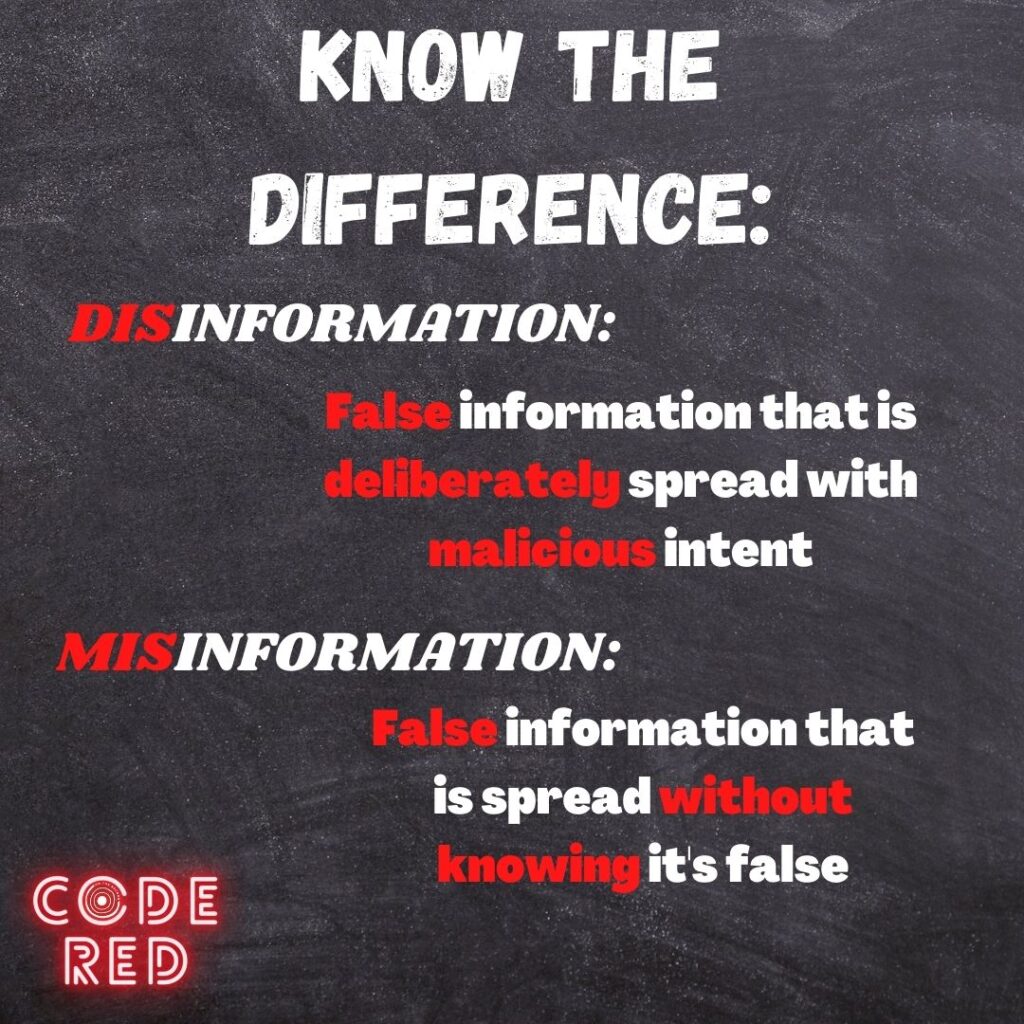

Over the last six years, misinformation has become increasingly volatile in today’s social climate, cultivated in part by the spread of so-called “fake news” during Donald Trump’s presidency. Misleading and flat-out false information about topics like COVID-19 and vaccines have become widespread, leading to protests and harmful demonstrations across the country — including in Toronto.

The issue is especially pertinent after news about Frances Haugen — the latest Facebook whistleblower — recently made headlines, once again bringing misinformation into the spotlight.

Haugen alleges the tech giant chose profits over consumer safety, knowingly amplifying things like hate and misinformation in order to grow its own reach.

James Turk, director of the Centre for Free Expression (CFE), echoes the sentiment.

“The business model of social media companies is inherently designed to spread information that will keep viewers’ eyes on their screens because social media companies need to sell users’ information to advertisers,” said Turk.

Through the CFE, which runs in conjunction with Ryerson University, Turk helps to educate people about topics like censorship, disinformation and students’ rights by providing resources to help navigate these issues.

