The earth two billion years ago was an inhospitable place. Days were only 15 hours long, no complex life had yet formed, and humans couldn’t have sustained life, as the atmosphere contained too little oxygen to breathe. There was no greenery yet on our marble of a planet, but somewhere in what would eventually become Ontario sat some rather large rocks. Though they may have been unremarkable at the time, these choice hunks of pre-Cambrian stone witnessed the earth’s coming of age and would eventually reside at the centre of Ryerson University. You may think Kerr Hall or your tenured history prof are old, but rest assured, the rocks at Lake Devo are much, much older.

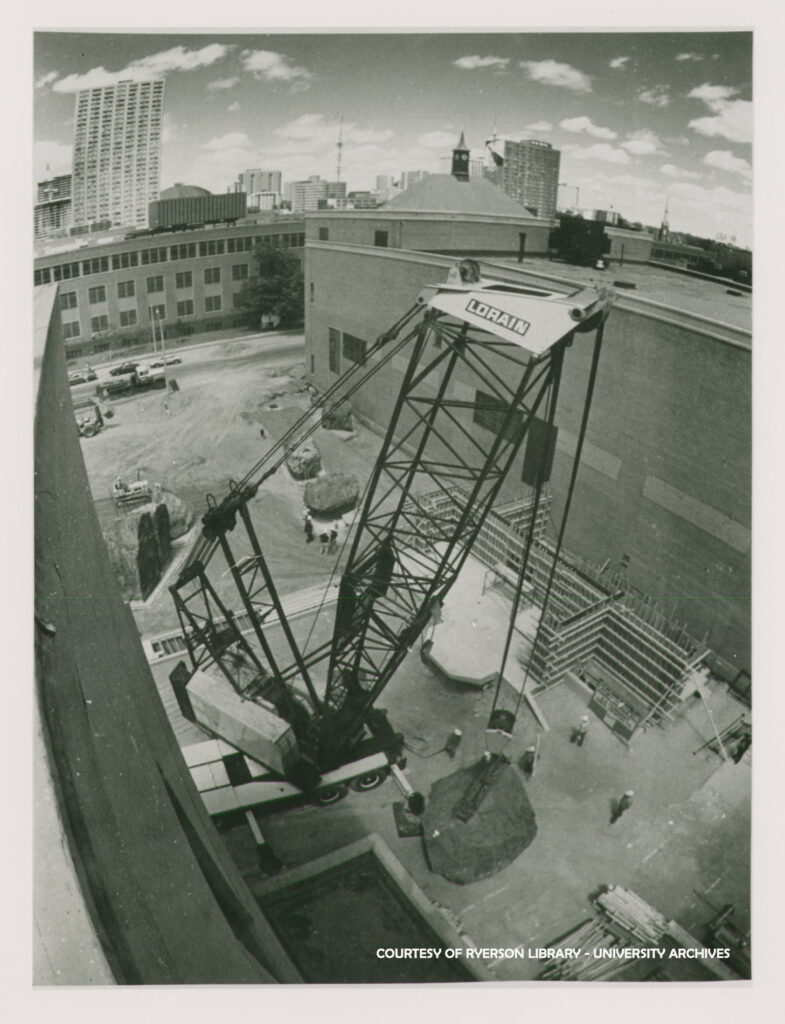

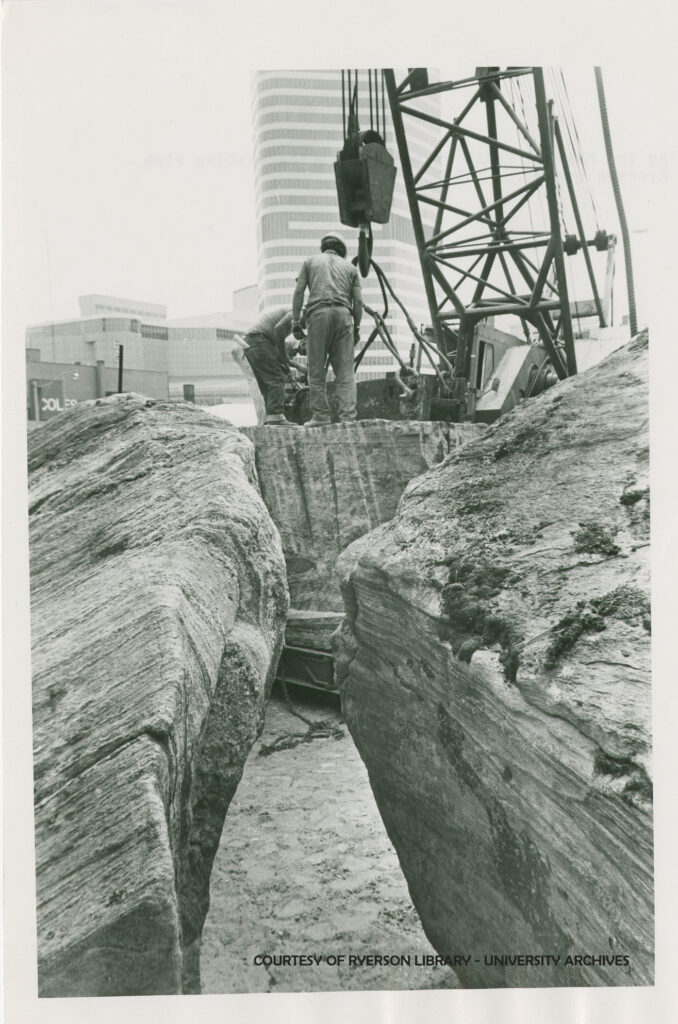

