Listen to the story here:

When Mike Munn became fascinated with filmmaking at age eight, he never imagined his work would secure an Academy Award nomination one day. Decades later, Munn has taken home the Canadian Screen Award for Best Editing in a Documentary for Nisha Pahuja’s To Kill a Tiger, earning an Academy Award nomination as well.

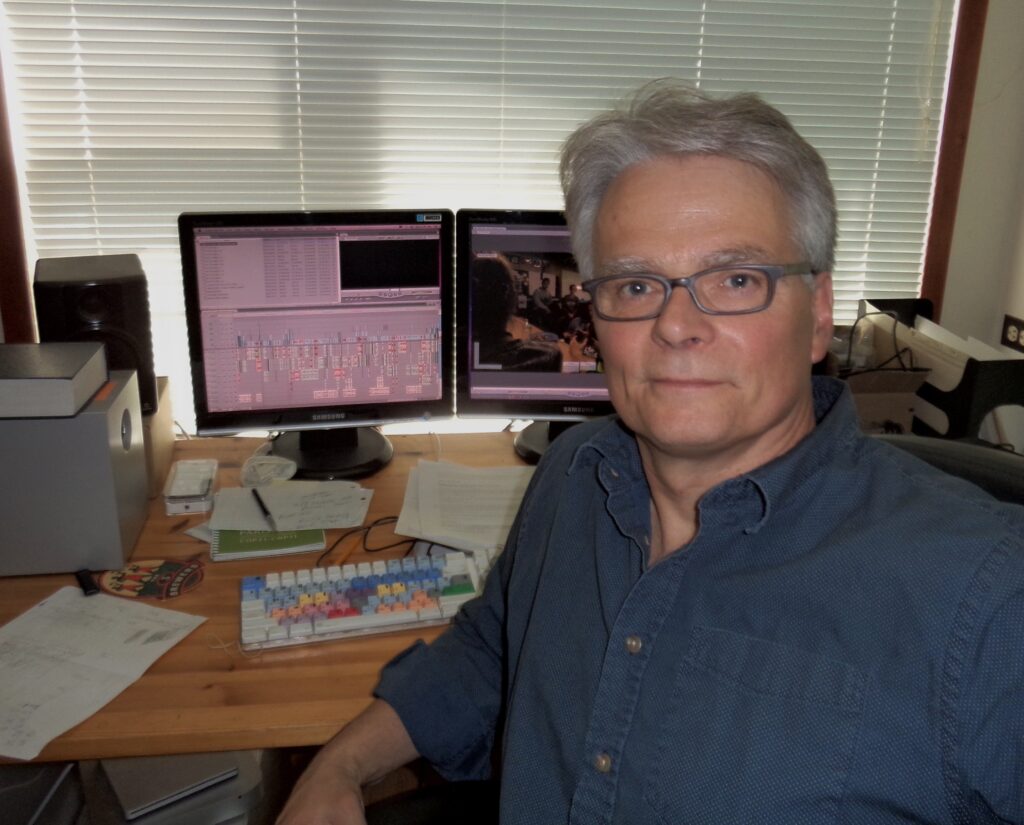

We caught up with the Toronto Metropolitan University (TMU) film and photography graduate to discuss his insights, experiences and advice in the realm of film editing, taking a deeper look into the creative process shaping narratives like To Kill a Tiger.

OTR: How was your experience and process of working on To Kill a Tiger?

Mike Munn: It was great. It was a little unusual in that another great editor, Dave Kazala, started the project and it was about three years of editing in its entirety. The whole process took about eight years. Nisha developed, filmed and shot for three years and then the editing process took about three years. Dave worked the first year and then I took it over from assembly to the final stage.

The main thing about the film that was unusual is that Nisha had originally wanted to make a bigger, wider film studying masculinity and structures of patriarchy in Indian culture. The story of To Kill a Tiger was just one of three stories that she was following while shooting. The first six to eight months of my work on the film, I was trying to make the whole thing. I was trying to tell the To Kill a Tiger story inside this other, bigger story and it was quite difficult and complex because we were working with somewhere between 1,000 and 1,300 hours of footage.

But at a certain point, we realized that To Kill a Tiger was the story the film should be about. That’s the first time that’s ever happened [to me] and the process of changing that was quite intense and complex but we got there in the end.

You recently won the Canadian Screen Award for Best Editing in a Documentary for your work on To Kill a Tiger, how does it feel to be recognized on a global stage?