While Facebook has started privately funded fact-checking initiatives in an attempt to help curb misinformation on the platform, critics like Turk argue that social media companies cannot be relied upon to monitor themselves.

“What draws people are excitable things, whether it be reports of murder or hyperbolic speech,” he said. ”The very business model creates the problem. And to think that they are the ones to save us from it is the biggest error any of us could make to address the challenge that we face.”

The Canadian government recently proposed legislation that would help curb so-called “online harms,” including content that incites hate, promotes violence and extremism or other illegal activity. While not entirely linked to misinformation, it’s seen by experts as a first step in a potential avenue to govern how dangerous content is dealt with online. Critics have already started to highlight how this legislation could negatively impact people’s human rights.

Given the potential faults of proposed governmental regulation, there’s also the possibility to teach younger generations about the issue so they’re more equipped to deal with it — although that may come with its own faults as well.

“Whatever we teach kids now in school … it’s going to be out of date by the time they need it,” said Sam Andrey, director of policy and research at the Ryerson Leadership Lab and the CPE.

Young people are more frequently relying on social media for information, and private messaging is also a major component in this shift. An earlier report published by the CPE showed those who used apps like WhatsApp, Facebook Messenger and Instagram Direct Messenger for news reported higher levels of seeing false information than the overall population. They saw misinformation at least a few times per week.

While the effectiveness of external regulatory bodies is debatable, experts suggest people keep a few things in mind when scrolling through their feeds. Start with developing so-called “digital hygiene practices,” said Anatoliy Gruzd, Social Media Lab director of research.

“Many news organizations were talking about personal hygiene practices: wash your hands, wear a mask to protect yourself from COVID-19,” Gruzd said. “The same can be said about misinformation to protect yourself from being tricked. You want to develop certain steps. When you get some information on a subject you’re not sure about, verify the information on credible sources first.”

Younger people have the benefit of having grown up surrounded by technology and social media, giving them somewhat of an advantage over older generations. But with the rate at which misinformation continues to grow and spread, some argue no amount of tech prowess can save you if you’re not properly educated on the issue.

“In general, I think just about anybody who feels very confident in their ability to navigate the information environment and distinguish true between false — they’re not as good as they think they are,” said Craig Silverman, a reporter with ProPublica.

Silverman gained prominence over the last six years as a result of his coverage of misinformation while he was a media editor at BuzzFeed News. During his time with the news organization, he saw misinformation go from a niche topic that only a “handful of nerds in journalism” cared about to a globally discussed topic.

The issue turned from debunking “fake news” into having legitimate discussions about misinformation, he said — inside and outside of the newsroom. But with that development came changes to the seriousness of the issue, which was in part fostered by shifting consumption habits — especially in younger generations.

“For a very long time, the way people received news was through these gatekeepers: through television, through newspapers, through radio,” said Andrey, from the CPE. “Those are still really important vectors for a lot of people to get their news, but we’ve changed the way that all that gets distributed to people.”

Despite this, the rise of misinformation isn’t completely the result of advances in technology and easier access to information, according to disinformation journalist Ali Breland.

“People get overly techno-deterministic in assuming that the advent and proliferation of technology is the thing driving misinformation,” said Breland. “The other reason is people. The sort of general social economic situation has become more tenuous for so many people that they’re willing to believe information and be less scrupulous or buy into certain things.”

In Breland’s eyes, public discourse is one of the only concrete avenues for dealing with misinformation. As long as people are speaking openly with members of their community about controversial topics, he says there’s a chance to curb its spread.

Discrediting individuals who participate in conspiracy rhetoric and perpetuate disinformation is counterproductive, said Breland, adding: “It’s far better to treat them respectfully and to listen to their position. If you have questions about it, try to have a non-confrontational discussion about it. And try to lead them to consider alternative viewpoints.”

There’s a degree of uncertainty as to what the future of misinformation means. Whether the brunt of the work being done to address the problem belongs to private institutions, the government or individuals remains to be seen. But in the eyes of a veteran in the misinformation beat like Silverman, there’s still hope.

“I feel like we are actually getting to a more productive place in some ways,” said Silverman. “The discussion … is less focused on speech and ‘how do we stop people saying things that are untrue,’ and it’s more focused on, well, ‘how do we enforce transparency and accountability for these huge systems?’”