This story is part of Monumental Challenges, a series looking at Ryerson, reconciliation, and the issues surrounding replacing names and monuments.

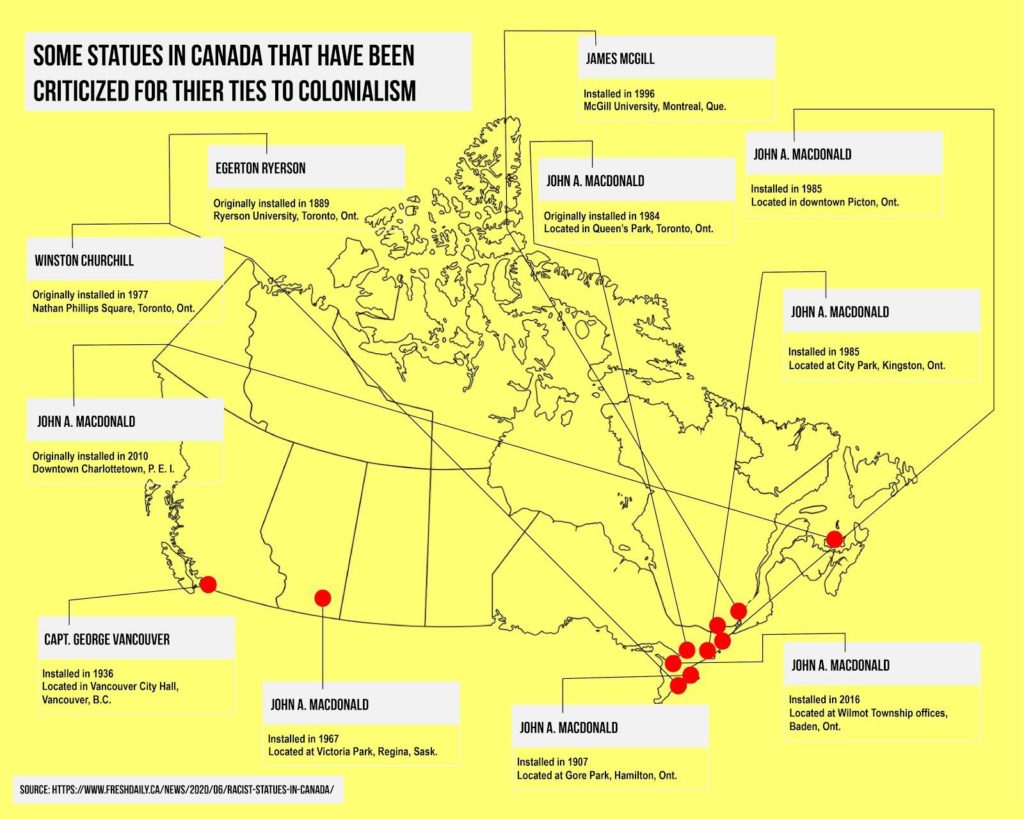

The Egerton Ryerson statue was originally unveiled by Alexander Campbell on May 24, 1889 on the Toronto Normal School Grounds. He was being honoured for founding the Ontario School System, according to the Ryerson Memorial Volume of 1889.

More recently, the same statue was painted on by Black Lives Matter – Toronto (BLM-TO) protesters with the words, “Tear down monuments that represent slavery, colonialism and violence,” on the front.

The plaque beneath the statue states that Ryerson played an instrumental role in the implementation of residential schools in Canada where Indigenous children were subjected to a “cultural genocide.”

