I can recall with muscle-constricting clarity the moment I found out the international travel ban had left me stranded on Ryerson University’s campus.

It was Friday, March 13, 2020. Ryerson’s bustling thoroughfares quickly emptied, their silence filled by the cacophony of ambulances wailing up Church Street.

For some students, the trip home for lockdown was a GO train away. For others, like me, it wasn’t so easy. I braced myself for a few weeks of total isolation as I waited for a tourist visa to allow me to return to my parents in Moscow, Russia.

I thought it would take a few weeks to return to my family. It took me eight months.

Nearly two years later, after I’ve adjusted to learning 7,480 kilometres from campus, Ryerson wants me and the rest of its 4,200 students scattered across the globe to return in a matter of weeks.

The problem is: I can’t.

LISTEN: What Ryerson isn’t telling us about the return to campus

WATCH: Ryerson unions raise COVID-19 safety concerns ahead of January campus return

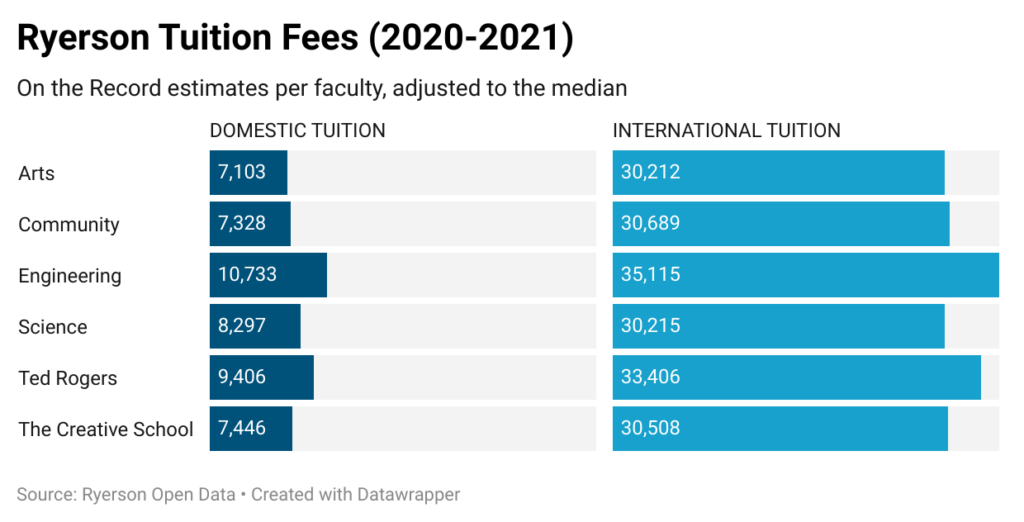

International students are a small but mighty Ryerson demographic. They make up nine per cent of the student body, but account for a large portion of university revenue. But with weeks to go before the university returns to in-person learning, students abroad are still in the dark about how they’re actually going to get back.

“One of our key priorities is to make sure we facilitate the safe return of our students who are abroad,” university president Mohamed Lachemi said on Nov. 15.

Yet the university has laid out a relatively restrictive return-to-campus plan that implies everyone — regardless of circumstance — will have to come back. First, they gradually increased campus activities, then they imposed a strict vaccine policy that limited students’ access to their timetables if they didn’t declare their vaccination status.

That restrictive plan feels especially fallible now as a new variant, omicron, has sparked closures around the globe — with Canada, in particular, restricting airfare from 14 African countries.

Whether it’s border closures or vaccine issues, the reality is that there are many complicated reasons why foreign students, or domestic students living abroad like me, can’t come back right away. So what does that mean for us?

The questions remain:

If borders close again and students can’t physically return, all while their instructors decide against offering online class materials, what will happen to my and my peers’ academic standing?

What kind of support does Ryerson plan to offer international students who are still displaced abroad?

Will failure to return affect their graduation timelines?

Will the International Student Support (ISS) office be able to accommodate every student who needs a vaccine, and how, exactly?

What happens to our education if Ryerson decides accommodating us is just too complicated?

IN PICTURES: How time and a pandemic have changed Ryerson’s campus

I took my questions straight to university spokesperson Jessica Leach. She wouldn’t elaborate beyond citing existing university press releases. She said the ISS office would answer my vaccine questions. But my requests to that office went unanswered.

Choosing to stay or go is a high-stakes decision, particularly for students who’ve spent nearly two years now creating new lives elsewhere. For me, that high-stakes decision is only intensified by my own lack of access to a Health Canada vaccine, and the fact that my own story of displacement as a domestic student is more complex.

Santiago, a third-year aerospace engineering student who is only being identified by his last name out of fear of academic repercussions, returned home to São Paulo at the start of the pandemic. He’s frustrated by the lack of university support, and the slowness of communication during a time when getting answers is critical.

He has sent repeated emails to ISS on the validity of his vaccine and other visa issues, but only ever hears back around a week later.

“So far, all the school has been committed to doing is their legal duty to track international students arriving in Canada, their quarantine plans and their vaccination status,” he said.

He said the school is “lacking a lot of communication.” One email update offered “no substantial information other than ‘contact your department to know if classes will be in person.’”

While he’s planned to come back to Toronto, he says the lack of a final decision on whether his faculty will hold classes in-person, is making him reconsider. Santiago adds he would prefer the option of a hybrid semester to give him enough time to move back to Canada properly, because none of the barriers blocking international students are easy, or quick, to move.

Bureaucratic demands on overseas students have only increased since the pandemic began. Aside from simply applying for a student visa, international students must present a temporary resident visa, an approval letter, and a COVID-19 readiness plan.

Between January and September this year, the Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada (IRCC) office says it received 406,000 study permit applications. That’s nearly 100,000 more than the previous year.

The sheer abundance of applications to process only adds to the time crunch. Processing times currently sit at 14 weeks for a student visa, according to their website. Students waiting to see if the university will pull the plug on its plan for a mass return to campus come January before they make arrangements to return, risk not arriving on campus in time.

Vaccination is another headache altogether. Not every country has access to Canadian-approved vaccines like Pfizer, Moderna, Johnson and Johnson and AstraZeneca. This means even more hurdles for international students — and they’re feeling the pressure.

Ryerson doesn’t consider me vaccinated, as I was inoculated last February with a vaccine shrouded in controversy: Sputnik V. While it’s performing well in clinical trials and recognized by 73 countries, Sputnik V isn’t recognized by the World Health Organization, EU Medicines or Health Canada.

How the winter semester unfolds depends largely on whether the university plans to accommodate the interests of international students. If they don’t, Ryerson risks abandoning international students in a time of crisis.

That’s made coming back a challenge, since Ryerson doesn’t consider me vaccinated. I risk access to my timetable and other Ryerson systems if I don’t comply by Dec. 15.

I have yet to receive access to another dose of a vaccine and can only hope hybrid options will be offered to students in my situation.

I’ve chosen not to return because there’s too much uncertainty and I’d be returning to a place where I don’t have a support system. That sacrifice is far too great during a pandemic.

After enduring a lockdown for over eight months on my own, without access to a single loved one outside of a screen, I’ve decided I’m never doing it again. I’m certain I wouldn’t survive it; my education can take the hit.

READ MORE:

- Amid worsening mental health, students are anxious to return to in-person classes

- Pandemic learning left students with ADHD behind. Here’s how a campus return could fix that

- Ryerson’s student groups prioritize making religion more relatable on campus

- More online therapy key to dealing with growing demands for mental health counselling