After a year of remote learning, Ryerson film students continue to struggle with limited hands-on opportunities

With hours of pandemic safety preparation behind her, Gloria Burke was ready to shoot Yellow Tangerines, the thesis film she’d been looking forward to since starting at Ryerson University’s film studies program nearly four years ago. She had the five-page COVID-19 safety plan she’d written in hand — it outlined plans for daily temperature checks, quarantining gear and individually wrapped meals. Burke’s team had raised $2,300, purchased personal protective equipment, and completed an online COVID-19 safety course.

But in mid-January, about two weeks before the film’s scheduled start date, everything came to a halt when Ontario went into lockdown again. The School of Image Arts informed students they could have only five people on set at a time. That was just impossible for Yellow Tangerines with its six-person cast and 15-person crew. Burke and her team postponed their shoot until late March, hoping the COVID-19 situation would improve.

Delayed shoots, disjointed collaboration and limited access to equipment are just some of the issues Ryerson film students are facing during the pandemic. Many feel concerned about the opportunities they’re missing, frustrated with the limitations of online learning and disappointed by the year they’ve spent isolated from campus and their peers.

“The notion of it being online was really disheartening,” says Burke. “I’ve worked my ass off for the last three years just to have it be dwindled down to this experience.”

The Yellow Tangerines Kickstarter page says the short film aims to “capture what it is like to be in your 20s right now.” The film follows a young woman who, after a fluke encounter caused by a runaway peach, spends the day with three older women at their bakery. Eventually, she’s able to open up about her struggles and let others in.

As the producer, Burke is responsible for co-ordinating all of the COVID-19 safety measures for Yellow Tangerines. With three actors in their 60s or 70s on set, they can’t take any chances. “Half of our work was going into COVID protocol,” she says. “You’re liable for everyone’s health to a much greater degree.”

COVID-19 has not only affected Burke’s thesis, but her graduation too. She has deferred until December 2021 in hopes of finishing her degree on the campus she holds dear to her heart. The Ryerson Image Centre, she says, is its own kind of community. The array of brightly coloured lights that line the top of the building, illuminating the corner of Gould and Bond Streets, act as a beacon for the rest of campus at night. In better times, visitors on the daily 2:30 p.m. drop-in tours roam around the galleries and exhibitions. Elsewhere in the building, editing suites and production studios bustle with the sheer energy of collaboration. This is where crews are made. Directors find producers, cinematographers find screenwriters, and editors find sound mixers.

Now, the Image Centre is closed, except for pre-arranged appointments. There is limited access to production spaces and professional-grade equipment. Neon “Up Only” and “Down Only” arrows line the staircases. The only unmasked faces are the ones printed on a large yellow sign at the entrance, depicting a fever, a runny nose, and other symptoms that visitors cannot have.

To have that space taken away? “Heartbreaking,” says Burke.

Nakita Johnson chose the film studies program at Ryerson because of its focus on hands-on learning and the resources available to students. “I’m in my second year, and I can’t use any of that. It kind of makes me feel like I made a mistake,” she says of her pandemic experience.

