Toronto residents will cast their votes Monday in this year’s municipal election, and Ward 13 is in a prime position for change since former incumbent Kristyn Wong-Tam transitioned to provincial politics. Eight candidates are on the ballot for Ward 13/Toronto Centre. Ward 13 is bordered by Bay Street, College Street, Yonge Street, and Dundas Street to the west, The Esplanade to the south, the Don River to the east, and Rosedale Valley Road, Mount Pleasant Road, Bloor Street, and Charles Street to the north. Though it is the smallest ward at under six square kilometres, it has one of the highest population densities in the city.

Transit:

Each of the candidates interviewed mentioned that investing in transit will improve the city’s carbon footprint. They support the electric transition of the TTC’s bus fleet, as well as more charging stations for electric cars.

Candidate Caroline Murphy supports the construction of the proposed Ontario Line, but says she is worried about timelines being met.

Murphy has worked as a senior staffer and independent consultant for many years in the financial services sector. She is the president of the Cabbagetown Resident’s Association, and has also owned and operated a small restaurant and pub. Her approach to politics is a holistic one, and believes all of the city’s issues are intersectional.

“I’m not seeing that the planning is properly in place for what we’re about to go through with the Metrolinx line that’s going to come through Ward 13. So the first thing that we have to do is hold to account the city partners as well as Metrolinx. We have to ensure that there is an actual plan in place, and be able to hold to account timelines, community engagement, make sure that we are compensating the local businesses and working with the residents.”

Meanwhile candidate Colin Johnson is pushing for changes in the arterial designations of certain streets. He says this can help alleviate traffic caused by people driving into the city from the Don Valley Parkway.

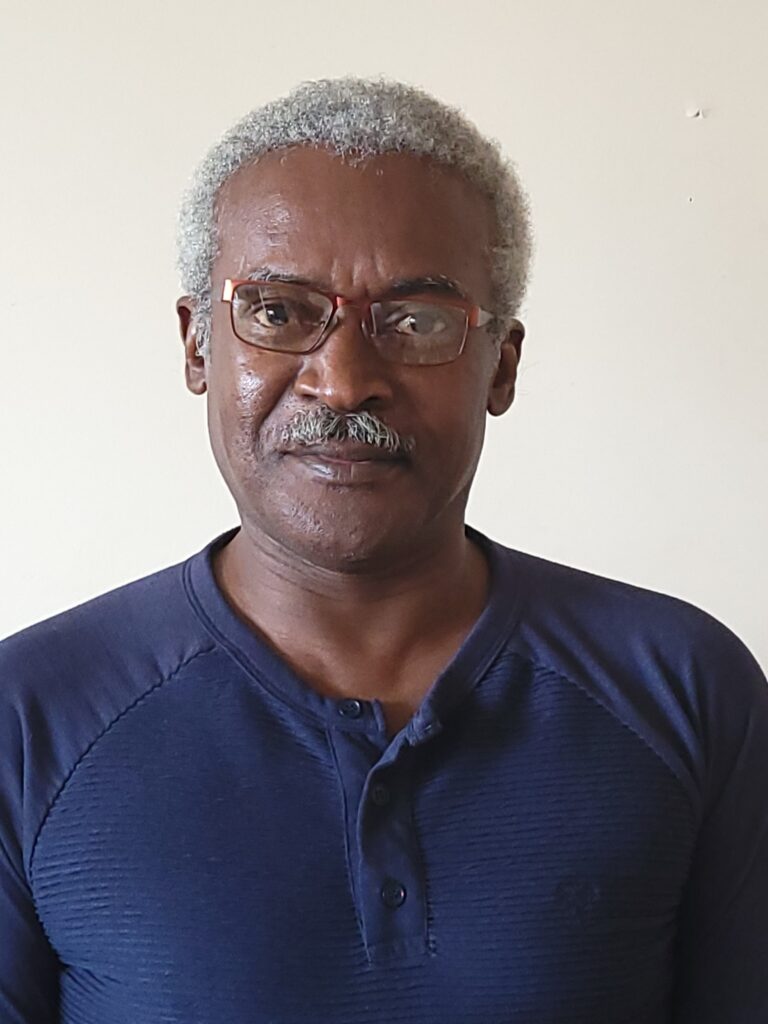

Johnson has worked as a consultant for all levels of government, non-profits, and universities on HIV, human and women’s rights, LGBTQ2S+ rights, anti-racism, harm reduction, decriminalization of substances, the overdose crisis, and decolonization. He helped to create GAY (Gay alliance at York) Toronto in 1975, is the chair of THRA (Toronto Harm Reduction Alliance), and the vice chair on the PASAN (Prisoners AIDS Support Network) board.

“We need to have a more coordinated transportation model. I believe that since Sherbourne does not have a lot of businesses on it, it can be re-designated as a major arterial road.”

As for the proposed Ontario Line, Johnson wants to see an additional station added at Gerrard and Parliament Streets.

“It needs to have a stop somewhere in Regent Park. That would alleviate a lot of traffic and the Parliament bus would then have two stops that it can make.”

Candidate Miguel Avila and member of the Municipal Socialist Alliance, says “We’re spending a lot of money on enforcement, and instead of going that route I think that subsidies can go to regular Toronto residents who are unable to afford the full fare.”

Avila is an Indigenous activist, resident of Regent Park, and member of the Regent Park Neighbourhood Association and the Coalition for Community Benefits. He is passionate about social and environmental justice, housing, police accountability, and food security.

He also expressed concern at the lack of availability of wheel transit for people who have disabilities.

As for construction of the Ontario Line, Avila sees opportunity in the likelihood that the project will take ten years to complete.

