As we come to terms with Egerton Ryerson’s history, let’s consider that changing the university’s name will have symbolic, far-reaching benefits, but also other costs

This story is part of Monumental Challenges, a series looking at Ryerson, reconciliation, and the issues surrounding replacing names and monuments.

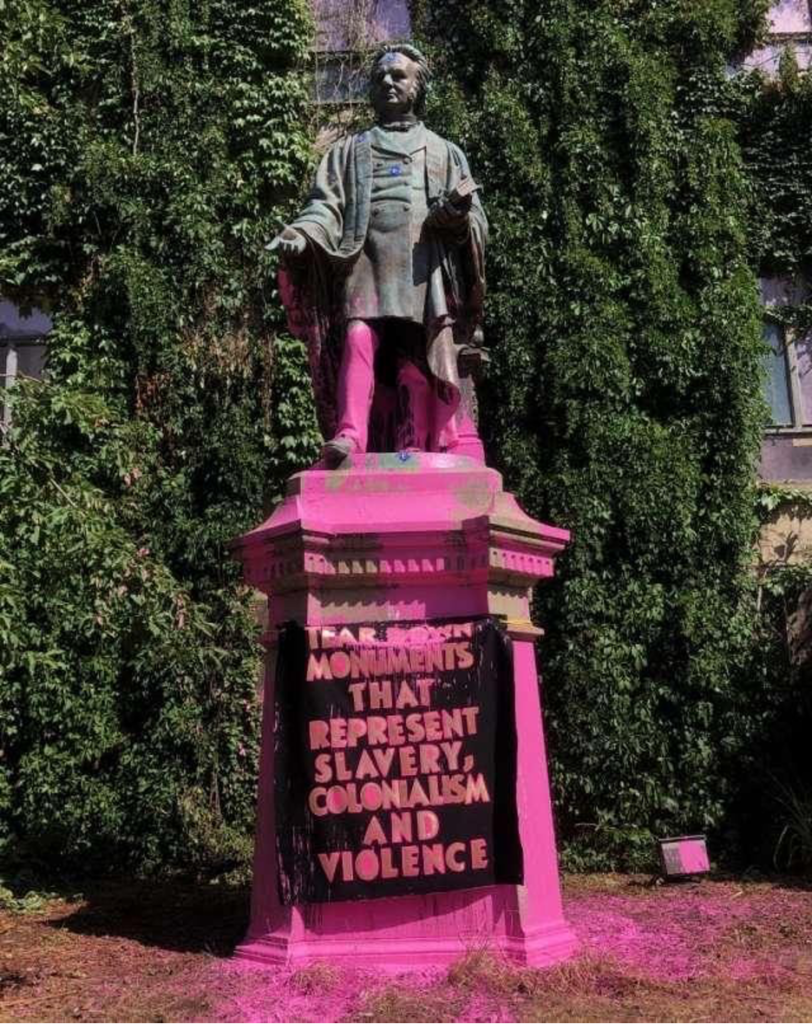

Over the last few months, petitions to take down the statue of Egerton Ryerson have reignited a conversation about whether or not the university should honour Ryerson’s name at all.

Originally called Ryerson Institute of Technology when it opened in 1948, the university has endured pressure to change its name since at least 2015, when a student-led campaign shed light on Egerton Ryerson’s history.

The missionary, preacher and teaching leader advocated for free education. He also had involvement in the creation of the residential school system in Canada in the mid-19th century, which led to intergenerational trauma for Indigenous people in Canada.

Social unrest following the killing of George Floyd has launched a global campaign against monuments, buildings, streets and sports team names that perpetuate racist and colonial ideals. It also has many students at Ryerson questioning, once again, whether or not their university should consider a name change.

And why not? Dishonouring a name that perpetuates social or racial inequities appears like the right and obvious course of action. It also appears to be a simple thing to do – in the world of sports, the Washington Redskins, Edmonton Eskimos, and McGill Redmen dropped their names in what seemed like a blink. But changing an institution’s name is more complex than making a value judgment about Ryerson himself.

When the Washington Redskins changed their name to the “Washington Football Team” in July, the team’s executive vice president Terry Bateman said a temporary placeholder name was necessary because, “a rebrand like this is a 12- to 18-month process.”

Renaming takes a long time because it must be done right. It is a careful exercise in damage mitigation, and while the benefit might be symbolic and far-reaching, the cost is real and can be multi-pronged.

First, changing a name costs money. The most recent Canadian university to alter its name is Western University, which had been the University of Western Ontario until 2012. Simply dropping the “Ontario,” according to Maclean’s magazine, cost $200,000. Victoria University of Wellington, New Zealand, paid $1 million to get rid of “Victoria” in 2018. University of Maryland University College (which, when you read out loud, does beg for a name change) dropped $1 million to become University of Maryland Global Campus last year.

Toronto on Saturday, July 18, 2020. Credit: Ernest Doroszuk)

Second, losing an old name risks alienating students, supporters and alumni. An unmediated decision could place Ryerson in the same boat as Augusta University in Georgia. In 2012, the school changed its name to Georgia Regents University, only to revert back to its original name three years later when student protests erupted on campus, locals voiced displeasure, and alumni stopped donating. Changing the name, and then changing it back, cost the university $8 million in signage and branding.

Changing a name also has little impact on enrolment rates or admission scores. A study of 140 American colleges and universities shows that admission rates in the five years following a name change increase incrementally only seven per cent of the time. Furthermore, a study of 522 schools in China shows that eliminating references to historical industrial affiliations has no significant effect on admission scores.

The researchers of both studies concluded with a warning for universities to proceed with extreme caution before altering their branding because erasing a name can invite practical problems. The City of Toronto is currently considering a name change for Dundas Street, its major east-west artery named after politician Henry Dundas, who introduced language in an abolition bill that delayed the end of slavery. The street name change would alter addresses for more than 2,000 business establishments, 7,000 properties and 100,000 residents.

Such a change could just as well plague a university’s student body. Tom Hayes, a marketing professor at Xavier University in Cincinnati and founder of a higher education marketing firm, works with schools who go through name changes. He wrote on marketing.org that boasting the name of a university that no longer exists on a resume can make it hard to make connections in the job market.

These pitfalls are not to say that name changes should always be avoided. In fact, a case study of Missouri State University’s name change (from Southwest Missouri State University) deemed it a success. The researchers offer two pieces of advice to entities considering a branding change: develop a detailed plan, and include any and all groups that may be affected by the name change in the consultation process.

McGill University offers an example of this process as it works to rename their men’s varsity teams, formerly known as the Redmen. The university created a nominations-based panel of 10 athletes, coaches and alumni in 2019. The panel shared its preliminary suggestions for a new name with focus groups and external consultants to evaluate whether they reflect the university’s values of diversity, equity and inclusivity. Following that vetting process, the panel sent the remaining top names to a secondary panel of administrators so they can select a winning name by the fall of 2020.

The result? No announcement yet. Because change takes time, and hasty change often leads to mistakes. So, as we consider scrubbing Ryerson off our buildings, we must carefully think through two matters. The first is whether or not our namesake, for his entire legacy, should be dishonoured. The second is whether or not a name change is what is best for the university and for the people who attend it.

A previous version of this story incorrectly stated that pressure has been placed on the university to remove the statue and change the name since 2017. Ryersonian reporting shows it goes back to at least 2015. We regret the error. We have also updated language in this piece to better contextualize Henry Dundas’s role in delaying the abolition of slavery.