Ryerson has turned to automated assessment tools like Respondus LockDown Browser and Monitor to prevent cheating. But is virtual proctoring software truly worth the cost?

Rayyan Akhtar hasn’t experienced a normal university exam yet — but he has a good idea of what it shouldn’t feel like.

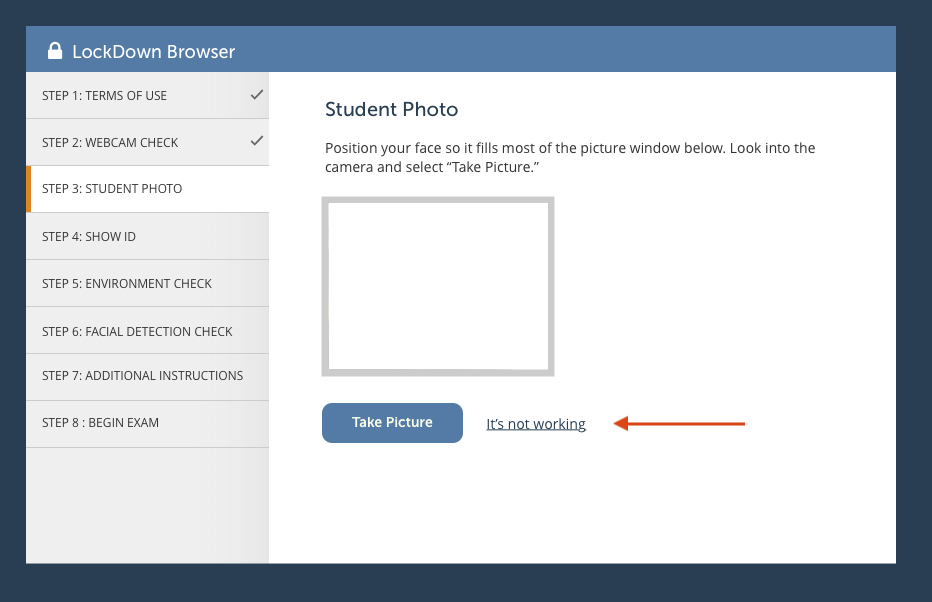

The first-year Ryerson University business management student writes all of his exams from a computer niche in his home. Every so often, during a typical test, Akhtar will get lost in a tough math problem and dip his head down to solve it in his notebook. This triggers a pop-up notification that orders him to bring his head back into the frame. When Akhtar catches sight of it, he feels a jolt of panic and loses focus.

“I’m thinking, man, is this going to invalidate my exam? Am I going to get charged with academic misconduct?”

Ryerson argues this software helps to prevent cheating and ensures academic integrity. Some students, however, find it acutely anxiety-inducing during an already difficult period.

Since the COVID-19 pandemic reached Canada in mid-March, nearly all Ryerson courses and exams have been delivered online. In an effort to mitigate cheating during virtual tests, the school has turned to Respondus’s automated proctoring technology. According to the U.S.-based e-learning company, its Respondus Monitor software is employed by over 1,000 higher learning institutions, who will use it to proctor over 20 million exams this year. Its LockDown Browser tech is even more popular, despite its 1.3 star (out of five) rating on the App Store.

