Record-high vacancy rates and a provincewide rent freeze create uncertainty for future tenants and homeowners

A number of provincial and municipal measures affecting Toronto tenants are coming into effect over the course of the next year, as renters and landlords continue to adjust to the uncertainty of the COVID-19 pandemic.

This past December, Toronto city council passed a vacant home tax that will come into effect in 2022. The measure is meant to motivate property owners to rent or sell their unoccupied homes by taxing them at one per cent of the assessed value of their home, according to a news release by the city.

The bill passed just two months after the province introduced measures to freeze residential rent this calendar year.

Toronto has experienced record-high vacancy rates during the pandemic. Toronto apartments were at a vacancy rate of 5.7 per cent in the fourth quarter of 2020, compared to 1.1 per cent in 2019, according to an Urbanation report released last week.

Toronto estimates the tax could make $55 to $66 million in revenue. The city’s news release says the money will be used to “fund affordable housing projects.”

“To introduce a vacant home tax at this particular juncture is a little bit strange,” said Omar Ha-Redeye, executive director of Durham Community Legal Clinic & Access to Justice Hub and law professor at Ryerson’s Ted Rogers School of Management. “I think any measure that would improve the affordability of housing for students and for others is a good thing… I just don’t think that everybody is convinced that the vacant home tax is the way to do it.”

Vancouver passed a similar tax in 2017, and that was followed by a provincewide speculative housing tax the following year, aimed at reducing property that is sitting empty because it was bought to be resold at a higher price.

Thomas Davidoff is a professor at the University of British Columbia’s Sauder School of Business. He said that while the number of empty houses in Vancouver before the taxes is unknown, rates of vacancy were low after the taxes were implemented.

Davidoff said this could be due to the fact the scale of speculative housing was overestimated and it wasn’t as large of a problem. It could also be that the tax worked and owners rushed to sell or rent their property before it came into effect.

“The third possibility is there is still a problem and that lots of people are faking it,” Davidoff said. “My guess is it’s a mix of all of those things.”

In November 2020, Vancouver City Council increased the rate of the empty house tax by three per cent. Last week, community advocacy organization Toronto ACORN organized a demonstration in front of city hall calling for a three per cent rate for Toronto’s vacancy tax, according to ACORN Canada. The exact rate and how the tax will be implemented is yet to be determined, according to the city.

Rayman Miller is a Humber College student and Toronto ACORN member who said he became involved with housing advocacy after seeing the negative effects of condo development in his neighbourhood in Weston.

Miller, who came to Toronto from Jamaica when he was three years old and was raised by his single mother, said the tax coming into effect in 2022 is not soon enough.

“I still see [the tax] as beneficial, but I want it to be sped up … because of what’s going on right now with the pandemic,” Miller said.

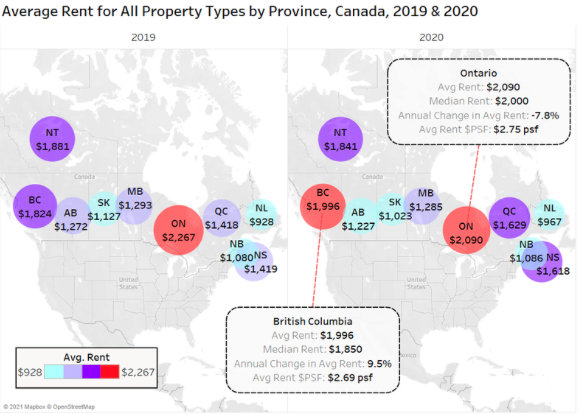

The price of rent dropped 20 per cent in Toronto last year, with the average cost of a one-bedroom apartment dropping to $1,832, according to this month’s rentals.ca report.

Caryma Sa’d, a Toronto-based landlord and tenant lawyer, said she’s cautiously optimistic about the vacancy tax if it’s part of a larger policy initiative. She said she believes the province’s rent freeze is a “nominal measure at best.”

Ontario passed legislation to freeze rent at 2020 levels from Jan. 1, 2021 to Dec. 31 2021, with an exemption for landlords to increase rent to cover major property expenses, like maintenance or repairs.

While the expenses have to be approved by Ontario’s Landlord and Tenant Board, Sa’d said sometimes expenses are more cosmetic than essential. Renovations like redoing a balcony or lobby means people’s rent could still increase even with the freeze. With the current measures set to expire in December, there’s nothing to stop rent from increasing in 2022.

The Landlord and Tenant Board is also continuing to operate and hear eviction applications while the province halted the enforcement of residential evictions during stay-at-home orders.

Sa’d said this means that while people cannot be forced to leave their home now, landlords can still serve eviction notices that could be enforced in rapid succession when restrictions are lifted.

“I would expect a period of conflict after this ban is lifted,” Sa’d said. “As we saw in August, that eviction ban was lifted even though the pandemic obviously wasn’t over.”

Ha-Redeye said that because of the enormous backlog and confusion in hearings from the last eviction ban, “the last thing in the world that you want at this point in time… is to have your tenancy dragged before the Landlord and Tenant Board.”

Ha-Redeye added that both the vacancy tax and the rent freeze are not long-term solutions because of the exemptions and ways property owners can get around them. He said measures instead need to challenge the assumption that building more will bring prices down.

“We have to reimagine how we’re doing things,” he said, “[and] really have to look at housing in a different way. It’s not simply a matter of increasing the surplus.”