Although using artificial intelligence (AI) to create music is not entirely new, the design of the latest models and the rate at which they are being released is putting creativity in the industry at a crossroads, according to experts.

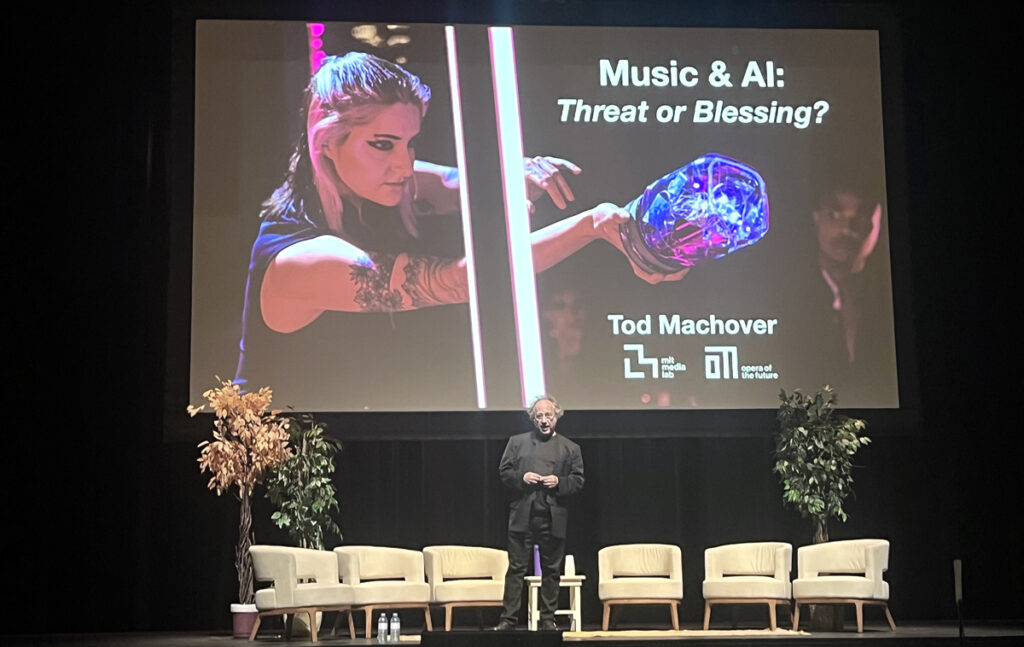

“I’d say that I really do think we’re kind of [a] fork in the road for how AI and music can develop,” said Tod Machover at the conclusion of his hour-long presentation for Music and AI: Threat or Blessing? He is the faculty director at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) Media Lab.

Machover spoke at The Creative School Chrysalis in one of a series of sessions in the week-long “Promise of Music” conference brought to TMU by the Glenn Gould Foundation.

“I think it’s kind of important for all of us involved in any field related to music to work on these issues now,” Machover said, “and it’s up to us to influence [AI] in a positive way.”

How is AI used in the music industry right now?

60 million people used AI software to create music in 2024, according to the International Music Summit (IMS) report released this April. 10 per cent of consumers IMS surveyed also said to have used generative AI systems to create lyrics. At his talk, Machover mentioned Velvet Sundown, the AI-generated band that a few months ago went viral after 1 million streams on Spotify. He played a snippet of one of their tracks to the event’s audience, describing how he found it both “generic” and “kind of dystopic.”

In his presentation, Machover described AI systems that can create music or augment when it’s played. An example of the latter included how AI designs can be embedded into instruments, resulting in a “hyperinstrument” that enhances the musician’s performance, like Yo-Yo Ma’s ‘hyper’ cello.

“Most people abandoned the approach of trying to understand how [AI models] really work,” Machover said. “And the AI that exists now… resulting in, like, a new company almost every week, is based on this kind of pattern matching,” rather than “understanding what’s going on.”

The most popular of these companies, mentioned in Machover’s presentation, is Suno AI. The Boston-based start-up works like ChatGPT: users can prompt Suno to generate a song “about the Sunday Scaries” or “about the dentist,” and it will spit it out quickly.

Suno AI, along with another business called Udio, have been facing lawsuits from Universal Music Group, Warner Music Group and Sony Music over copyright infringement. These industry giants accuse Suno and Udio of training their models with non-licensed tracks.

But other experts note that AI tools have been used in other aspects of the business side of the music industry, from planning venue bookings to creating promotional materials.

Just this week, Taylor Swift has received backlash from her fans for allegedly using AI tools in the creation of promo videos to her latest album “The Life of Showgirl,” released on Oct. 3. Some fans, using the hashtag #SwiftiesAgainstAI, have gone so far to accuse her of being hypocritical given that the artist has been an outspoken critic of AI tools for creating deepfakes of her before.

“There’s a lot of unresolved detail and unresolved clarity about whether or not an artistic creation made by using generative AI only can be copyrighted or not,” said Catherine Moore, professor of music technology and digital media at the University of Toronto. “But [for] music creators, that’s a big concern of how they’re competing now,” since “the early versions of these systems were pretty bad.”

How will AI reshape the music industry?

Julian Grande, a fourth-year professional music student at TMU, said that he finds AI tools to be a blessing for music because “now we’re forced to lean into things that only humans can do.”

“That’s where I think AI won’t bridge that gap, because it’s not a person, right? It doesn’t know what sore fingers feel like after playing a guitar [or] what fatigue feels like from playing drums.”

Moore said that, from the business angle, considering how streaming services might adapt is important.

“Could you say [as a streaming platform] we’re gonna make a difference in the price point that if you want only AI-generated music, it’s X, and if you want human-generated music, it’s X plus something,” she said. “That would be a scenario… because once there’s price differentiation, a lot of people make [purchasing] based on price.”

She also noted that as we enter music award season, committees like Juno and the Grammys are already starting to consider the threshold of how much generative AI assistance a song can have to be eligible for an award. “Only humans are eligible to be nominated” for any award category, according to Juno’s website.

Machover’s presentation concluded with the call to make these AI models “open-ended” and more able to be personalized, which he says will help us change them and understand how they work.

The deadline to act, he said, is approximately within the next three years.

“I don’t want to be glib and say that it’s easy for anybody to go out there and make a system customized to what they want to do,” Machover said, “but it’s not impossible, and it’s getting easier. And I want to inspire people to know that it’s worth giving it a try.”

Mariela Torroba Hennigen is a second-year Masters of Journalism student and a reporter for On The Record, fall 2025.

Otter.ai for generating transcripts for interviews. ChatGPT was used as a search engine to find sources to speak to, like Catherine Moore.