Yeah, it’s great. It’s certainly an unusual feeling because it doesn’t happen that often. Previously, I’d done a film called Stories We Tell with Sarah Polley and that was lucky enough to go viral around the world as well so I’d had a bit of experience with that. But when you primarily work on your own with maybe one other person, for sometimes years on something, and there’s some recognition when it goes out into the world, it’s great. And then before you know it, you’re just back in the editing room, working on something else. But yeah, it’s fantastic for sure. It’s great for the film but it’s also great for the impact campaign that Nisha is working on and the issues and themes of the film. Hopefully, it’s going to result in at least some incremental changes in people’s lives.

How have your education and experiences at TMU contributed to your career in film editing?

TMU or Ryerson [University] at the time, was really known in Toronto, and probably in Canada, for being a very practical course. They had lots of equipment; camera equipment, sound equipment, and they also had a soundstage, a shooting soundstage and a mixing theatre where you could mix your sound. That was something a lot of other schools didn’t have. You could actually go to Ryerson and make a film.

The film industry is not an industry that looks at your education. I don’t know if anybody’s ever asked me to see my degree; it’s like a trade. You go in and you kind of apprentice almost with people or you just start doing it and as soon as you get one credit, that leads to another credit and you actually build your resume that way. I think the practicality of the film program was the reason that I was well-prepared to get into the industry afterwards.

What role do you believe editing plays in storytelling and why is it important?

It’s interesting because I’ve done quite a lot of scripted work, you know, fictional filmmaking which requires a script and I’ve also done quite a lot of documentary, so I think I’m a little uncommon in my editing career because I’ve worked in both fields. I think editing in both the scripted and the documentary, you’re storytelling.

The main difference is that the scripted film has a script and the narrative heavy lifting has already been done, the story is there. In documentary [work], there is no script. There’s no beginning, middle and end. You may have 300 hours of footage or you may have 1,500 hours of footage, but that’s just a bunch of footage. There’s the story that wants to be told but you have to find out the structure and you have to work with the filmmaker to do that.

Those are the two differences and they’re both rewarding in their own way. I love working with actors and performances and shaping performances into character but I also like being in the guts of the story or being a co-collaborator in creating the story. As an editor, you’re really kind of the guardian of the story.

What skills or qualities do you believe are crucial for a successful career in film editing?

I think the strongest one is patience. I think you need to work with somebody who is methodical and patient and not in too much of a hurry. Especially with documentary editing, there’s no kind of instant gratification when you start off and you’ve got 1,000 hours of footage. It can be several months before you actually see progress. So, patience is a big one and just being thorough and [paying] attention to detail. If you’re not precise and thorough and rigorous at the beginning of the process, in just the organization, the project can kind of fall apart.

And diplomacy, being a diplomat. You’re working with various filmmakers and everybody has a different personality, part of your role as an editor is to tap into what it is they want to do and tap into their sensibility. Often, the editing process for every filmmaker is a really sensitive time because they’ve shot the film and it’s not necessarily the film they thought they were going to make. It changes, every film changes through writing, shooting and editing.

Someone once said films are written three times; it’s written when you write it, it’s written when you shoot it and it’s written when you edit it. It changes, and so given that, it is an intimate process, it’s usually only you and the filmmaker. You have to be supportive and a cheerleader and you have to lift them up, encourage them and assure them that we’re gonna get there. It’s such an intimate process, it’s just a couple of people in a room, having conversations for months and months and months. That’s part of what always attracted me to it. I always appreciated the time and the ability to talk and discuss and work through things, it’s like making a big puzzle together.

What advice would you give to current students aspiring to pursue a career in film editing?

Everybody has different means to be able to support themselves but if you can, get a gig within the film industry or say you’re in the editing field, get in as a second assistant or first assistant editor on something, no matter what it is. You have to make a living and you have to make money but I also think if you can get a chance to actually edit something, whether it’s for a friend or somebody you know who’s doing a short film, if you can, just edit and work on things, because every experience will lead to another experience.

If you do a short film or a couple of short films, you might hear from somebody. Maybe they’re going to do a feature or maybe they know somebody that’s going to do a feature. It’s kind of weird how it works, when you put yourself in that position, one thing can lead to the next and at a certain point, you’ll find that the ball is starting to roll. Just be hands-on, get good at what you can and build a portfolio of things you’ve actually done.

This interview has been condensed and edited for clarity

Reporter, On The Record, Winter 2024.