“I want to see job creation for residents. They can be hired on the project to alleviate some of the other problems that we have, like lack of employment.”

Citing the failure in delivering the Eglinton LRT on time, Avila is concerned about Metrolinx, which is owned by the province. To hold them accountable, he suggests calling on the ombudsman to investigate where things went wrong.

“Metrolinx needs to be aware that the public is always watching and learning, and they have to be serious about the delivery of these projects.”

Public Safety:

All three candidates agree that mental health and drug related emergencies should not fall to police, but to unarmed crisis response teams. They all wish for existing pilot projects to be finalized and implemented citywide.

Johnson said he is concerned that at $1.23 billion per year the police budget is too high, and that too many of those funds go towards salaries. He also says that the police should not be paid overtime, and that the requirements should be more strict. “I believe that to become a police officer you should at least have a degree in something relevant. So something along the lines of psychology, sociology, police studies, or criminology.”

Johnson also would like to see traffic-calming responsibilities shifted away from police.

“I’d like to instead see traffic wardens created… So instead of a cop standing at a construction site, you’d have a traffic warden.”

Murphy “firmly” supports more community policing.

“I’ve talked with people in St. Jamestown and Regent Park and they’re crying out for more community neighbourhood liaison style policing. Because when that’s in place, and the police officers are working with the community, to the nuances of the community, that’s when people start to develop trust and feel safer.”

Even so, Murphy says she understands why there is criticism of the police.

“Part of moving forward is us [holding them to] account, and helping to create an environment of navigating the union so that bad apples can be removed.”

Murphy also mentioned the creation of “safety zones” with direct phone lines to connect people in crisis to emergency services. These would connect users to an operator who would determine the appropriate response.

Citing deep mistrust in the police from certain communities due to profiling, mismanagement of cases involving minorities, and police brutality, Avila says he believes that more needs to be done before the city considers increasing community policing.

“The problem starts with training. We first need to equip our officers with the skills necessary to meet the needs of all communities. Don’t put the horse ahead of the cart. Get your house in order first.”

Avila supports the idea of requiring police to obtain a relevant degree, defunding the police by 50 per cent, and diverting those funds into other public safety resources, like crisis response teams and mental health support. He believes that we need to start being more innovative in our approach to community safety and come up with ways for the general public to participate.

He gives an example from Winnipeg where “the Indigenous community patrol the streets. They have something called the Bear Clan patrol. The idea is that neighbours, people from the community walk the streets and watch the community for anything that is not welcoming. They have been able to reduce the level of violence, especially against women.”

Housing:

Murphy, Johnson, and Avila agree that one of the best ways to improve the housing crisis is to reform the Toronto Community Housing Corporation (TCHC).

“I don’t believe in tearing them down for the sake of it and just going ‘you know what, you did a crap job’. It is about what is salvageable. What is sustainable? And what can we build and improve upon?” Says Murphy.

She suggests the housing problem is two-pronged: getting people into homes, and keeping people in homes.

“If we just keep increasing the cost of living and increasing taxes and so forth, then [residents] are going to be struggling to maintain homeownership and maintaining the structure of the home in a livable, decent way.”

She acknowledges the growing population in Toronto and the lack of low-cost dwellings. She believes that surcharges should be levied against developers who fail to make at least 30 per cent of their units affordable.

“Not affordable with all sorts of loopholes and catches, but truly affordable to what the community that they’re building in needs.”

This involves investing in social development plans. Although Murphy acknowledges the shortcomings of phase four of the Regent Park development plan, she believes in the value of the project, and that improving upon past mistakes instead of discrediting social development plans will make communities like Moss Park more successful.

Avila believes TCHC reform starts with making changes to its board.

“When it comes to representation, there are only three residents on the board, and the rest are appointed by the mayor, or they’re councillors, or they’re people with expertise. If we increase the number of residents on the board, then we’ll see a positive change that will put our priorities first.”

With regards to future social development projects, Avila said we need to prioritize community consultation.

“When I came to live in Regent Park the ratio of 30 per cent affordable housing and 70 per cent new condominiums was already in place. But if I was part of that conversation, if I was consulted, I would go for 50 per cent.”

Avila also has a message for current and future residents of social development projects such as Moss Park: “Get organized. Tenants in those communities need to have their own neighbourhood association.”

Aside from changes made to the board, Johnson offered operational solutions for the TCHC.

“The Toronto Community Housing Corporation needs to get it together, sell off some of the properties they have, make partnerships with other organizations, be they HIV organizations to house people living with HIV, LGBTIQ organizations, groups for battered women, transitional housing for people who are trying to quit substance abuse.”

Johnson also supports the licensing of rooming houses.

“A lot of people cannot afford to rent nor do they want a cool apartment, they just want a little room. We also need to allow for triplex and co-op developments. Co-ops work.”

Johnson sees the Regent Park development as a failure, and wants to ensure that future social housing developments are built to attract high and low income residents, with enough units and services to accommodate demand.

“They don’t have a library, and they don’t have a school. People aren’t going to move into an area unless they have [adequate support].”

When it comes to homelessness, Johnson, who has experienced homelessness himself, suggests that some homeless people do not desire a home but that for those who do, we need an immediate temporary solution.

“You can either rent space, which they have done in the past, or there are other buildings that exist that are not purposely being used. We can put them in there.”

“We need to realize that [some] prefer to be on the streets. That is where they make their money, that is where they contact their friends, and that is where they have their services.”

The remaining five candidates OTR reached out to either declined to comment or did not have contact information easily available.

Editor, On The Record, Fall 2022.