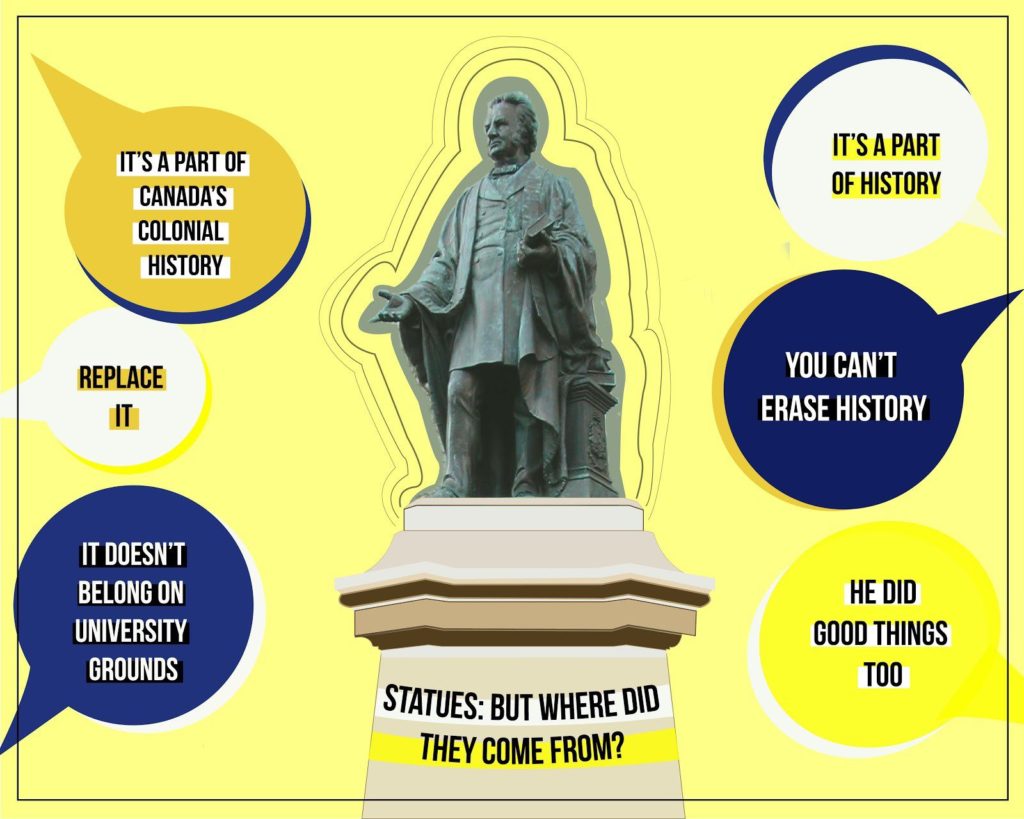

The statue being painted on is not an isolated incident. It comes following recent conversations about whether certain statues with colonial legacies should still exist publicly.

“Something that fascinates me about statues and memorials, in general, is that they seem to always be a kind of flashpoint for public disagreement and debate,” says Sarah Henstra, an associate professor for the department of English.

Among the conversations about what should be done with these statues, there are still questions that have yet to be addressed: where did statues come from and why have they been chosen as a way to mark certain events or people throughout history?