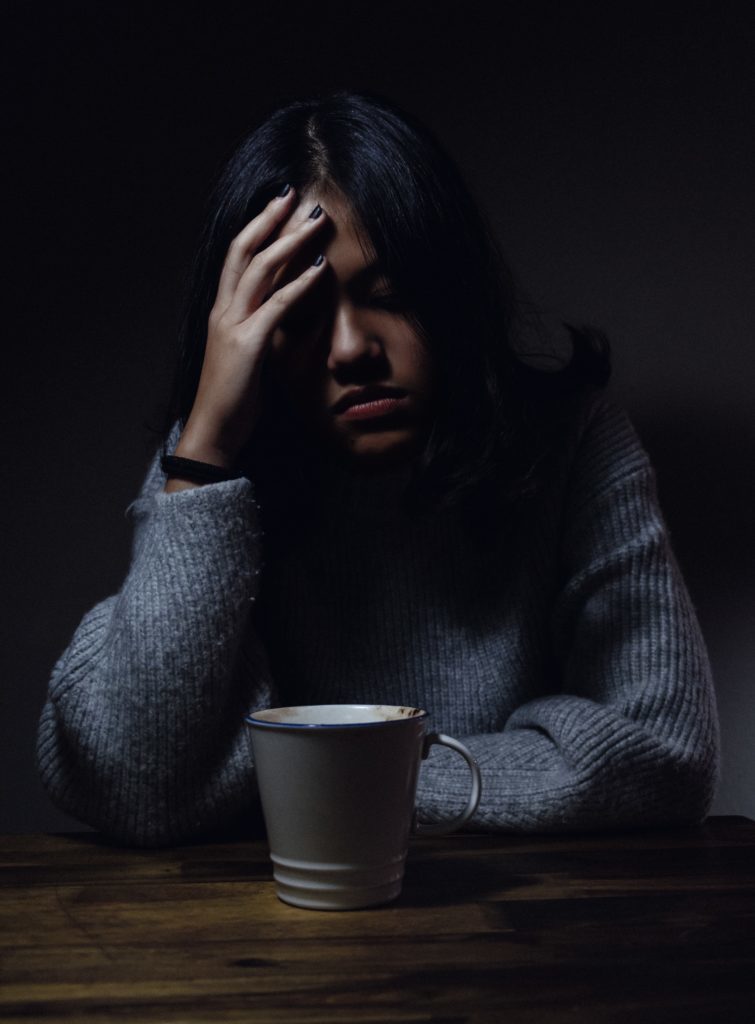

The sudden shift to online learning has been tough for a lot of university students. Almost two-thirds of Canadian students say it has negatively impacted the quality of their education, due in part to a lack of interaction and engagement with professors. Student mental health has also deteriorated amid the pandemic. A recent Toronto Star investigation found that COVID-19 increased depression levels among Canadian post-secondary students by 35 per cent.

Akhtar thinks the company’s “invasive” software has been “an additional unnecessary stressor in a time where university students across the globe have already been cut a horrible deal.”

Other students are also wary of Respondus’s system.

“The proctoring system is just really stressful,” said Kennedy Byron, a second-year social work student who has used Respondus for two exams so far this year. “I’m typing on my laptop and the little thing would come up like ‘bring your eyes up to the screen again or don’t look away.’ It’s just anxiety-inducing… it’s always watching you, and you don’t really know who’s watching.”

