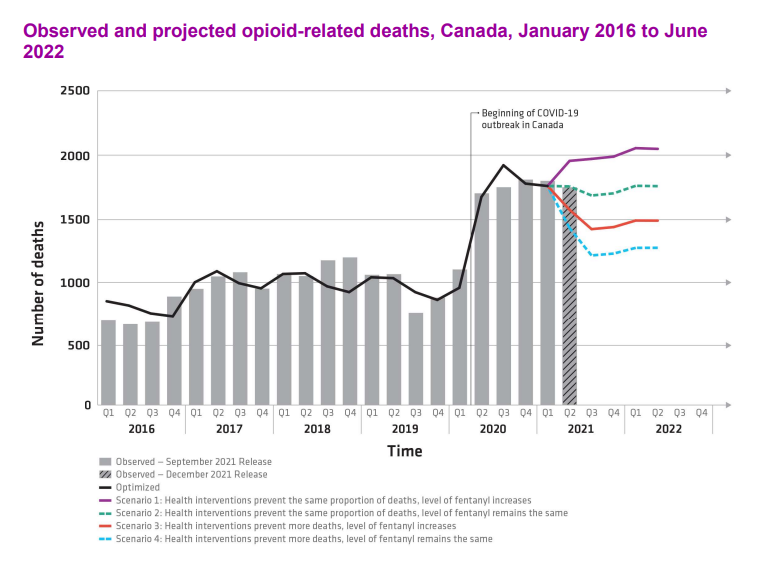

A projection from the Public Health Agency of Canada that opioid-related deaths could remain high and possibly increase into the summer of 2022 has local experts pushing for better treatment and harm reduction in the Toronto area.

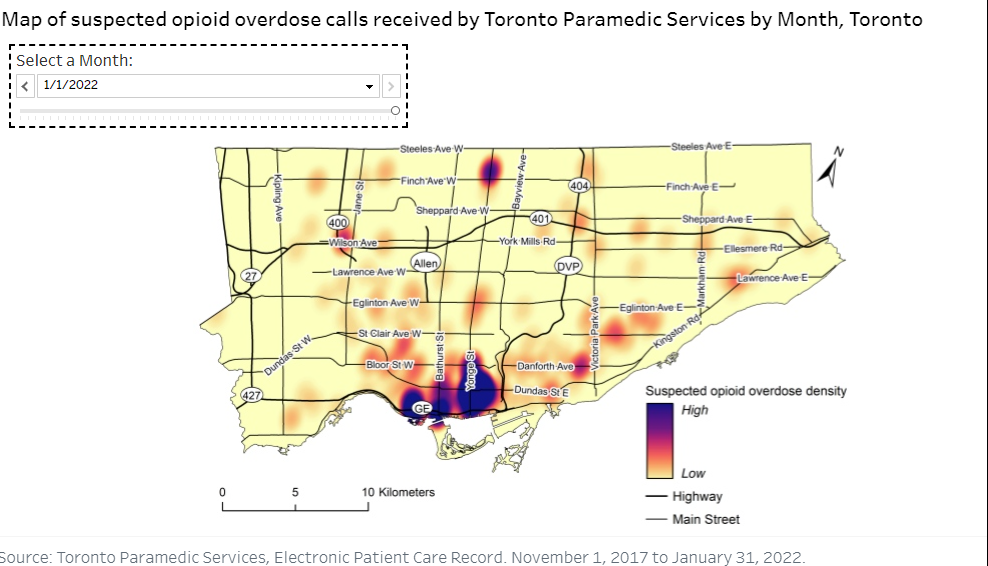

Last year, the Toronto Paramedic Services (TPaS) received over 1,100 calls to the Church-Yonge neighbourhood for suspected opioid overdoses, the highest concentration of calls in the Toronto area.

A statement released in December 2021 by co-chairs Dr. Theresa Tam and Dr. Jennifer Russell said new modelling suggests in the next six months opioid-related deaths could remain high and even increase through the summer of 2022. Projections show that between 1,200 and 2,000 individuals could lose their lives by June 2022.

In the statement, Tam and Russell said, “While harm reduction interventions are essential, we must not lose sight of the importance of the broader conditions that impact substance use.”

They pointed to the broader context in which substance use takes place, saying that one important effort to prevent substance use-related harms is to reduce stigma and discrimination.

Corinne Hart, a harm reduction expert at Ryerson University and former public health worker, says it’s important to remember we can’t label drug use as one issue, as it is a symptom of larger problems.

“We recognize that there are all sorts of reasons both individual, structural, social and environmental, that people will engage (in drug use). It’s a coping strategy or it’s a response to other kinds of things,” said Hart.

Angie Hamilton, executive director and co-founder of Families for Addiction Recovery, believes that the stigma around substance use needs to change.

“One of the biggest problems is you have a choice whether you do this or not, once you do it, you’re a bad person, you’re a criminal… And that is a huge part of the problem. It adds to the stigma, it prevents people from getting help,” Hamilton said.

Both Hamilton and Hart also believe this issue stems from the lack of resources available during the pandemic, isolation and poisoned drug supply.

In November 2021, a report for action was brought to Toronto city council concerning a poisoned drug supply crisis in Toronto. It called for a safer supply of substances, decriminalization of drugs for personal use in small amounts and for expanding harm reduction, prevention and treatment services.

Hamilton states that criminalizing drug use is not working and that we have to change the culture around the outlook on drug use. She says there is a difference between criminal laws and health laws.