According to Ryerson’s Facilities Management and Development department, the rocks led a stoic life embedded in Muskoka’s Canadian Shield until one Richard Strong came along. Commissioned to design what was then known as Ryerson Community Park in 1977, Strong went to Muskoka and personally selected the boulders, according to previous reporting by Larissa Liepins for the Ryersonian, as On The Record was then known. The rocks cost $277,000 at the time, which, when adjusted for inflation, amounts to over $1.1 million today.

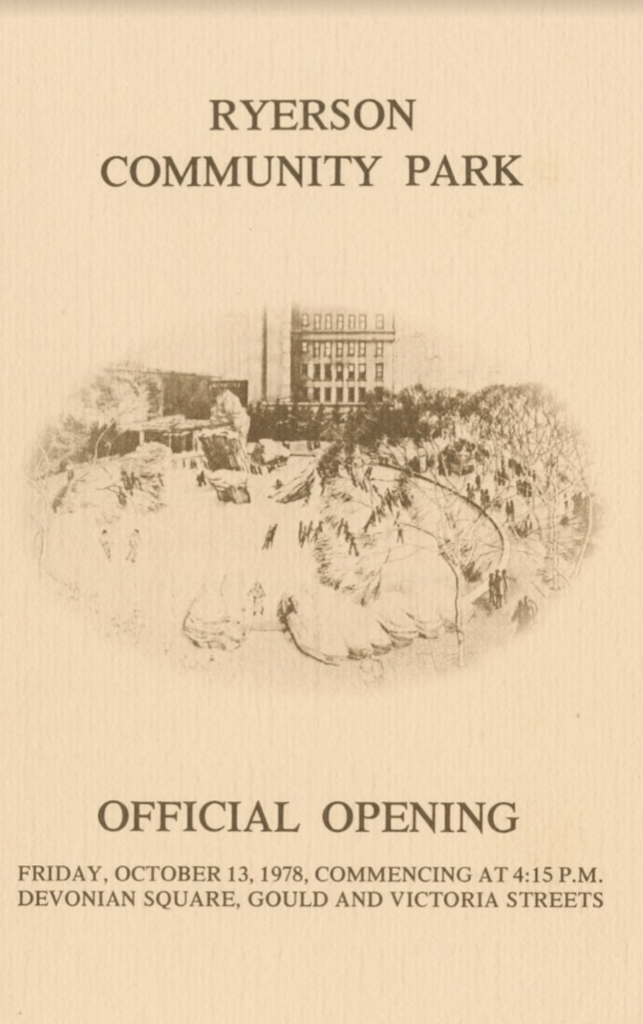

The lake and accompanying park opened to great fanfare under an overcast sky on a crisp mid-October day in 1978. The university’s then-president and future namesake of Pitman Hall, Walter Pitman, started the event off with a speech, and two Toronto mayors (one former and one acting) were among those gathered to see Ryerson’s newest installation. Guests were then led on a walking tour.

