Listen to the whole story here:

Woodbridge is one of the most flood-vulnerable neighbourhoods in the Greater Toronto Area, and experts say climate change and decades-old development patterns are making the risks harder to manage.

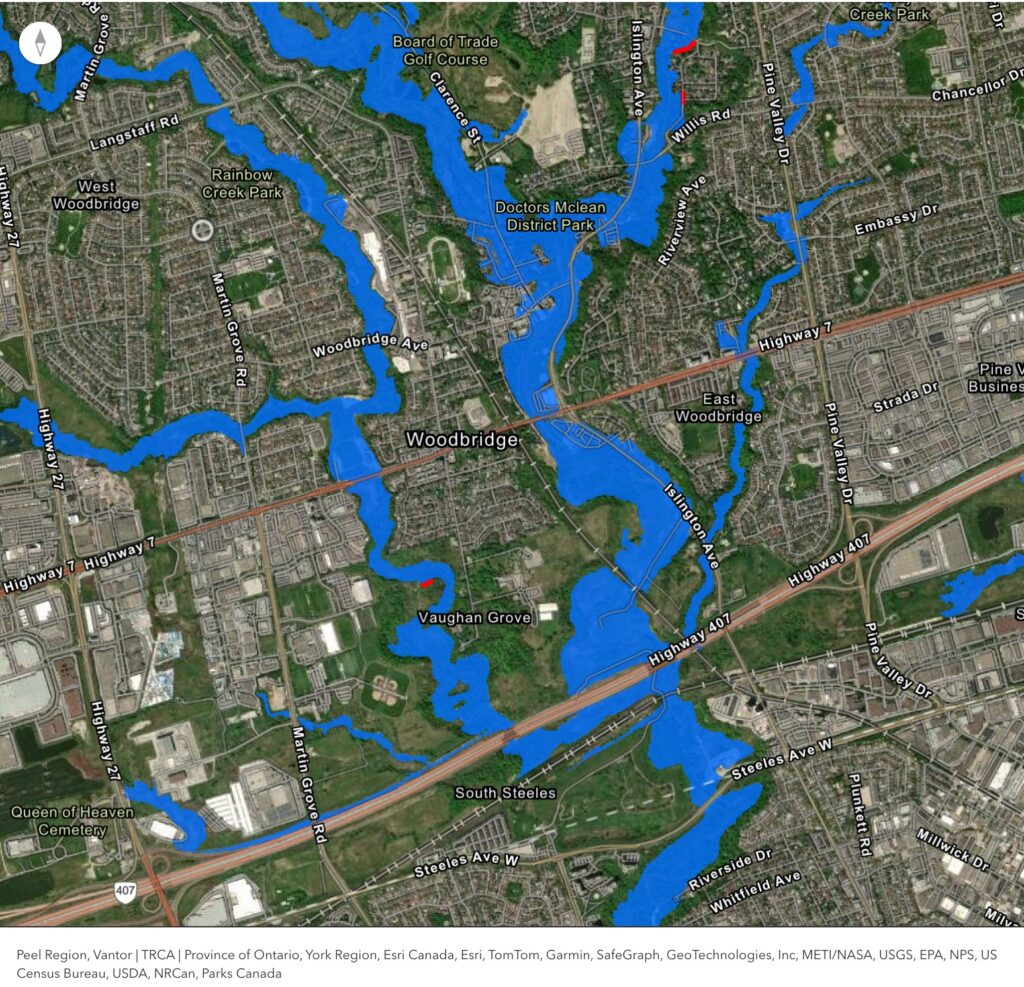

Located along the Humber and East Humber rivers, the area sits in a low-lying floodplain where homes and businesses were built long before modern flood-risk planning existed. The Toronto and Region Conservation Authority (TRCA) ranks Woodbridge sixth among York Region municipalities for riverine flood risk and 20th among 40 high-risk clusters across its jurisdiction.

The neighbourhood’s vulnerability comes down to elevation and history, according to David Kellershohn, associate director of engineering services at the TRCA.

“The dominant factor that contributes to this area being flood-vulnerable is the elevation of the area being closer to the elevation of the Humber River,” he wrote in an email.

Earlier development placed homes directly in the path of future river overflow, Kellershohn said, and urbanization has further increased the amount of runoff entering the system during heavy rain.

Because the community is already built within the floodplain, Woodbridge is designated as a Special Policy Area (SPA) in Vaughan’s Official Plan. The designation restricts redevelopment that could put additional people and property at risk.

TRCA notes that flooding on Woodbridge Avenue could begin during a two-year storm event, meaning there is a 50 per cent chance of that level of rainfall in any year. Major intersections, including Islington Avenue and Clarence Street, are projected to be inundated during larger regional storms.

TRCA studies show Humber River peak flows — and there are now more hard, paved areas like roads, sidewalks, and parking lots — have increased since 2002, contributing to a gradual rise in flood risk.

Environment and Climate Change Canada has also reported increases in average annual precipitation across the country. While residents may feel flooding is becoming more common, the TRCA says rainfall records do not yet show a clear increase in flood frequency, noting that recency bias may be influencing public perception.

Urbanization has a major impact on public perception of flooding, according to Jennifer Drake, associate professor and Canada Research Chair in stormwater and low-impact development at the University of Toronto, because water runs off paved surfaces quickly, overwhelming systems and creating the sense that flooding is getting worse.

“Even before climate change, city building alone increases our flood risk,” she said.

“When rural land becomes roads, roofs and parking lots, we lose huge amounts of the ground’s ability to absorb water.”

Drake says that loss of infiltration leads to more water entering storm drains and rivers at the same time, creating pressure on systems that were not built for modern rainfall levels.

How effective could Vaughan’s tree canopy plan be?

Vaughan is working to expand its tree canopy through its Urban Forest Management Plan, which aims to increase shade, absorb rainwater and reduce urban heat. While trees play a valuable role, Drake says they are not a solution on their own in a river floodplain.

“A tree has a tremendous amount of surface area… the amount of surface area on a tree is easily the same as a building, because it’s so complex with the branches and the limbs. When it rains, that whole tree gets coated in water. That’s called interception,” she said.

Roots also keep the soil porous and allow more water to infiltrate. “When you scale that up to a whole treed area, far more water goes into the ground instead of the sewer,” Drake said.

Still, Drake says, retrofitting climate-resilient stormwater systems into older neighbourhoods is difficult.

“In an already-developed neighbourhood, where do you put these systems?”

Space constraints, high costs and construction disruption all limit what municipalities can implement, Drake says. For immediate impact, she points to simple interventions such as disconnecting roof downspouts from storm sewers.

“Anything is better than sending all that water straight into the storm system at once,” she said.

Kellershohn says no major flood-remediation projects are currently underway in Woodbridge, though work is happening in other parts of Vaughan, though it remains unclear whether Woodbridge’s future upgrades can keep pace with rising flood risk.

Otter AI was used to transcribe audio.