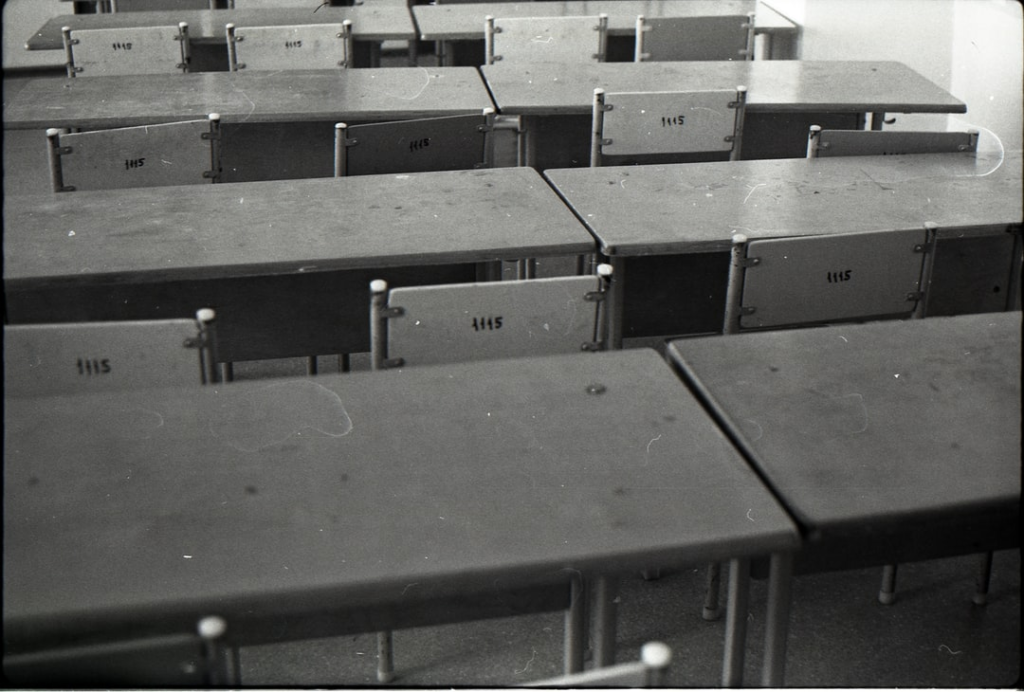

Isolation they experience in this system is a reflection of residential school system

Canada’s last residential school closed its doors in 1996. Over two decades later, Indigenous children in Canada are still feeling the effects of the country’s horrific residential school system.

In Canada, from 1831 to 1996, Métis, First Nations and Inuit children were taken from their homes and sent to over 130 residential schools across the land, according to The Canadian Encyclopedia. Indigenous families experienced intergenerational trauma as a result of the abuse that occurred at these schools. The Government of Canada funded these church-run schools in an effort to assimilate Indigenous children into Euro-Canadian culture.

“What residential school did was separate families,” Joanne Dallaire, Ryerson’s Indigenous Elder and senior adviser of Indigenous relations and reconciliation told the Ryersonian. “It began to plant the seed within Indigenous families, particularly children, that there was something wrong with them, that who they were wasn’t good enough and that they needed to forgo their traditional ways—the way that they have been raised—and embrace Christianity.”

The systemic inequities the residential schools contributed persisted long after their closure, as noted by a 2018 Ontario Human Rights Commission (OHRC) report. Indigenous children were placed mainly in non-Indigenous families for adoption or foster care by child welfare officials during the ’60s Scoop, which started in the 1950s and was another means of cultural genocide inflicted upon Indigenous communities and families.

“The monster that was created in the residential schools moved into a new house, and that monster now lives in the child welfare system,” said Sen. Murray Sinclair, chairman of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission on residential schools, during a national conference for child welfare held in 2018.

When residential schools were at the height of their use, they had fewer Indigenous children in attendance than the country’s child welfare system serves today.

In Canada, under 10 per cent of children are Indigenous, yet they represent over half of the children in foster care, according to the 2016 Canadian Census.

The state of the welfare system and Indigenous children is acknowledged as a “growing crisis” by the TRC. “Across Ontario, the proportion of Indigenous children in foster care is seven-and-a-half times what one would expect based on their representation in the child population,” according to a Statistics Canada figure cited in the OHRC report.

Future generations of Indigenous people who have attended residential schools have a greater chance of entering the child welfare system, post-doctoral fellow Brittany Barker told CBC News about her University of British Columbia research.

“The crux of the argument is that the family exposure to the residential school system is driving the overrepresentation of Indigenous kids in care,” said Barker.

Indigenous people are beyond twice as likely to be placed into care if their parents and/or grandparents attended residential schools, in comparison with those whose immediate family did not attend residential schools.

“If you look at the No. 1 reason that Indigenous youth are taken into the child welfare system, it’s for charges of neglect. And if you break down neglect, it’s parental substance abuse, it’s exposure to intimate partner violence, it’s housing instability, it’s food insecurity, it’s poverty – a lot of it is markers of poverty and then the remnants of the trauma of the residential school system,” said Barker.

The OHRC inquiry into 38 mainstream children’s aid societies (CASs) showed there was an overrepresentation of Indigenous children at 93 per cent of the 27 CASs from which the OHRC received sufficient information.

“Overall, the proportion of Indigenous children admitted into care was 2.6 times higher than their proportion in the child population,” the inquiry stated. The OHRC inquired about non-Indigenous mainstream CASs for the investigation, which partially attributes to the percentage of Indigenous children in welfare potentially being underestimated.

“This history of oppression and the continued discrimination that Indigenous peoples face today has led to multiple negative social and economic disadvantages, such as low levels of education, high levels of unemployment, extreme levels of poverty, inadequate housing and health disparities,” the OHRC inquiry said.

First Nations children living on reserves faced prejudice by the federal government through several interactions with child welfare structures, which was discovered by the Canadian Human Rights Tribunal in its 2016 verdict. Examples involved the federal government motivating the admittance of Indigenous children in welfare by allowing refunds of specific costs and insufficiently financing services for prevention.

The overrepresentation of Indigenous youth and children in the child welfare system is being addressed through the collaboration of academics and advocates, Indigenous and non-Indigenous, with The Action Group on Access to Justice (TAG) from the Law Society of Ontario.

According to TAG, the people they consulted with “also indicated that a lack of resources available to address the root causes of children in care, such as addiction and poverty, contributes to cycles of entire families in care across multiple generations.” Indigenous parents lose children to this system even though they would have been able to protect them at home if culturally appropriate aid was present and financed.

“Society decided that Indigenous people could not take care of their own, which may have been true, but they didn’t offer to help. They just took the children away, they further damaged the lineage of Indigenous people and kept continuously telling them that they were not deserving and not good enough,” Dallaire said.

Losing their sense of self and enduring extensive separation from their culture is one of the harmful consequences Indigenous youth and children undergo as a result of the child welfare system, according to consultation contributors of the TAG collaboration.

“You have kids coming out of residential school who are totally alienated, they’re alienated from their communities and families and they’re alienated from the society at large,” said Dallaire.

“There was a real disconnect from mind, body, spirit and emotion, which are the four grounding components of Indigenous life. Their spirit had been damaged, their physicality had been damaged, their emotional had been damaged and their intellectual had been damaged, so they were very, very wounded, looking at life through a traumatic lens.”

Most Indigenous children within non-Indigenous foster families do not thrive as they have been detached from their culture, said Sinclair.

“They come out of it not knowing where they come from, where they’re going, why they’re here and who they are,” said Sinclair.

He added that social workers need to realize that Indigenous children are harmed by the child welfare system they work for.