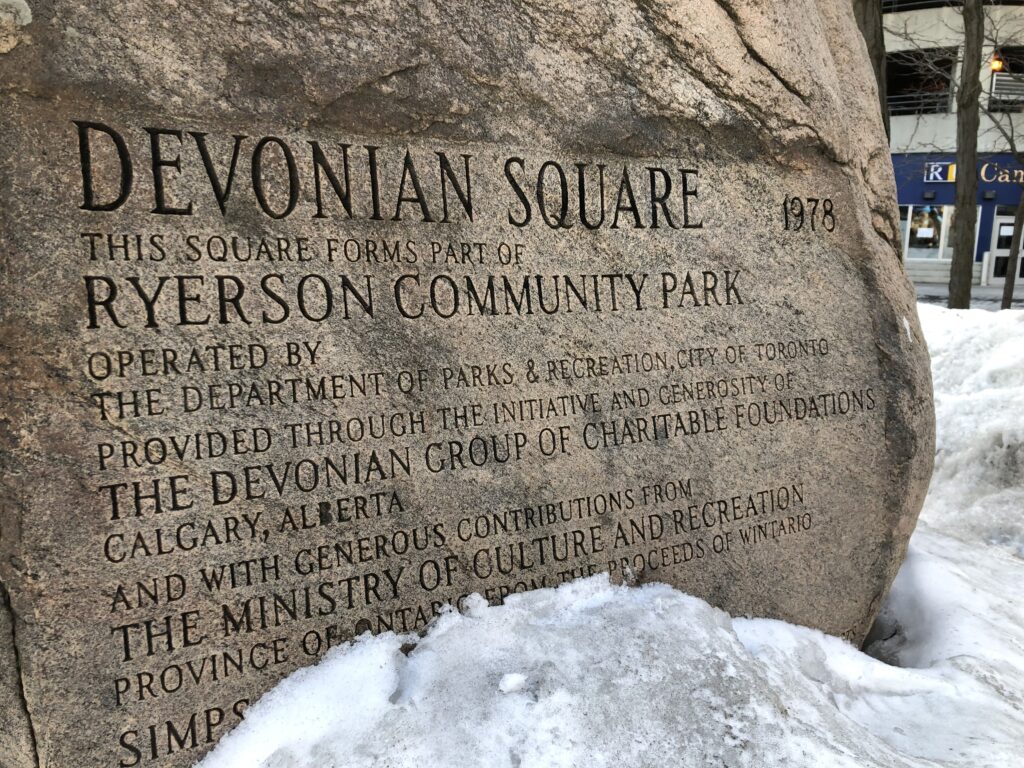

Of course, the rocks didn’t just appear on Ryerson’s campus by themselves. Their arrival was largely made possible by the Devonian Group of Charitable Foundations, which was started by Eric Harvie in the ‘60s. A hero of the First World War and Ontario native, Harvie made his fortune in the oil business, leasing black gold-laced land to Imperial Oil. On one attempt, drillers struck a Devonian reef (a geologic period that modern oil can be traced to), and Harvie instantly gained millionaire status. He also found the name for his future philanthropic foundation, whose root accounts for the ‘Devo’ in ‘Lake Devo.’ Other donors who made the installation of the rocks possible included Wintario, Simpsons-Sears and the City of Toronto.

However, the park that the Devonian Group and others sponsored in 1978 is a far cry from what sits at Lake Devo today. Much of the landscape was lopped off to make way for the AMC Metropolis movie complex, a decision that didn’t sit well with Harvie’s family.

Harvie had died by the time the decision was made to shrink the park, but his daughter, Mary Ann Cormack, told Liepins that she was “extremely upset that the university couldn’t honour an agreement that was signed.”

The area around Lake Devo was further encroached upon when four of the stones met an untimely end in 2004 to make room for construction of Heaslip House. The once boulders were reduced to rubble and dumped at the Leslie Street Spit.

Lake Devo and its rocks have remained relatively the same since then; passive observers of campus life for countless Rams during their time at Ryerson. The lake’s flat concrete bed becomes a de facto skatepark in the summer, and attracts a different type of skater when frozen over in the winter. “It’s the skating rink with the rocks,” Daena Galam, a Ryerson student, said. “It wouldn’t be the same without them.”

Paul O’Neill agrees. An elevator repairman who was on campus working for Schindler, O’Neill said he enjoys skating at Lake Devo in the wintertime. “The rocks add some atmosphere,” O’Neill said. “It’s better than having it be just wide open space.”

Lake Devo’s rocks have stood strong through all of the changes on campus, and offer a concept of permanence at an ever-evolving university. They’ve become an iconic (albeit out of place) symbol of Ryerson, so next time you pass by, don’t take them for granite.

Trevor Popoff was the features editor at On The Record in the Winter 2022 semester.