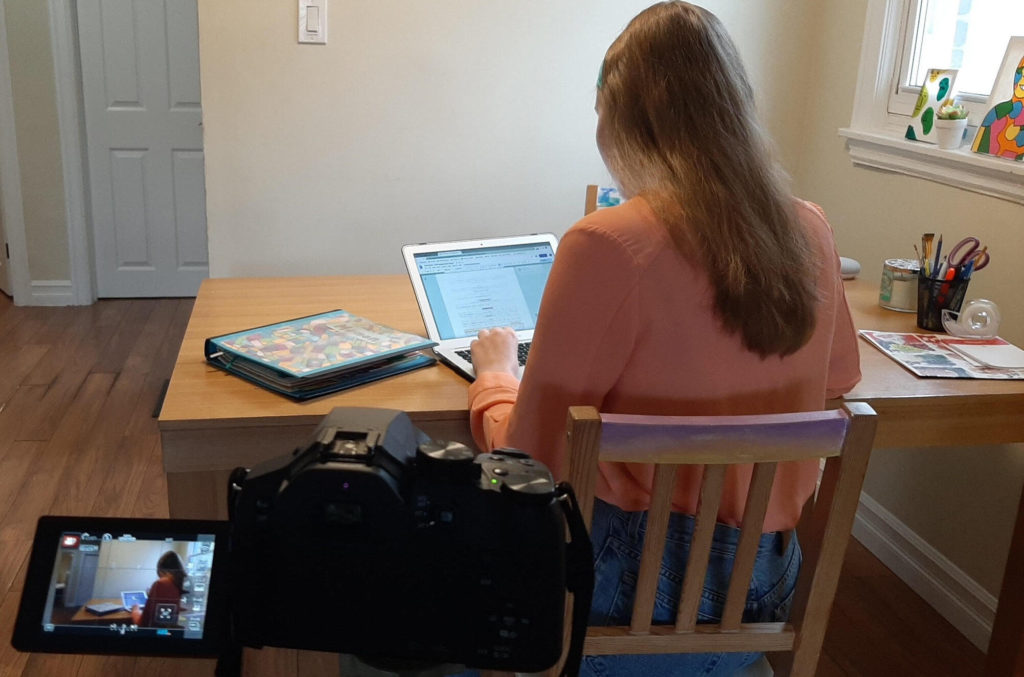

Now, instead of hands-on classes, some professors pre-record videos demonstrating how to use equipment that most students don’t have immediate access to. The only equipment film studies student Fatemeh Saba Forouzan has besides her cellphone is her mirrorless camera. “Even then, I’m one of the lucky students,” she says.

Forouzan and other film students would normally have access to a foley room at Ryerson. The soundproof room is equipped with materials needed to create everyday sound effects, like wooden planks that mimic the click of high heels. Now, if Forouzan needs to record audio, she pulls the duvet off her bed, goes into her closet, and places the duvet over her head. The technique eliminates some echoes, but the sound quality still doesn’t compare.

She also struggles to complete assignments on a four-year-old computer that can’t run editing software. “I have projects now that I have to do on After Effects with a computer that refuses to run After Effects. That’s an impossible scenario,” she says.

This frustration expressed by Johnson and Forouzan is about more than just inconvenience. “I feel like this was a year wasted,” Johnson says.

“I feel like I didn’t learn anything at all this past year,” echoes Forouzan. “I feel like I didn’t get anything out of my education.”

The themes of isolation in Yellow Tangerines reflect the experiences of not only Burke and her team, but many film students struggling with a lack of social interaction. The film studies program thrives on collaboration. “In film especially, the people that you’re with make your experience,” says Burke. She says that virtual classes have made networking more challenging, while others have encountered issues with group work.

“It still works, but it’s not enjoyable at all,” says Johnson. She opted out of in-person filming for her group projects, not wanting to put herself or her roommates at risk. But she laments the opportunities and connections she knows she’s missing out on. “I’m at my prime. I should be meeting so many people. I should be making all these contacts. And I feel lonelier than I ever have,” she says.

Others are finding creative ways around the restrictions. Forouzan enjoyed working on a self-portrait film in the fall semester, and another project using existing footage of American presidents.

Burke shot Yellow Tangerines in late March as Ontario cautiously began to reopen. Before the shoot, she said she was sad that filming was “going to feel very clinical.” As she anticipated, the atmosphere on set didn’t feel the same — everyone had to keep their distance physically, there was no catering spread to pick at throughout the day, and as the actors’ masks came off, the crew’s face shields went down.

But watching screenings of her classmates’ recent work left Burke feeling optimistic. “The hope has come from everybody else just trucking on and going through this,” she says. “People are still pulling this thing off.”