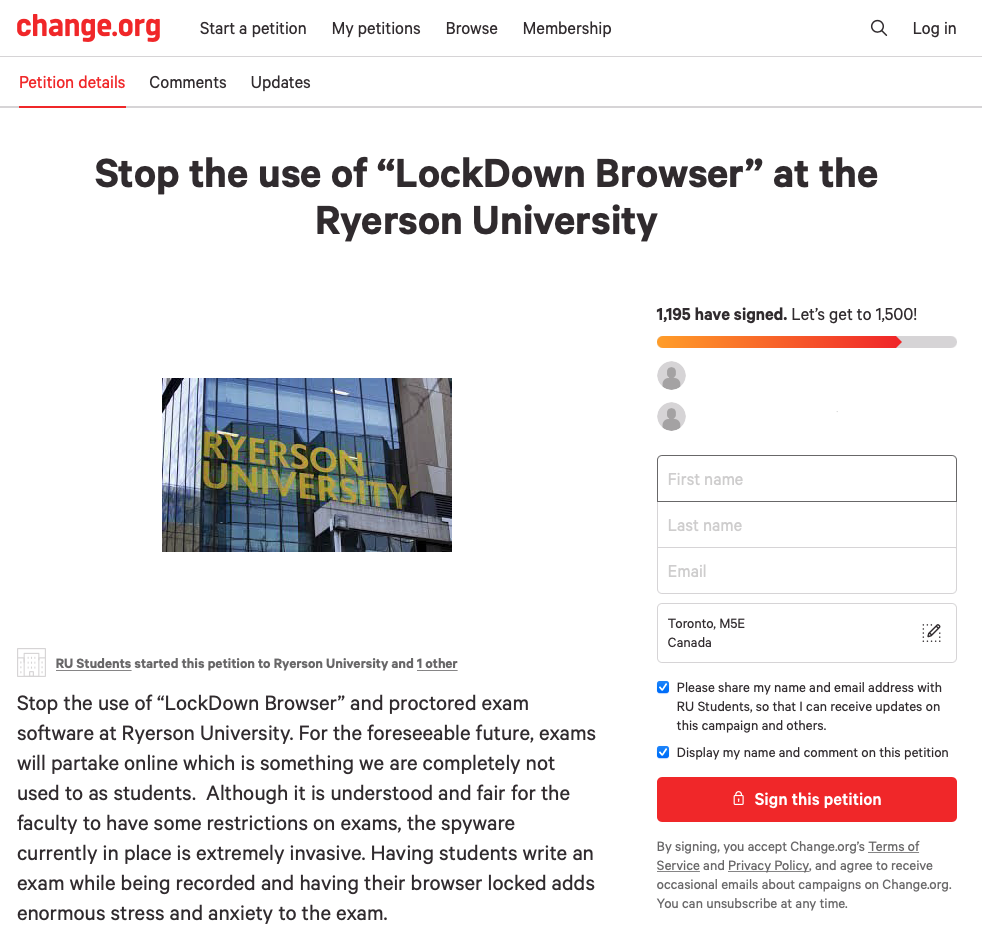

Students demand Ryerson ban Respondus

A recent Change.org petition calling for Ryerson to stop the use of LockDown Browser during exams has garnered 1,195 signatures as of Nov. 26. Created by “RU Students,” the petition refers to Respondus’s proctoring tech as “invasive spyware,” and argues that taking a test “while being recorded and having (your) browser locked adds enormous stress and anxiety to the exam.”

Student bodies at several other Canadian universities have also voiced similar concerns. The University of Manitoba’s student union board of directors voted unanimously to oppose the use of Respondus Monitor at their school after students raised issues about personal privacy, accessibility for students with disabilities and the risk of false positives. At the University of Ottawa, in response to the implementation of Respondus Monitor, a petition to “stop using harmful proctoring software” has received nearly 2,700 signatures.

Ryerson University president Mohamed Lachemi told the Ryersonian it was important for Ryerson to offer its instructors a means of automated virtual proctoring for online exams, adding that he views software like Respondus LockDown Browser and Monitor as a deterrent to some forms of academic misconduct.

Lachemi said he is aware of the petition and student concerns regarding the use of Respondus’s tech, but did not specify how the school might address them, instead deferring to Ryerson’s existing policies.

“It has been our aim to ensure that faculty and instructors engage in the most appropriate usage of this software,” said Lachemi, stressing that faculty and instructors “are being strongly encouraged to find alternative forms of assessment and to adopt automated virtual proctoring only if absolutely necessary.”

The shift to online exams has impacted students in a range of ways

For Samantha Tome, the adjustment to online exam-taking has been difficult. The fifth-year biomedical sciences student is the group mentoring lead for Students with Disabilities, a student support group at Ryerson.

As a student with an anxiety disorder, Tome is registered with Ryerson’s Academic Accommodation Support. Prior to the pandemic, she would write her tests in a small, quiet room in the basement of the Victoria Building. This arrangement helped ease her test anxiety. Today, she writes all of her exams from home, where it’s tougher to achieve the same level of peace.

“There is often noise that I cannot control, such as my dog suddenly barking, or my home phone suddenly ringing,” she said. “Distractions are everywhere, no matter what room I go into.”

“As someone who already struggles with horrible test anxiety, having this software would be a detriment to my education,” said Samantha Tome, a fifth-year Ryerson biomedical sciences student.

Although she hasn’t personally encountered Respondus’s software, Tome opposes its use, calling it “anxiety-inducing in a time when there should be more leniency and understanding,” in a comment she left on the Change.org petition.

“As someone who already struggles with horrible test anxiety, having this software would be a detriment to my education,” said Tome, who thinks the associated stress would decrease her academic performance and negatively impact her mental health.

Does automated proctoring software actually prevent cheating?

While students find proctoring software anxiety-inducing, some evidence suggests that it’s effective in upholding academic integrity. According to a 2017 study from Miami University, students whose tests were proctored with video monitoring scored on average 17 points lower than students who took the same tests with no proctoring. The researchers concluded that such a discrepancy might be due to the fact that video monitoring deters cheating.

The Washington Post reported that the failure of universities to pay for adequate proctoring services has led to increased levels of cheating during the pandemic. But other studies indicate that even in the presence of such software, three out of four students say it’s easier to cheat during an online test than an in-person test.

Most proctoring systems also have limitations. For example, they might not be able to identify if students have a second computer present, which could allow them to search the internet for answers.