“It’s not gonna help somebody to arrest them for trying to kill themselves…It’s the same thing with substance use disorder, which to me, is what we’re really trying to prevent,” said Hamilton.

This action was supported by the Toronto city council, though Hamilton believes this is an issue that needs national attention and should be addressed by the federal government.

Criminal laws are meant to protect us from other people, health laws are there to protect us from ourselves.

Angie Hamilton

“The fact that they’re being asked to do this is outrageous, because this is a federal jurisdiction matter… They’re saying, we’ll entertain requests from individual cities,” said Hamilton. “Well there’s 5,000 municipalities in Canada, we’re going to do this 5,000 times.”

The pandemic has also impacted many of the support programs that Canadians rely upon to get help for their disorders.

In a report released by the Canadian Centre on Substance Use and Addiction (CCSA) about the impacts of COVID-19 on drug users, they highlight that due to the pandemic, many addiction support services were unavailable or were moved online. They state that these online sessions can sometimes have up to 200 individuals, which makes it difficult to provide personal care. One respondent in the report even stated that half of their in-person cohort had been separated due to the pandemic.

The CCSA concluded with the fact that there are no substitutions for in-person meetings as these in-person sessions, “…build connection and trust and bring accountability to the relationship.”

Though when it comes to harm reduction programs, Hart says that many of them aren’t aimed at everyday people.

“The other thing that’s so important with harm reduction is there is so much drug use that happens in private by people who are not technically in that demographic of homeless,” said Hart.

Hart says she can recall two or three previous students who had family members that couldn’t access drugs from a safe source and overdosed. She described them as middle-class people who had chronic pain.

“When we think about harm reduction, we think of homelessness. But the drug problem is so much bigger and embedded into so many other things,” said Hart.

Hamilton, who played a part in the Toronto city council action, experienced substance use disorders within her own family and started working in addiction recovery to provide others with help and support based on her lived experience.

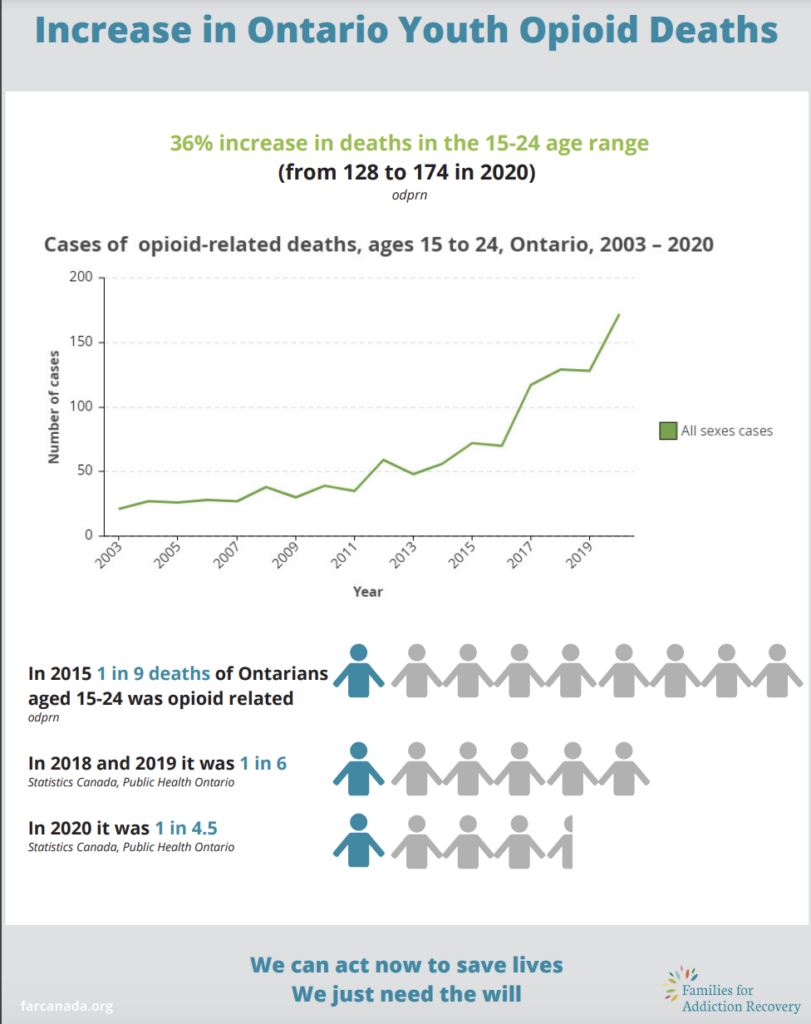

Ontario has also seen a rise in the overdoses of those aged 15-24, according to numbers given to On The Record by Families for Addiction Recovery. In 2020 one in every 4.5 deaths in those aged 15-24 were opioid-related, compared to one in six in 2018 and 2019.

“Ninety per cent of the time substance use disorder develops during someone’s adolescence. The ones that are most affected by substance use disorder are young adults so this is something that adversely and disproportionately affects young people,” Hamilton said.

Hamilton further stated that substance abuse disorder is a pediatric illness and those who start using before the age of 15 are six times more likely to develop a substance abuse disorder by the age of 21.

“When your child is self-harming, you’re afraid. And how do people react when they’re afraid? Well, they yell and scream, they threaten, all kinds of stupid stuff. It’s like getting mad at somebody for not being well, it’s not going to work. I understand the fear. And I can validate that fear… everybody needs to work on recovery, the families have a parallel journey of recovery.”