The first statues

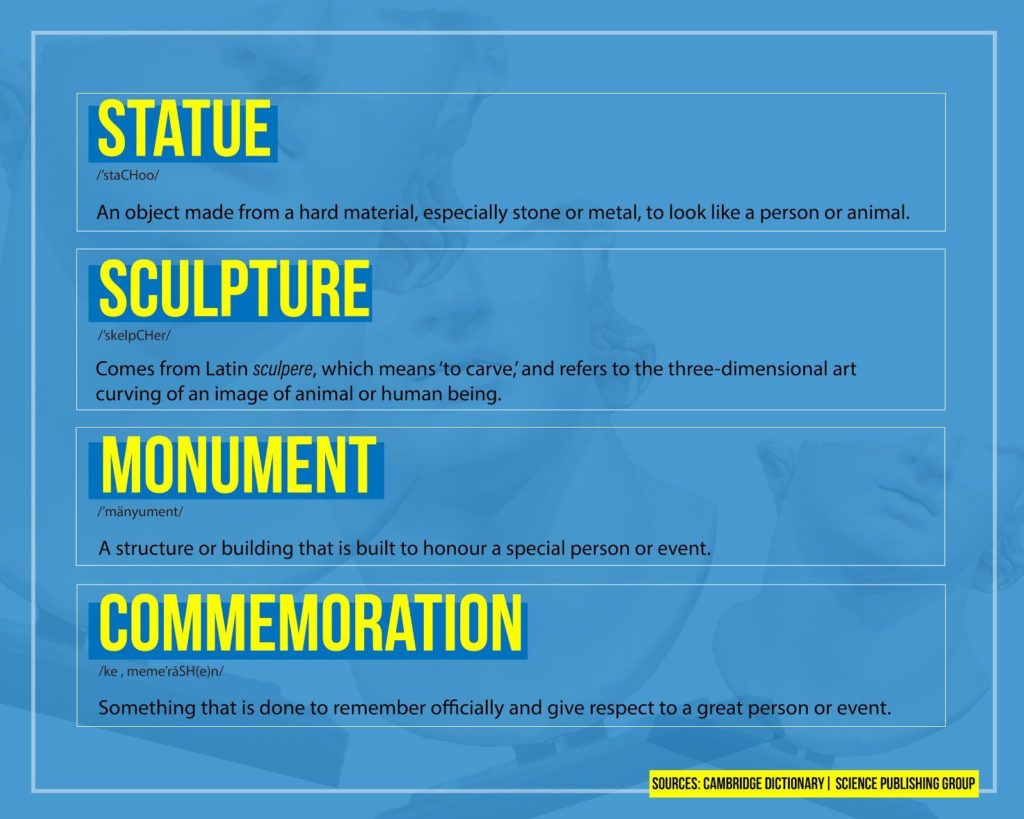

The word statue comes from the Latin statua, which refers to the idea of image or status.

According to Mulualem Daba Tola, in his article titled “The Historiography and Values of Statue Construction: Focus on Global Perspectives,” there were three periods in history that can be used to describe how statues were first used.

In the Antiquity and Middle Ages period, statues were initially introduced in human or animal form for worship and spirituality. Egyptian art revealed that some of the first statues were made to serve as a home for a spirit or god, according to the Ancient History Encyclopedia.

It was during the Modern Era that European states experienced a phenomenon called “stauemania.” During the 19th century, politicians started to use statues as a way to represent ideological ideas about society and spread values of national identity.

Henstra, who has researched public commemoration and monuments, says that statues serve an important function in understanding who we collectively are and who we believe in.

The purpose monuments serve in society

According to Daba Tola, public statues and monuments hold religious, cultural, economic and political values, which is why they still exist. Culturally, they have the power to connect the past generation to the present generation. Many artists create statues with the specific purpose of representing values to which other people in society can relate.

They can also function as a tool, depicting an entire civilization. They become objects of fascination, according to Daba Tola. In 2019, over 4 million people visited the Statue of Liberty in New York.

“There’s a way that monuments look to the future as well as the past … the thing is that, it is a social effort to cement a moment in time and fortify it against the future,” says Henstra.

Politically, there are two ways that statues have been used in public conversations. One is to instill political ideology and legitimize authority, according to Daba Tola. In the Ryerson Memorial Volume of 1889 it is repeated that Egerton’s statue was being erected because of his role in providing free education.

However, he also played a central role in establishing the residential schooling system, which was designed to strip Indigenous children of their identity and caused intergenerational impacts for them and their families. Evidence of his involvement is most prominently seen in his 1846 report on the schools.

Daba Tola says old monuments can also face backlash and be replaced because of the ideological role they play in today’s society.

What comes next?

Many statues across the U.S., Europe, New Zealand and Canada have been taken down, replaced or graffitied because of their ties to colonialism.

“That whole question of moving on as a society is a huge question when it comes to the study and the development of public memorials,” says Henstra. “(Statues) are kind of a double-edged sword.”

When statues are being built, there is open public discourse, but as soon as they are erected authorities tend to shut down all conversations about them, Henstra says. In the case of Egerton Ryerson, a plaque was added to his statue in 2018 to give context about his involvement in residential schools.

Henstra says, “It’s interesting how authorities often think that they don’t need to be answerable to the people who came out on the losing side of these historical events, to the people who are still actively grieving the loss of a particular cultural event or a person.”

RobertAldrich, a professor of European history at the University of Sydney, states in his research article, “Commemorating Colonialism in a Post-Colonial World” that “Debates, emotions, and indeed, the monumental commemorations of empire are all messy and conflicted, perhaps mirroring the uncertainties of a post-colonial (or post-post-colonial) age and mindset.”

Ryerson announced a new task force on Sept. 2, 2020 to examine Egerton Ryerson’s history and legacy, but no firm decision regarding the statue has been made.