In 2020, exam proctoring service company ProctorU reported less than one per cent of 340,000 in-person test takers cheated between January and March. The company later reported that over the course of the following three months — when universities were forced to begin administering tests virtually — eight per cent of 1.3 million test takers cheated.

Byron thinks a student who is creative and willing to break the rules could easily outsmart a proctoring system and cheat.

“Students could discuss with people on the sidelines (while taking an online test),” she said.

Mitigating cheating probably has less to do with strict surveillance, Byron said, and more to do with the type of test administered, because the qualitative nature of her exams does a better job of discouraging her from copying answers than a proctoring system.

“We don’t have ‘what is question A and what is question B (on our exams).’ It’s more essays,” she said.

Faculty and instructors should strive to “reduce the need for high-stakes exams and tests,” said members of Ryerson’s Centre for Excellence in Learning (CELT) and Teaching and the Academic Integrity Office (AIO) — responsible for the school’s transition to online learning — in an email to the Ryersonian.

Ryerson gives its instructors the discretion to decide whether the use of Respondus’s software is warranted. To ensure academic integrity during online exams, the group recommends that Ryerson instructors use “the simplest option that makes sense for their course,” adopt technology that is well-known to both students and themselves, and apply automated virtual proctoring “only if deemed absolutely necessary for assessment.”

Neither CELT nor the AIO would comment on how online exams or the use of this software has affected the rate of academic misconduct since they don’t have “all the information.”

How equitable is this tech?

Akhtar said he is privileged to be able to pursue his education from home “without being that adversely affected by the pandemic,” but expressed concern for how this sort of proctoring software might impact students whose learning has been more directly affected by COVID-19.

“It’s just another layer of stress that is not needed at a time like this,” he said.

The petition mentions the “huge toll” the download-required software takes on device hardware and performance, and highlights that it requires a “quiet, secluded workspace,” a “good, stable Wi-Fi connection,” and a working webcam and microphone, which not all students have the ability to access for a variety of reasons.

“This one-size-fits-all approach to ensure academic integrity puts students who might already be struggling financially during a pandemic at a disadvantage,” said Rayyan Akhtar, a first-year Ryerson business management student.

Akhtar referred to its use as “inherently classist.”

“Ryerson assumes that all its students have adequate access to technology, stable internet connections and quiet spaces to work,” said Akhtar, even though students come from a wide range of socio-economic backgrounds and, as a result, many lack these requirements.

“This one-size-fits-all approach to ensure academic integrity puts students who might already be struggling financially during a pandemic at a disadvantage.”

CELT and the AIO told the Ryersonian that the university has made efforts to address these issues and better facilitate the transition to virtual testing. The university cited its purchase of approximately 400 laptops for students in need and the continued availability of Academic Accommodation Support for those who require alternative test-taking arrangements.

“If access to required technology is a concern, students are encouraged to raise this with their instructors as soon as possible,” they stated.

In response to a question concerning what the university’s policy is when a student loses their internet connection during an online exam, they advised students to “contact their professors directly.”

Confidence in academic integrity might decrease pressure to cheat

In situations where formal examinations are required, a rigorous software that threatens to catch cheaters could have benefits.

“When students feel confident their classmates cannot easily cheat, they don’t feel the pressure to cheat themselves,” Jodi Feeney, Respondus’s chief operating officer, told the Ryersonian.

When asked, Feeney acknowledged student concerns surrounding the use of her company’s software. “We don’t want to diminish the stress everyone is experiencing as a result of this pandemic.”

But she also highlighted that exams have always “included an element of stress, regardless of the testing environment,” citing the stress associated with a professor walking around the classroom during an in-person exam.

“Most people agree — even students — that the only way to ensure the integrity of an online exam is to have some type of proctoring.”

Prior to the pandemic, when students were given the option of either using Respondus’ services or visiting an in-person test centre, Feeney said 98 per cent opted to use automated proctoring, putting the convenience of an online exam first.

“It was viewed as being more convenient than going to a testing centre,” she said.

Feeney claimed that “any decent proctoring solution will reduce cheating to roughly five to 10 per cent of examinees through deterrence alone.”

CELT and the AIO told the Ryersonian that they did not have enough information to determine whether cheating rates at Ryerson have changed since moving to online classes or adopting proctoring software.

Data privacy and security concerns

When taking a test with Respondus, it can be difficult to shake the sensation that you’re being watched. Given rising public awareness about the often questionable collection and storage of personal data by tech companies, some students wonder how their information is being used and stored.

