Listen to the whole story here:

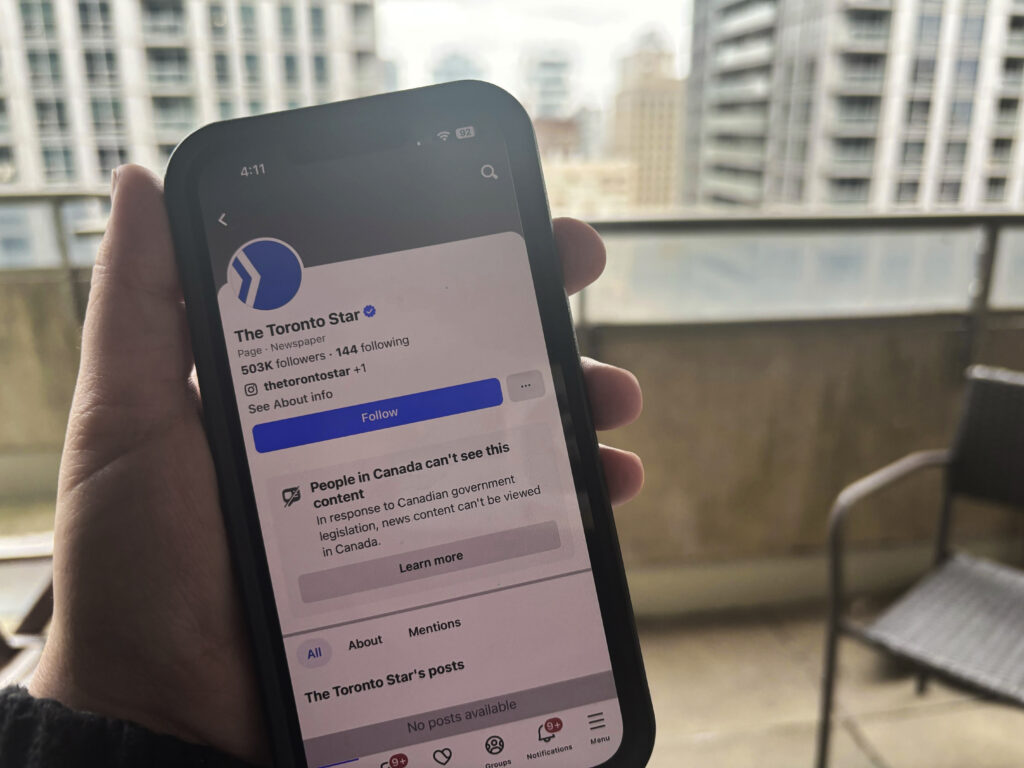

This federal election will be the first since Meta’s news ban took effect in Canada, a policy many have denounced for the harm it’s caused small local news outlets across the country.

In June 2023, the Canadian government passed Bill C-18, also known as the Online News Act, requiring companies like Google and Meta to negotiate with and compensate Canadian news organizations for the content news outlets share on media platforms.

While Google came to a separate agreement with the Canadian government, news started to disappear from Meta’s platforms (Facebook and Instagram) for users in Canada on Aug. 1, 2023.

Without local angles, political stories may become less compelling to people, which could result in people becoming less engaged in federal politics, said Bill Curry, The Globe and Mail’s deputy bureau chief in Ottawa.

“We’re losing those local stories that are still about federal politics but have more of a local angle,” said Curry.

People have lost the habit of watching the 6 o’clock news or reading the paper every day, so they are getting their news in bits and pieces, he said.

Between 2008 and Feb. 1, 2025, 529 local news outlets closed in 351 communities across Canada, according to the Local News Map, a joint initiative of the Local News Research Project at Toronto Metropolitan University’s School of Journalism and the University of British Columbia’s SPICE Lab (spatial information for community mapping).

“I think there is a growing percentage of Canadians who are completely disconnected from the news,” said Curry.

Less news is being consumed by Canadians, according to data collected by the Media Ecosystem Observatory and released on Aug. 1, 2024, with an estimated reduction of 11 million views per day across Instagram and Facebook due to the ban.

“The Meta ban has cut off one more access point for people to political news,” said April Lindgren, co-director of the Local News Project and professor emeritus at TMU’s School of Journalism.

“The risk is that people will pay even less attention and be less informed about political decisions that could have a big effect on their lives,” said Lindgren.

The Media Ecosystem Observatory data indicates three-quarters of the Canadian public aren’t even aware of the ban, with only 22 per cent of Canadians aware that news is banned on Facebook and Instagram.

What’s real and what’s fake?

The effect of the Meta ban is huge, said Barry Acton, a freelance media producer who has covered multiple federal election campaigns, most recently in 2008.

“It’s harmful because news outlets can’t put something on Facebook, but third-party players can, so the lack of balance and fact-checking is huge,” said Acton.

According to Statistics Canada’s Survey Series on People and their Communities, 44 per cent said they typically got their news or information in 2023 from social media accounts unaffiliated with government, scientific or news organizations.

Misinformation is a massive issue that is going to require an all-of-industry response, said Raisa Patel, a national politics reporter for the Toronto Star.

“You can pump out accurate information, but because we’re in a culture of misinformation, people are going to believe you’re reporting misinformation, which also creates a lack of trust in the media industry,” said Patel.

“The resources that the industry used to have just simply aren’t there anymore, especially for smaller outlets,” she said.

In 2023, 43 per cent of Canadians polled said they thought it was becoming harder to distinguish between true and false news or information compared with three years prior, according to Statistics Canada data.

“This puts a requirement on the audience to actually be their own editor, and to do a little bit of research and determine whether that source is reliable,” said Chris Waddell, former director of Carleton University’s journalism school.

Another barrier to the spread of political information during the upcoming federal election is the deliberate strategy of politicians to absent themselves from political debates and refuse interviews, said Lindgren.

“I think the deliberate strategy of avoiding media is a blight on the democratic process,” she said.

Cutbacks at major broadcasters and the closing of radio stations all add up to less scrutiny on the local side of what federal members of parliament are up to, said Lindgren.

“We’re getting squeezed by two sides, by the economics of the industry — fewer jobs, do more — and then by the politics of the world,” said Acton.

Reporting from the campaign, without Meta

Paul Berton, editor-in-chief for The Hamilton Spectator, said the paper plans to keep its coverage local this coming federal election for economic reasons and to align with the interests of their readership.

“Our readers are most interested in how federal politics affects their communities,” said Berton.

Some federal election reporters don’t plan on making any major changes to their reporting, while others say it is important for journalists to become more creative.

Since the Meta ban has been around for a while, Curry says his newsroom is not expecting any major changes to how reporters work.

“We’ll continue to aim for a mix of immediate reporting on the day’s events and more in-depth pieces that take more time,” he said.

Meanwhile, Patel says journalists should become more creative with their approach to reporting.

Travelling to notable places and finding stories you can cover from afar are some creative approaches to reporting on elections, she said.

“This is a good opportunity for news organizations to switch their approach,” said Waddell.

“Seems to me a good opportunity for news organizations to spend less time covering leaders and more time out there across the country, listening to what voters are saying,” he said.