“Apart from my prof, I have no idea who else has access to this information or the reputability of Respondus as a company for data security,” said Akhtar. “How long will the recordings of myself and photos of my ID be stored? Can Ryerson guarantee that my information is safe and won’t be sold for profit by Respondus?”

Feeney directed the Ryersonian to a document that summarizes the company’s practices regarding data privacy and security, and cited the support it has gained from universities because of them. The document claims that the company doesn’t sell or share student data.

“Over 1,100 universities have selected Respondus Monitor as their automated proctoring system — many after conducting detailed reviews of our security and privacy policies,” she said.

Feeney told the Ryersonian that the company’s system is fully automated, “so there isn’t a human watching the student during the exam.”

“We don’t drop in, we don’t review the video after — people think we’re doing that and we’re not,” said Respondus’s CEO David Smetters.

Respondus records exam sessions and, afterwards, only the student’s instructor has access to the proctoring information and video, said Feeney. She added that the company’s AI doesn’t measure the occurrence of cheating, nor indicate that it has taken place. Instead, it identifies anomalies in student behaviour, generates a report summarizing these findings, and shares this report with the student’s instructor, alongside the video and audio recordings for reference. Respondus then leaves it up to the professor to review said materials and “decide whether an examination rule has been violated.”

“We don’t drop in, we don’t review the video after — people think we’re doing that and we’re not,” Respondus’s CEO David Smetters told The New York Times.

According to the terms of use for Respondus Monitor, the company only reviews or analyzes exam session recordings when directed to do so by educational institutions, or to “resolve technical problems, improve system performance, modify its software or investigate violations of its terms of use.”

The privacy policy for Respondus Monitor states that the company retains students’ data for up to five years. By downloading the application and agreeing to its terms of use, students authorize Respondus to share video or audio exam session recordings with contracted third-party researchers, including “research institutions and/or biometric experts.” According to these terms, these researchers are bound by confidentiality agreements, and the company does not provide them with any “personally identifiable information … such as the student’s name, course name, institution, grades or student identification photos.”

According to Ryerson’s agreements with Respondus, Ryerson owns and controls its students’ proctoring data, and the school has “an institutionally endorsed agreement with Respondus that confirms information technology security and privacy.”

Feeney cited live proctoring via web conferencing as a potential alternative to the use of her company’s software. However, Ryerson recommends against this practice due to privacy concerns. “There is no way to ensure student privacy with Zoom,” wrote the school. Live proctoring through Zoom or another similar platform would require students to turn on their webcams, enabling them “to see everyone else and their surroundings,” including during the identification verification process, posing a privacy risk to students.

Alternative methods of testing

Some instructors have found ways to administer exams while doing away with proctoring systems altogether.

This semester, Laurel Walzak, an assistant professor at the RTA School of Media who teaches a 200-level sport marketing course, chose to allow her 82 students to collaborate in groups for their final exam. She tested the approach during a recent midterm and saw no evidence of cheating.

“I told them they could talk amongst each other… because I didn’t want them to have the feeling of, ‘if I didn’t understand the question and I speak to a friend, am I cheating?’ so I just took that element away.”

Walzak said she plans to steer clear of multiple choice and true-or-false exams this December.

“I wanted to take away the temptation to cheat, though I think the temptation is very low. What I gave them was a problem, a real-life problem that they would have to take the knowledge from this course to solve.”

Looking forward

Ultimately, no solid timeline exists for a return to in-person classes and exams at Ryerson, an institution nestled inside one of Canada’s hottest COVID-19 zones.

Ryerson has no current plans to stop using Respondus’s software to help deter cheating. In instances where it is deemed necessary by professors, students will simply have to trust that Respondus and Ryerson are respecting their privacy and taking care of their personal data. In turn, flexibility by professors could limit the need for this software.

Despite students’ concerns, Ryerson has no current plans to stop using Respondus’s software.

Adopting more qualitative testing methods, as Walzak did, is one possible alternative for professors that could both ensure academic integrity and demonstrate greater understanding for their students.

But in light of the unique circumstances surrounding COVID-19, Tome said she thinks the university should ban the proctoring software altogether, and instead make alternate exam proctoring arrangements.

“I think I can speak for many students when I say it is unfair to treat our tests and this school year in general like a normal test or school year, because it’s not one. And we should therefore make accommodations … in order to ensure not only the success of our students but also to maintain their mental health.”